How a Russian spy outfoxed the British in 19th century Afghanistan

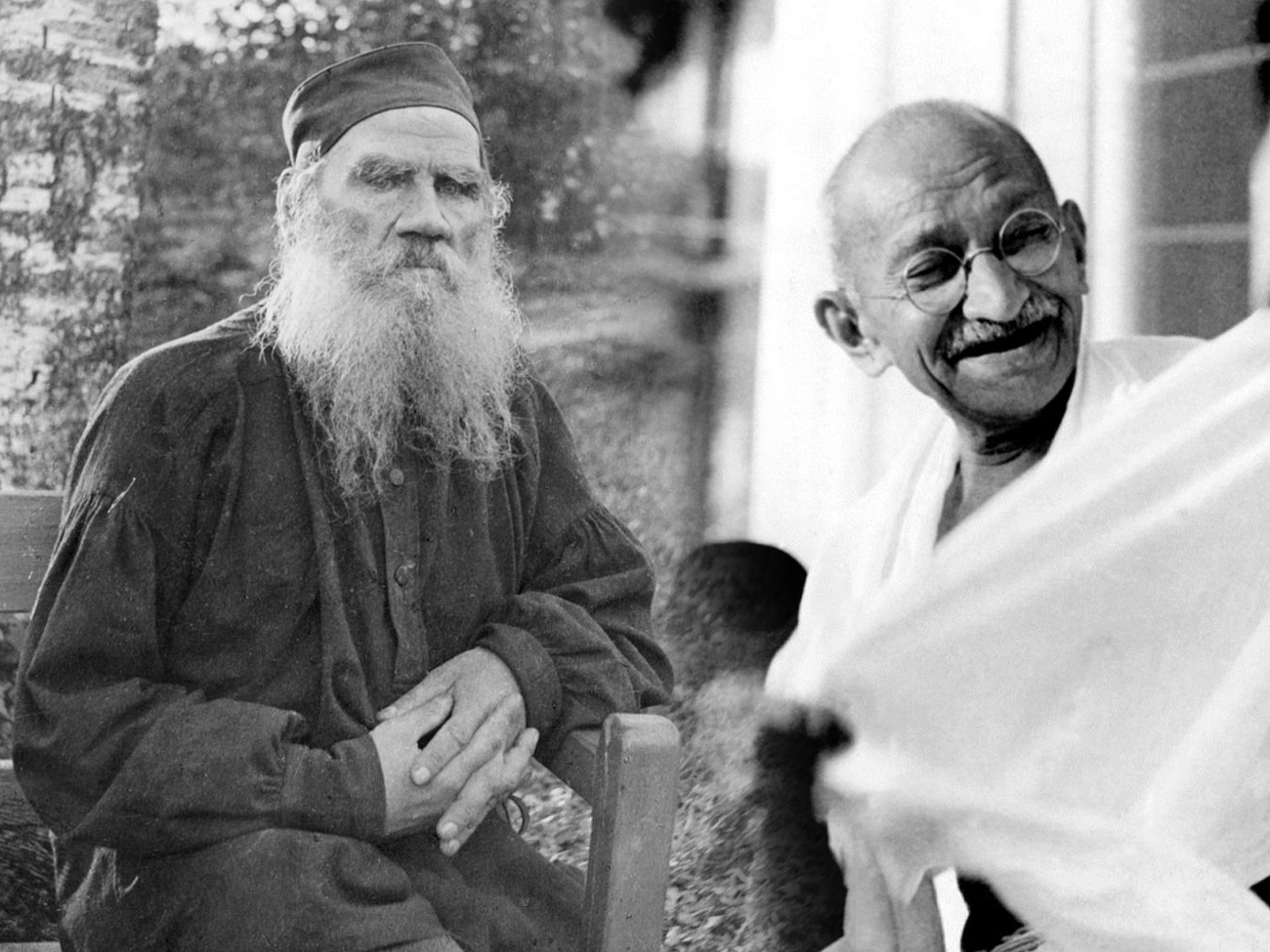

Britain and Russia jockeyed for political influence in Afghanistan in the 19th century.

Getty ImagesIn the first few decades of the 19th century, the Russian and British Empires were increasingly on a collision course. While the former was expanding southwards into Central Asia, the latter already had a strong presence in India, and it was just Afghanistan that would be a buffer state between the two empires.

Fearful of each other, Russia and Britain were each eager to at least have a friendly regime in Afghanistan. This political and diplomatic confrontation between the two empires is referred to as ‘The Tournament of Shadows’ in Russia and ‘The Great Game’ in the West.

The first major move in the diplomatic chess match was made in 1831 by Alexander Burnes, a 26-year old Scottish explorer who travelled on his own from India to Afghanistan and onwards to Bukhara.

His 1835 book ‘Travels into Bukhara’ is a fascinating account of what was then one of the most dangerous and least-explored places on earth. Burnes, who later became a British political agent in Afghanistan, also managed to initiate a dialogue with Afghan Emir Dost Mohammed Khan.

The same year that Burnes published his book, a young Russian army officer who was exiled in Orenburg (near the Kazakhstan border) was also preparing to go to Central Asia. Ivan (Jan) Viktorovich Vitkevich, then a 27-year old sergeant, was already fluent in Russian, English, German, French, and Polish, as well as Persian and Pashto.

While travelling to Bukhara via Kazakhstan, he met Hussein Ali, an envoy of Dost Mohammed Khan. This would be the beginning of an illustrious yet brief Afghanistan-related career for Vitkevich.

Weary of British designs on his country, the Afghan Emir had sent Ali to meet the Russian Tsar. Vitkevich took the Afghan envoy to Orenburg and then to the imperial capital of St. Petersburg. He served as an interpreter and helped the Russian government get valuable insights into the political situation in Afghanistan.

Rival spies in Afghanistan

Vitkevich was asked in 1837 to go on a secret diplomatic mission to Kabul. The British managed to get wind of the Russian’s mission when Vitkevich accidentally ran into a British political agent in Persian (Iran). This came with suspicions that Russia was encouraging the Persians to attack western Afghanistan.

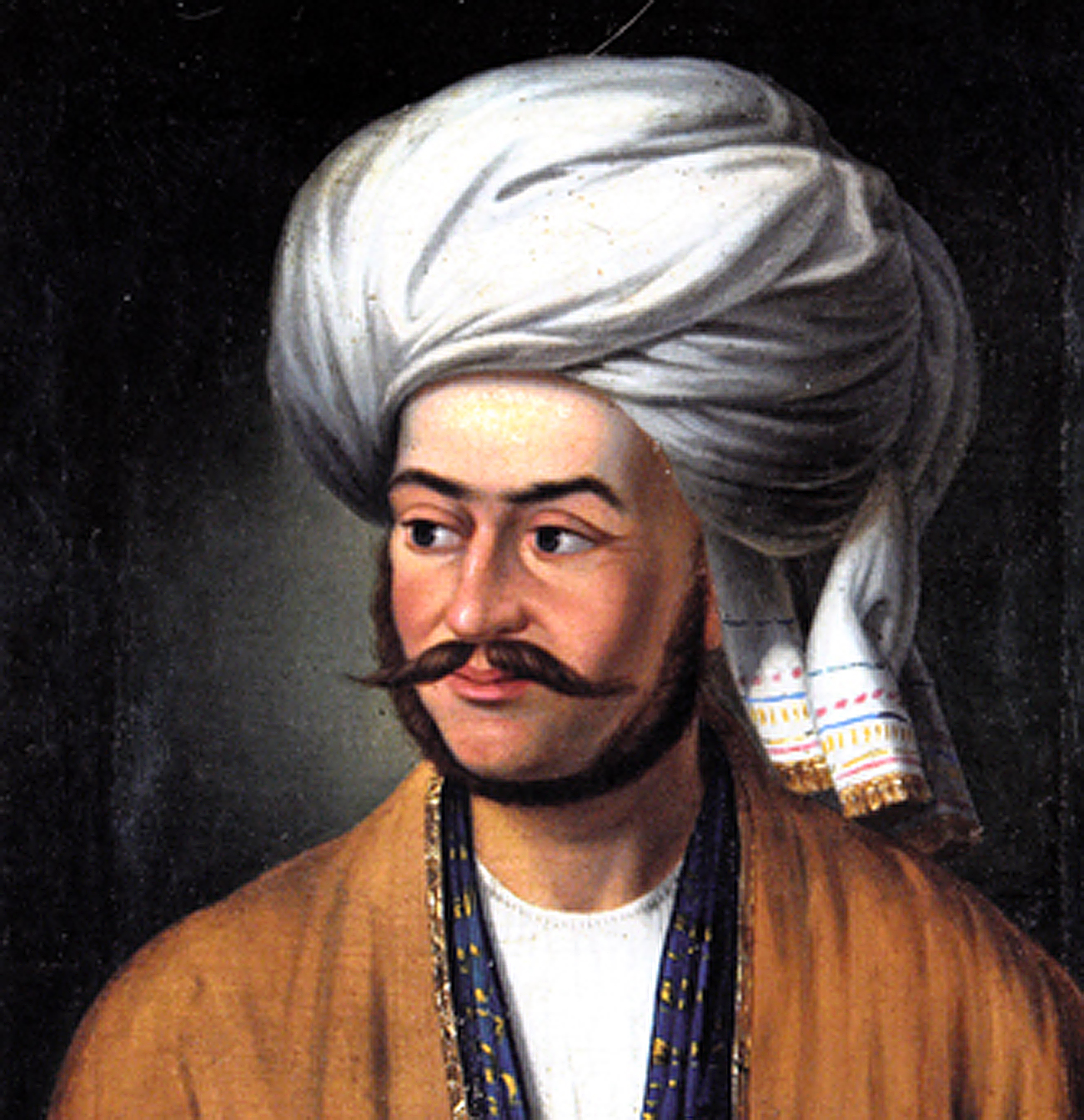

A portrait of Ivan (Jan) Vitkevich dressed in traditional Central Asian attire. Source: wikipedia.org

A portrait of Ivan (Jan) Vitkevich dressed in traditional Central Asian attire. Source: wikipedia.org

The two great travellers, Vitkevich and Burnes met in Kabul over Christmas dinner in 1837. “The Russian’s arrival terrified the British,” filmmaker and politician Rory Stewart said in a documentary titled ‘Afghanistan: The Great Game.’

“They became, in turn, very suspicious of Russia’s ambitions in this country. And this mutual paranoia led to more and more foreign intelligence operations around Afghanistan, with rival officers like Vitkevich and Burnes sending back countless reports on each others’ activities.”

Over the next few months, in addition to sending comprehensive reports on the British activities in Afghanistan, Vitkevich also managed to befriend Dost Mohammed Khan and blended in with ease in the country. Such was his reputation that the British paranoia towards Russia grew to unparalleled levels.

“Whenever the British saw a Russian painter turn up in the city, a Russian hunter turn up on the Frontier, they would immediately assume that this was a double game of espionage,” Stewart said in the documentary. “It was these fears and suspicions of empires that were to turn Afghanistan into a battleground.”

Return to Russia

It was clear by the end of Vitkevich’s time in Kabul that he managed to win over the Emir’s trust. Historical accounts state that Dost Mohammed Khan was able to extract assurances of Russian support if the British did invade Afghanistan.

Such assurances never came to fruition when the First Anglo-Afghan War took place in 1839, although the British gains in the conflict were short-lived and came at a great human cost.

British protests about Vitkevich role in Afghanistan led to St. Petersburg withdrawing the officer. He reached the Russian capital in May 1839 and was largely satisfied with the success of his mission in Afghanistan. However, a week after his return to St. Petersburg, he was found shot dead in his hotel room. A pistol and burned papers were found by his side.

His death was ruled a suicide but many historians believe he was assassinated.

“Nothing about Ivan Viktorovich Vitkevich’s notably Dostoyevskian death made much sense, and almost from the moment the body was discovered, the mysterious end of Russia’s first agent of The Great Game became the subject of speculation,” historian William Dalrymple wrote in his book ‘The Return of a King: The Battle for Afghanistan.’

The British suspected the Russian government of killing Vitkevich, despite the fact that he outmaneuvered Burnes in Afghanistan. Russian historians have placed the blame on the British.

“For many Russian observers, however, the mysterious death couple with the disappearance of Vitkevich’s Afghan papers bore all the hallmarks of British foul play,” Dalrymple wrote. “After all, Vitkevich’s papers contained details of the British intelligence and news-writing networks in Central Asia that he had successfully penetrated.”

Burnes was murdered by a mob in Kabul in 1841.

Vitkevich’s life was the inspiration for several Russian books such as Yulian Semyonov’s ‘The Diplomatic Agent’ and Mikhail Gus’s ‘Duel at Kabul.’ He is also the prototype of the leading character in the Soviet film ‘Service to the Homeland,’ which was produced in 1981. However, unlike Alexander Burnes, whose legacy is celebrated in Britain, Ivan Vitkevich is largely forgotten in 21st century Russia.

Read more: Badaber uprising: When Russian POWs took on the Pakistani army and the CIA

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox