Avatar of the Russian avant-garde: 5 key works by Konstantin Melnikov

Melnikov house. Source: PhotoXPress

Russian architect Konstantin Melnikov, one of the outstanding figures of the Soviet avant-garde movement, was born 125 years ago on Aug. 3. Melnikov lived a long life, but his most active planning and construction took place over the space of just 10 years, from the mid-1920s to the mid-1930s – a startlingly prolific period in which no fewer than 27 buildings he designed were constructed (16 of which have survived to the present day), with more than 70 remaining blueprints.

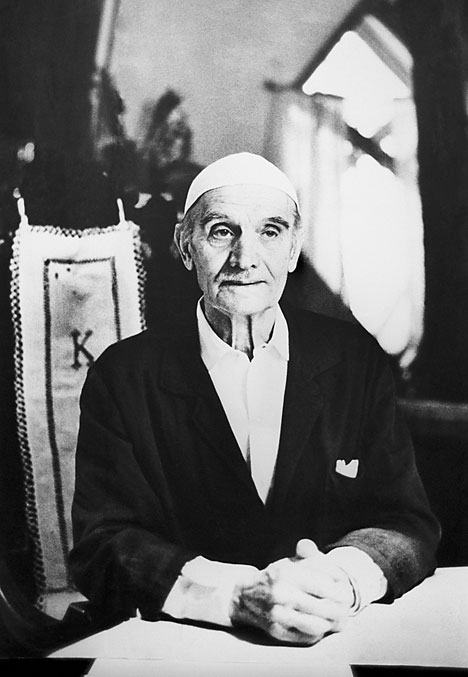

Konstantin Melnikov, 1970. Source: TASS

Although his works are usually considered to belong to the constructivist school, the architect himself pointed out that he did not work in any particular style and that each project had to be completely unlike any previous one, otherwise there was no sense in it.

Bus Garage at the Bakhmetevsky Bus Park (19a Obraztsova Street), 1926-27

Melnikov's first construction was a wooden pavilion called Makhorka at the All-Russian Agricultural and Handicraft Industry Exposition in 1923 in Moscow (it did not survive). The original form of the pavilion, with its external spiral staircase, glazing and large flat planes for advertising posters, had a great influence on all of the Soviet avant-garde.

Two years later the 35-year-old architect obtained global fame: The USSR pavilion that he built for the Decorative and Applied Arts International Exposition in Paris in 1925 eclipsed even Le Corbusier's “Pavilion de l'Esprit Nouveau.”

The building of the Garage Center for Contemporary Culture houses the Jewish Museum and Center of Tolerance. Source: Sergei Fadeichev/TASS

This was the beginning of Melnikov's own Golden Age. In Paris, Melnikov was commissioned with two garages, one of which, a very original structure, was to have several levels and be placed on a bridge over the Seine. Having returned from Paris, he perfected his technique and built two garages in Moscow: the Bakhmetevsky Garage, which was destined for buses (today it houses the Jewish Museum), and another one for trucks.

The novelty of both constructions consisted of the fact that entering and exiting the facility could be done through different gates without driving in reverse. The Bakhmetevsky Garage also has the form of a parallelogram whose ledges are highlighted by the bus stands.

The Rusakov Municipal Workers' Club (6 Strokynka Street), 1927-29

In the second half of the 1920s, clubs for workers’ “cultural recreation” became very popular. In 1927-28 Melnikov drafted seven projects for such clubs, five of which were realized. In each he concentrated on the external expressiveness of the building's composition and on the rational use of internal space.

The Rusakov Club. Source: Sergei Fadeichev/TASS

The Rusakov Club has three balconies extending from the amphitheater of the auditorium to hang over the external façade. The moveable partitions can be used as a part of the hall or as separate auditoriums.

In that period theaters were no longer built with balconies and boxes since Soviet society was not divided into rich and poor and therefore space had to be indivisible. But Melnikov compensates for this simplification. Even though this technique initially received much criticism, it was later actively used in construction, particularly in the municipal pool in Wuppertal, Germany and in the Wiener Stadthalle (Viennese City Hall).

The Burevestnik Shoe Factory Club (17 Third Rybinskaya Street), 1928-30

There are no identical projects among Melnikov's clubs – their individuality was more important for him than their typology. His projects stood alone in the USSR and all the other structures, in comparison, seemed like a variation on one idea.

Burevestnik Factory club, 17/1 3rd Rybinskaya Street, Sokolniki, Moscow. Source: Yury Artamonov / RIA Novosti

It is important to note that his novelties outraged constructors but were favorably received by the clients – everyone wanted original solutions.

The Burevestnik Club consists of a rectangular structure housing an auditorium built on a long and narrow plot of land. But the main attraction is the 5-petaled glass tower with its small activity area.

The K. S. Melnikov Residential Building (10 Krivoarbatsky Lane), 1927-29

This one-apartment building is one of the most original works of the Soviet avant-garde, representing not only the creator's style but more his architectural thinking. Built and self-financed by Melnikov for himself and his family at the height of his career, it essentially became the last private house in a country that had done away with private property.

Source: Segei Mikheev / RG

Two cylinders with equal diameters but different heights are "wedged" into each other, forming a figure of eight if looked at from above. For experiment's sake Melnikov left a big window-screen in one of the cylinders and in the other created many small rhombus-shaped windows, which were achieved thanks to the shifting of the brickwork. In this way two rooms (the study and the workshop) are formed, identical in form and size, the perception and atmosphere of which are radically different due to the play of light.

The Gosplan Garage (63 Aviamotornaya Street), 1934-36

One of the master's final structures was at least half a century ahead of its time in its architectural boldness: the massive body of workshops is vertically cut by flutes while the garage itself with its circular window looks like an enormous bathyscaphe.

This building in Aviamomornaya Street was built in 1936 for the State Planning Committee, Gosplan, by eminent architect Konstantin Melnikov. Today it is known as the Garage of Gosplan. Source: Ruslan Krivobok / RIA Novosti

In 1933 Melnikov, along with 12 leading international avant-garde architects (including Auguste Perret and Le Corbusier), was invited to organize a personal exhibition at the Milan Triennale, which crowned the Russian architect as one of the major influences in the history of world architecture.

But in the USSR, which was gradually adopting the Stalinist Empire style, his ideas had no place. By 1938 he was completely estranged from architectural work. It could have been worse, but the glass sarcophagus that he designed for Lenin's body in 1924 (which was used up to WWII) saved him from repressions. Melnikov spent the last 36 years of his life as a recluse, teaching and writing his memoirs.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox