How the Russian Avant-Garde came to serve the Revolution

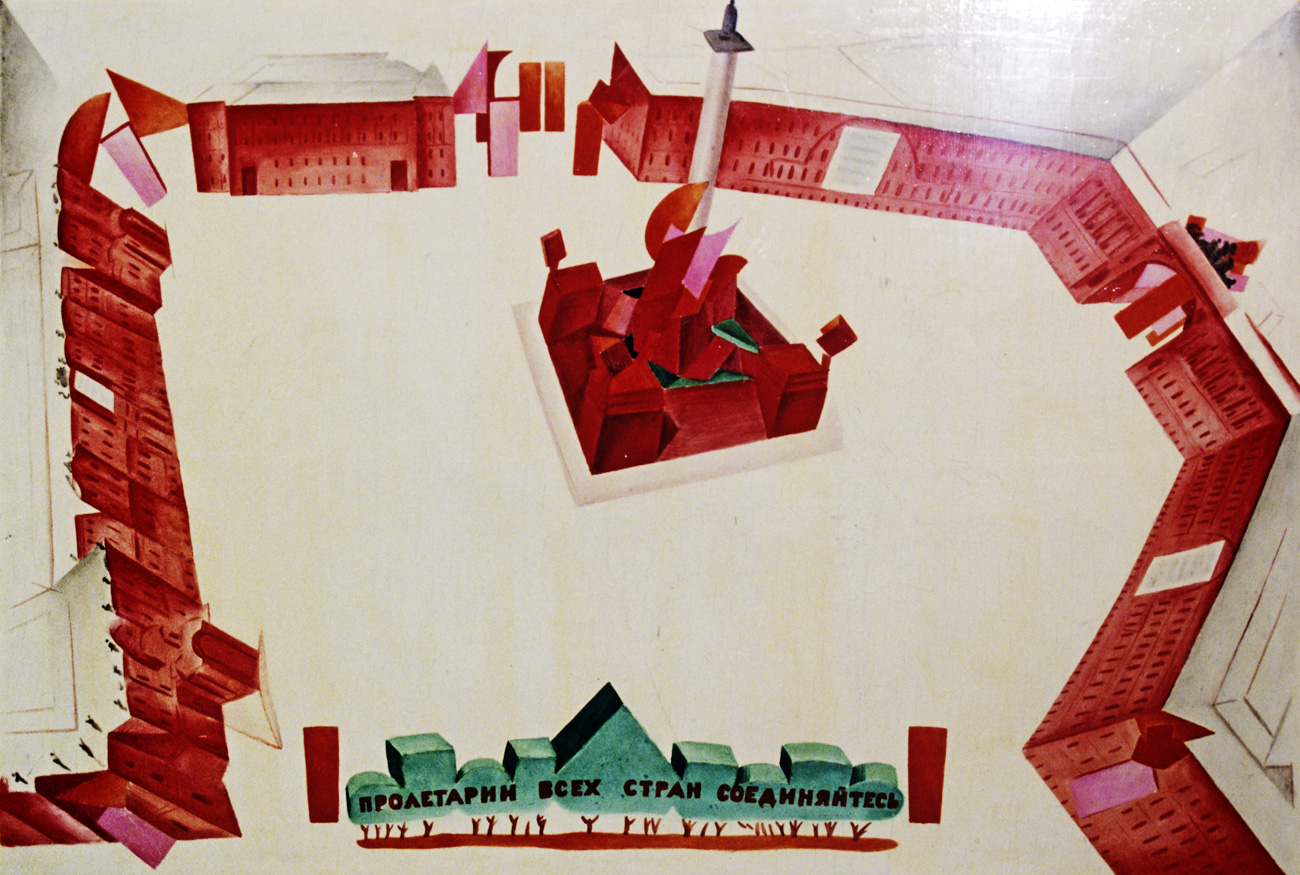

"Proletarians of All Countries Get United!", by El Lisitsky (Lazar Lisitsky). Reproduction. / RIA Novosti

"Proletarians of All Countries Get United!", by El Lisitsky (Lazar Lisitsky). Reproduction. / RIA Novosti

There is this romantic theory that the revolution in Russian arts contributed to the political revolution in the country. The Russian avant-garde, the reasoning goes, in its search for new formats and dismissal of the old dogmas, resonated so closely with political events that it came to serve as the revolutionary movement's primary mouthpiece for a number of years.

The origins of the Russian avant-garde are usually dated to 1908, the year in which Moscow and St. Petersburg hosted exhibitions that featured young rebel artists like the Burliuk brothers, Mikhail Larionov, Natalia Goncharova, and Aristarkh Lentulov. In the following nine years until the revolutionary year of 1917, the avant-garde movement developed at a breakneck pace.

Many avant-garde artists embraced the revolution. It suddenly turned out that their artistic ideas were resonant with political slogans, such as Kazimir Malevich's proposal to burn all paintings and exhibit their ashes in museums, because - he asserted - there would be no art after Suprematism. Tragically, this idea was implemented in the first months of the 1917 revolution.

The new state needed fresh, vivid images that appealed to its vision of the future. Avant-garde fitted the bill nicely. In exchange, the government became the primary customer for artistic works and also the main censorship authority (although it took artists some time to fully understand this latter function).

Monumental propaganda

In the first months following the revolution, avant-garde artists found themselves involved in arranging new celebrations staged by the Soviet State. Painted hoardings on the facades of buildings in the main squares of Moscow and Petrograd (formerly St. Petersburg) were true masterpieces of monumental art. Unfortunately, none has survived. All these pictures were devoted to the new symbols and the new people - workers and peasants.

Sketch of decoration for Palace Square by painter Nathan Altman (1889-1970). Reproduction. The State Russian Museum in Leningrad (St. Petersburg currently). / Rudolf Kucherov/RIA Novosti

Sketch of decoration for Palace Square by painter Nathan Altman (1889-1970). Reproduction. The State Russian Museum in Leningrad (St. Petersburg currently). / Rudolf Kucherov/RIA Novosti

In 1918, futurist painter Olga Rozanova was involved in decorating Moscow for May Day, a new 'workers' holiday on May 1st. Rozanova employed her abstract technique and made full use of fireworks and illumination. On the first anniversary of the revolution, artist Nathan Altman wrapped the wings the Hermitage museum in Petrograd in scarlet fabric (nearly 80 years later, the artist Christo would wrap the Reichstag building in a similar way, producing an international sensation). The Alexander Column in Palace Square was decorated with Suprematic compositions. Never before or after did Moscow and Petrograd look as avant-garde as in the first years following the Bolshevik revolt.

Word and image

Propaganda then spread to printed matter: Posters, magazines, and books. Cubo-Futurism, Constructivism, and Suprematism with their simple shapes and unimposing structure fitted the new requirements ideally.

Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge El Lissitzky. / Van Abbemuseum

Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge El Lissitzky. / Van Abbemuseum

El Lissitzky's 1920 poster “Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge” is a good example of how a Suprematist composition would be filled with political content.

Another striking example of the time is the 1924 advertisement by Alexander Rodchenko urging people to buy books by Lengiz Publishing House. Close-up views, angle shots, diagonal lines running across the pictures, these are all the signature methods that Rodchenko used to turn his Constructivist photographs into both utilitarian advertising and artistic masterpieces.

The "Alexander Rodchenko. Photography- Art " Album. / Press Photo

The "Alexander Rodchenko. Photography- Art " Album. / Press Photo

Revolutionary design

The Utopian desire to transform everything within reach gave birth to the idea that people could be influenced not just through monumental arts but also by ways of creating a new visual world around them so that in everyday life, modern objects would be ubiquitous in their surroundings. This is how Soviet industrial design emerged.

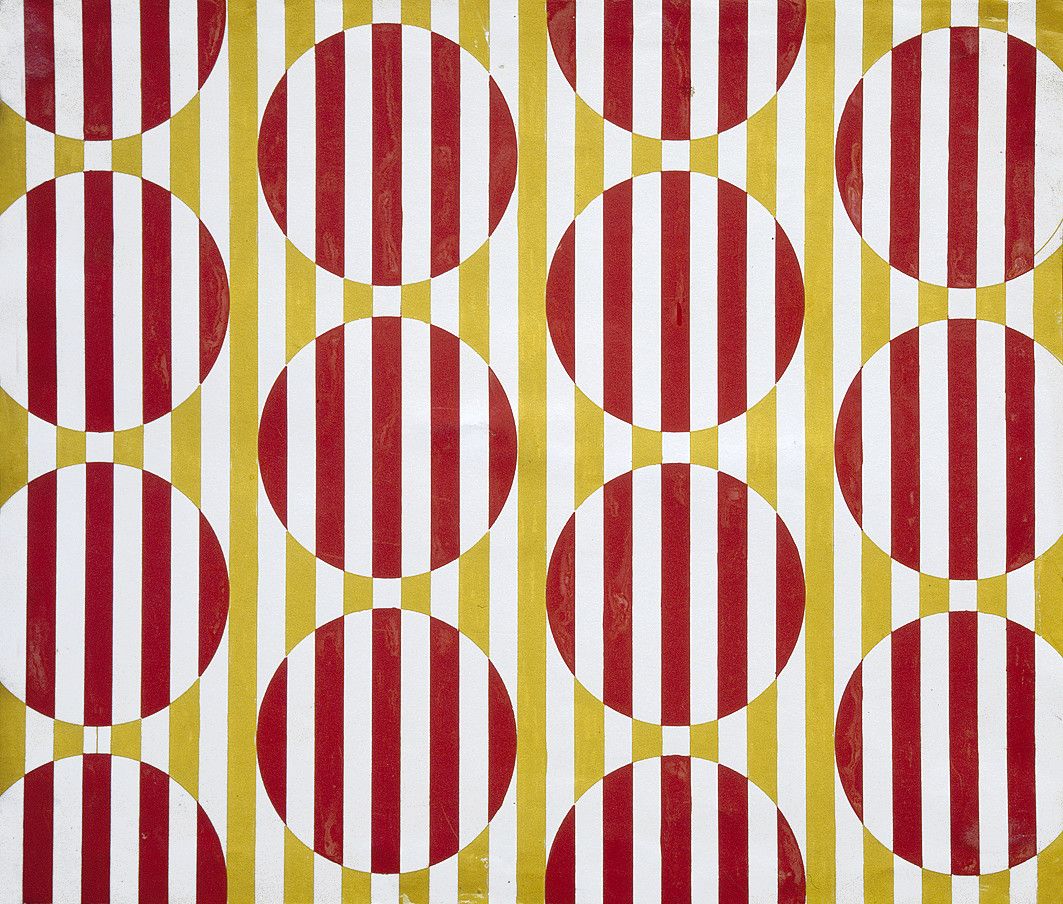

Varvara Stepanova. Design for textile, 1924. / Private collection

Varvara Stepanova. Design for textile, 1924. / Private collection

Varvara Stepanova and Lyubov Popova, two of the most prominent women of the Avant-Garde, developed new fabric designs for a textile factory that were meant to replace pre-revolution motifs.

Performance at a book evening, USSR, 1924. The costumes were designed by the artist Varvara Stepanova. Found in the collection of the Russian State Archive of Literature and Art, Moscow. / Getty Images

Performance at a book evening, USSR, 1924. The costumes were designed by the artist Varvara Stepanova. Found in the collection of the Russian State Archive of Literature and Art, Moscow. / Getty Images

The cheap chintz mass-produced in Soviet Russia for clothing now got abstract geometrical patterns in contrasting colors. Stepanova also designed “industrial clothes” for different professions. Her principles included geometric shapes, a unisex approach, and no decorative frills.

Sketch of a fabric with the color triangles ornament, 1923-1924. / Tretyakov Gallery

Sketch of a fabric with the color triangles ornament, 1923-1924. / Tretyakov Gallery

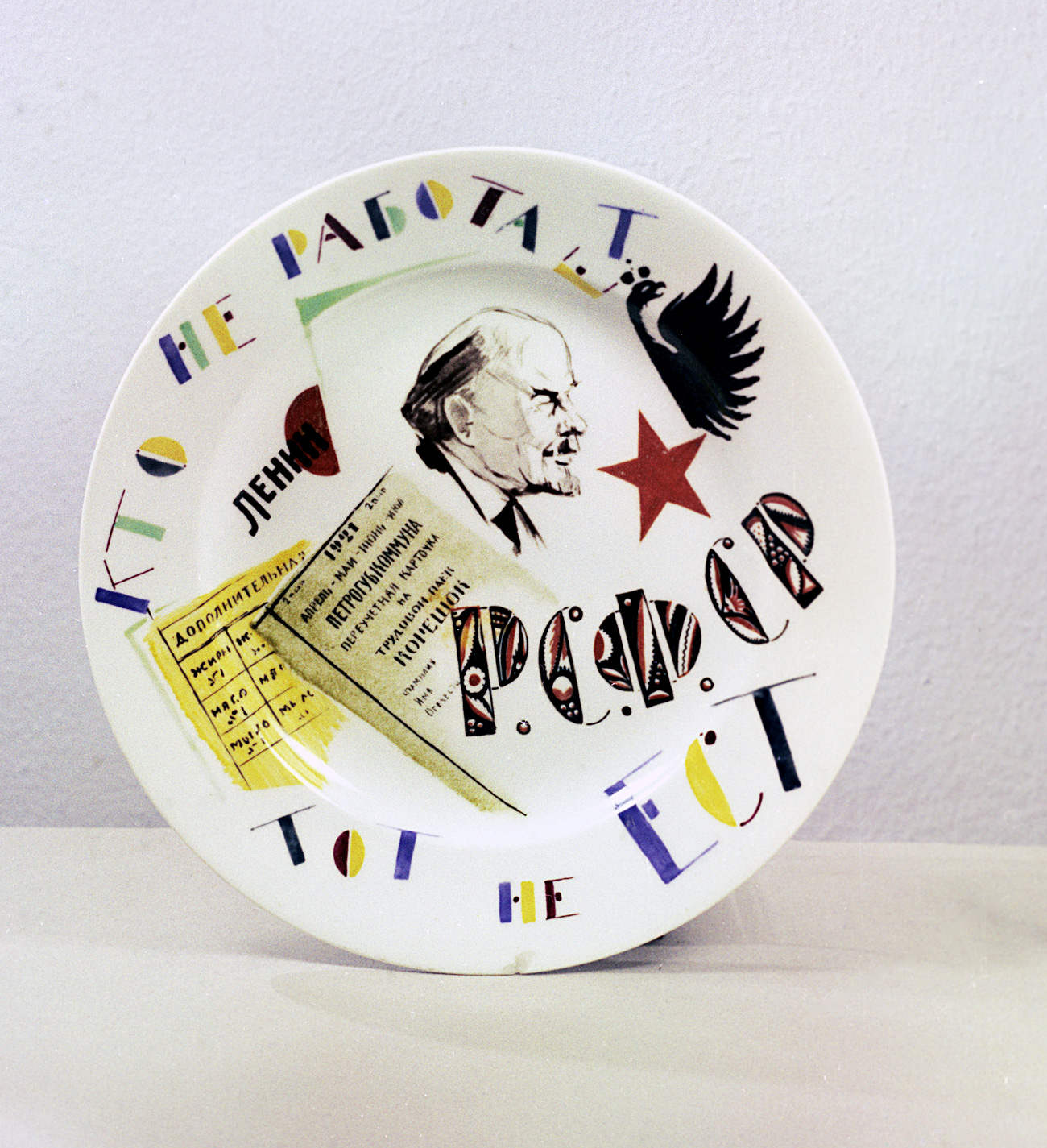

'Agitation porcelain'

Another avant-garde manifestation of the times was so-called agitation porcelain: Pieces of ceramic pottery with pro-Bolshevik designs, which now fetch high prices on the international art market. These were produced at the former Imperial Porcelain Factory under a nationwide monumental propaganda program, and mostly exported. Malevich with his understudies Nikolai Suetin and Ilya Chashnik experimented with Suprematically shaped teapots and teacups. The cups were not very convenient for everyday use, but they did look impressive.

Teapot by Kazimir Malevich is on display at the avant-garde porcelain exhibition їAround the Squareо at the State Hermitage Museum. / Yuri Belinsky/TASS

Teapot by Kazimir Malevich is on display at the avant-garde porcelain exhibition їAround the Squareо at the State Hermitage Museum. / Yuri Belinsky/TASS

A huge part of agitation porcelain came in the form of platters bearing revolutionary slogans by Alexandra Shchekotikhina-Pototskaya and Sergey Chekhonin, who both borrowed ideas from Russian and French Modernists. Many of their designs were based on erstwhile motifs but told new stories. Sculpture, for its part, offered truly revolutionary plots such as Natalya Danko's The Reds and the Whites porcelain chess set, in which the white pieces are represented by Death and slaves, covered in the chains of Capitalism, and the red pieces are peasants with sickles, Red Army servicemen, and a worker with a hammer.

A plate with "Who doesn't work, doesn't eat" and portrait of Vladimir Lenin painted on it. Author - M. M. Adamovich. 1920. State china plant. Saint-Petersburg. State ceramics museum and "Ensemble Kuskovo. XVIII." / Я.Юровский/RIA Novosti

A plate with "Who doesn't work, doesn't eat" and portrait of Vladimir Lenin painted on it. Author - M. M. Adamovich. 1920. State china plant. Saint-Petersburg. State ceramics museum and "Ensemble Kuskovo. XVIII." / Я.Юровский/RIA Novosti

Architecture

Architecturally, revolutionary ideas were manifested through Constructivism. In the early years after the 1917 revolution, while civil war was ravaging the country, there was not enough money to build anything new. Many of that period's projects remained on paper or in the form of scale models.

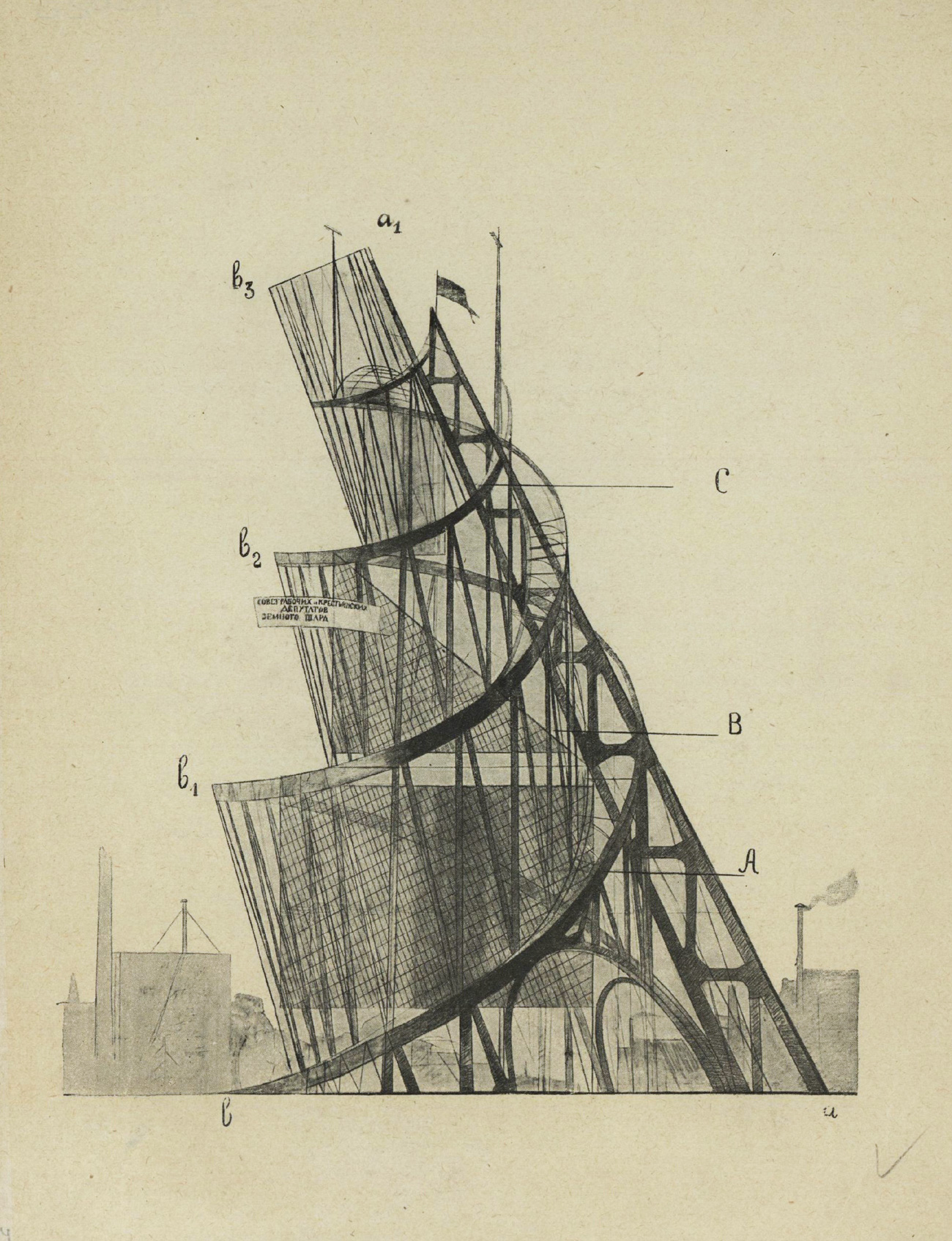

Tatlin’s Tower, or the project for the Monument to the Third International. / Archive photo

Tatlin’s Tower, or the project for the Monument to the Third International. / Archive photo

The most renowned of these is the project to build a monument to the Third International (an association of international Communist parties) created by Vladimir Tatlin in 1919. The tilting steel frame was to contain three objects made of glass: A cube, a cylinder, and a cone. These were designed to rotate at different rates, completing one circle within one year, one month, and one day, thus counting the time passed since the beginning of the new era. Had the project been realized, it would have been taller than the Eiffel Tower.

Avant-Garde and Realism

Painters also created new images. Artistic associations continued to boom in the 1920s, with new groups forming around such prominent avant-garde figures as Malevich, Pavel Filonov and Mikhail Matyushin. Most of the existing avant-garde associations found new applications to their activity.

Petr Williams. Motor rally, 1930. / Tretyakov Gallery

Petr Williams. Motor rally, 1930. / Tretyakov Gallery

One of the key ones was the Society of Easel Painters, which drew on the European and Russian avant-garde experience in poeticizing the real world. Its symbols were Piotr Williams's expressive Motor Rally and Aleksandr Deyneka's The Defense of Petrograd. At the other extreme, the Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia, whose members strove to record the events of the country's new history without any attempt at aestheticism, represented the painting community.

The defense of Petrograd, 1956. / Tretyakov Gallery

The defense of Petrograd, 1956. / Tretyakov Gallery

Portraits of party leaders and paintings of incessant party congresses would become the mainstream of Socialist Realism in the 1930s. It appears that Realism's victory over Avant-Garde had been predetermined: Vladimir Lenin, the leader of the Russian Revolution, had said that arts had to be kept simple and that content was more important than artistic format.

The diversity of Soviet arts was cut short in 1932, when the government banned all artistic associations. Four years later, the country started fighting any manifestation of “formalism”. This drove the remainders of the avant-garde movement underground for good.

Read more: 6 unmissable films about the 1917 Russian Revolution

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox