Dancing their way to freedom: 4 great Soviet ballet defectors

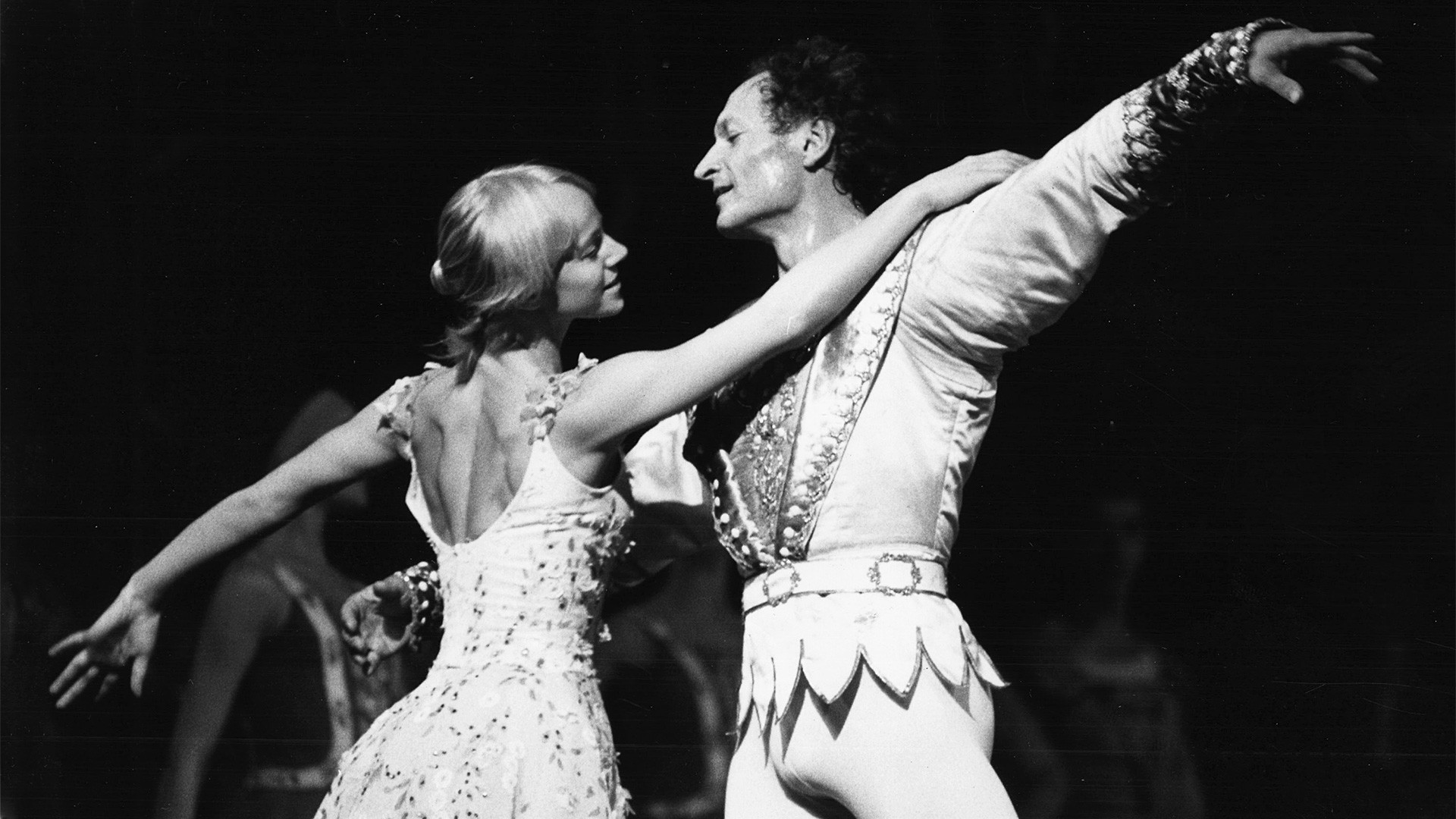

Russian dancers Galina Panova and her husband Valery Panov are pictured during rehearsal with the Berlin Opera Ballet Production of "Cinderella" at the New York State Theater of the Lincoln Center for the performing arts, July 6, 1978.

APValery Panov

Russian dancers Galina Panova and her husband Valery Panov are pictured during rehearsal with the Berlin Opera Ballet Production of "Cinderella" at the New York State Theater of the Lincoln Center for the performing arts, July 6, 1978. Source: AP

By the time of his emigration in 1974, Panov, aged 36 at the time, had been dancing for many years for Leningrad’s Kirov Ballet (now the Mariinsky Theater in St. Petersburg) and had starred in film adaptations of several ballet performances, including Swan Lake, The Sleeping Beauty and The Blue Bird. Nevertheless, once he started to fight for the right to emigrate to Israel (his real surname was Schulman), he instantly was banned from any performances – the Soviet authorities considered everyone who tried to leave the country for good a public enemy.

Panov had numerous reasons to leave: “I fell from grace – I was not even allowed to go abroad for 13 years after our U.S. tour in 1960... Yes, originally, I traveled quite often. But the authorities have soon concluded I ‘was getting acquainted with new people too easily’ and I was banned from leaving the country [without an exit visa],“ he is quoted as saying by writer Polina Limpert in her book Valery Panov: An “Ambassador” of Israel in the World.

The musical To Dance is based on Panov's eponymous autobiography, published in New York in 1978. Kyra Robinov, the librettist and producer of the show, told RBTH why she had found the dancer's story interesting.

Dancers Valery Panov and Jesse Carrey. Source: Press photo

“I had been familiar with the Panovs’ plight, I was in school in Boston when they first came to this country and I rushed to see them perform. From the moment I saw Valery dance, the fiery intensity that drove this man to defy the daunting Soviet authorities was evident.

“Clearly, not even the KGB could crush his spirit. I was drawn to bring Panov’s story to the stage because of its blend of tragic elements and its beacon of hope. It’s a David and Goliath story that resonates with artists and people everywhere.”

To dance - a passionate new musical. Source: YouTube

After completing his emigration to Israel in 1974, Panov toured the whole world, both as a dancer and as a choreographer. In 1977, he began working as the ballet master of the Deutsche Oper Berlin, later cooperating with numerous European and American companies – he was the artistic director of the Royal Ballet of Flanders and the ballet company of Theater Bonn in Germany. In 1998, the dancer founded the Panov Ballet Theater in the Israeli city of Ashdod.

Mikhail Baryshnikov

Mikhail Baryshnikov carries flowers and wears a City of London sweatshirt during a rehearsal of the American Ballet Theatre's production of "Giselle," in New York, May 27, 1977. Source: AP

Like Valery Panov, renowned choreographer Baryshnikov was a member of the Kirov Ballet before defecting to Canada in 1974 while on tour there.

“I just got the message from my closest friends, that if I have any doubts and if I want to stay, they will help me…” the dancer revealed in an interview with Larry King in 2002.

“They put me together with young Canadian lawyer whom I met and discussed briefly all options. And I asked him to delay decision until – I wanted to finish, this was last performance in Toronto, I danced actually last performance, and after performance I joined him in the hideaway car…”

White Nights, Mikhail Baryshnikov & Gregory Hines. Source: YouTube

Baryshnikov went on to become a real star in the United States – he was the principal dancer with the American Ballet Theater, later becoming the troupe's artistic director and ballet master. He also pursued a successful film acting career. Ten years ago, the dancer founded the Baryshnikov Arts Center in New York.

Mikhail Baryshnikov has never returned to Russia since his defection.

Rudolf Nureyev

Rudolf Nureyev and Karen Kain perform a movement from "Sleeping Beauty" as part of the gala celebration of 100 years of performing arts at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, May 14, 1984. Source: AP

Nureyev was the first Soviet ballet dancer to defect – he stayed behind in Paris in 1961 while on tour with the Kirov Ballet. The troupe was getting ready to move on to perform in London, but Nureyev was considered a security risk by the KGB.

“I heard one of our ballet directors saying ‘Nureyev is not coming to London.’ I understood I would not be able to perform successfully back home,” said Nureyev in an interview with Volga magazine.

“So I stayed behind – having only 50 francs on my person. One company has concluded a contract with me, but the conditions were terrible. For seven nights in a row, I was performing as the prince in The Sleeping Beauty and they paid me 400 dollars – as much as the dancers of the corps de ballet made,” he said.

Nevertheless, Nureyev quickly made a successful career. He performed regularly with the Royal Ballet for years, before joining the Paris Opera Ballet as a dancer, later becoming its director.

Nureyev visited his homeland both before and after the fall of the Soviet Union. During his last visit in 1992, he even accepted an invitation to cooperate with the Tatar State Academic Opera and Ballet Theater in Kazan. Sadly, in 1993, Nureyev passed away due to cardiac complications resulting from AIDS.

Alexander Godunov

Balshoi Ballet star Alexander Godunov gestures during a press conference in New York on August 29, 1979. Source: AP

Godunov joined the Bolshoi Ballet in 1971. Just like Baryshnikov and Nureyev, he defected while on a tour with his troupe in New York City in 1979. Godunov was assisted by Joseph Brodsky, the renowned Russian poet and essayist who had been expelled from the Soviet Union in 1972.

“We took the car and went to my dacha, since it was clear Godunov needed to lay low for a while. My first advice to him was to contact someone in the State Department of the United States...” said Brodsky in an interview with Russian musicologist Solomon Volkov.

“The next day, we returned to the city to perform all the required procedures with various forms. Sasha [Godunov] was on the couch, I was sitting in the armchair, and the immigration officer was on the chair. There were also two guys from the FBI. I acted as a translator.”

Godunov's story is perhaps the most dramatic, since his wife, Lyudmila Vlasova, also a dancer at the Bolshoi, was with him during the tour – and she had no idea he was going to defect.

“We tried calling Mila Vlasova the very day Sasha decided to defect,” said Brodsky. “At first she was at the rehearsal, later she had to perform, and later still, it was simply too late to call – the KGB imposed a curfew on the artists during all tours.”

Indeed, the KGB agents traveling with the Bolshoi troupe did all in their power to stop Lyudmila from following her husband, creating an environment of isolation and psychological pressure.

Before the plane carrying the Bolshoi Ballet dancers could leave the United States, it was detained by the American authorities, who wanted to make sure Vlasova was leaving of her own free will. The plane was allowed to leave only three days later – an incident later adapted by Soviet filmmakers into the film Flight 222.

Godunov visited Russia just once in 1995, shortly before his death – but this looked more like a farewell than a return.

More U.S.-related stories in your box!

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox