In this grim place you'll feel the pain and suffering of millions of Soviet citizens.

Children who were once labeled "enemies of the people" are now advanced in their years, but they can still recall the most terrible moments of their lives, when people in uniforms came for their parents late at night - the last time they ever saw them. Today, a young woman watches these video interviews in a room at the Gulag Museum. She starts to cry. A group of high school students hang on the guide's every word, dismay written on their faces. It seems they find it difficult to imagine that in the 1930s kids their own age found themselves behind barbed wire. Meanwhile, a group of foreigners sit in the museum cafe, trying to digest what they have just seen and unable to say a word.

In a prisoner's shoes

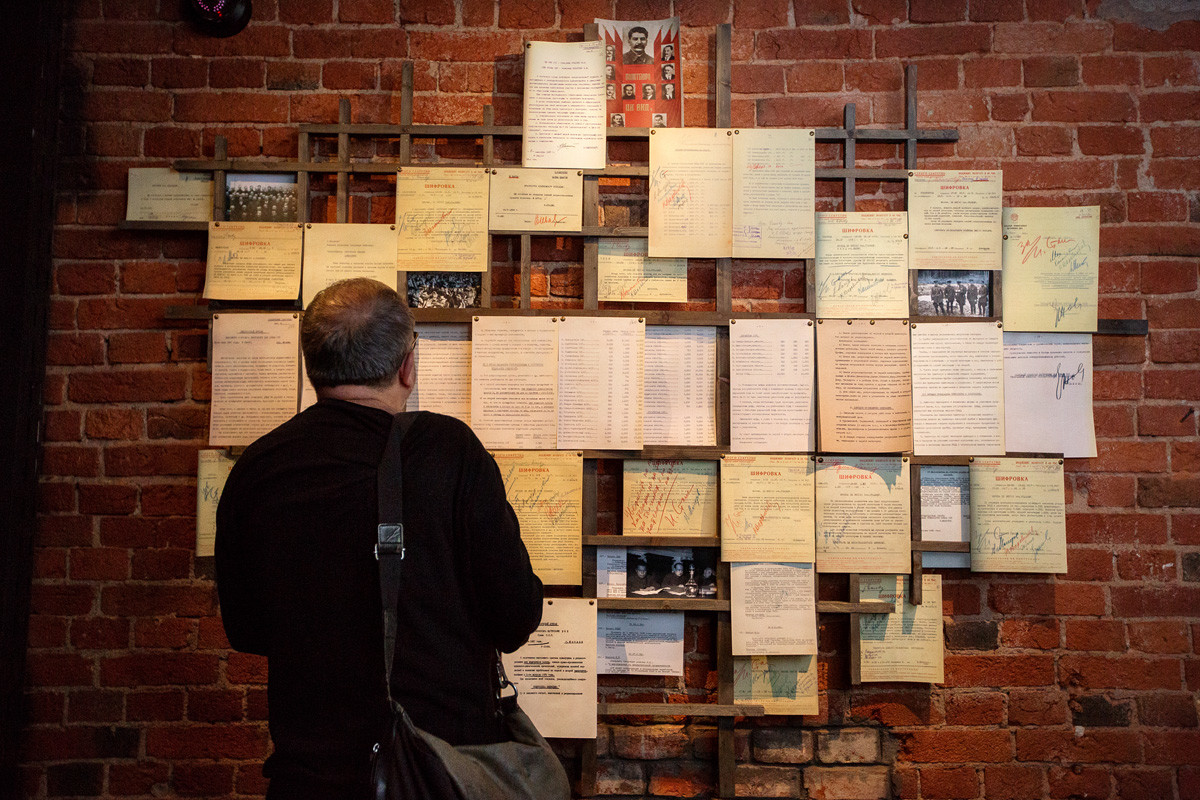

The Gulag History Museum used to be based in a tiny building, but it recently moved to new premises and, with its huge archive, it now has a home of its own. The designers tried to make it look like a prison camp: intimidating steel gates, brickwork, dim light and lots of sullen and drab black color. From the very first minute, a visitor is immersed in the atmosphere of the darkest side of Soviet power - the terrible years of the Great Terror and repressions.

In the first room, you're greeted by numerous doors – a door from a camp barracks, a door from a cell in a remand prison in Magadan, a door from one of the Seven Sisters buildings in Moscow, from where people were taken away forever – it is a metaphor of moving to another, terrible world.

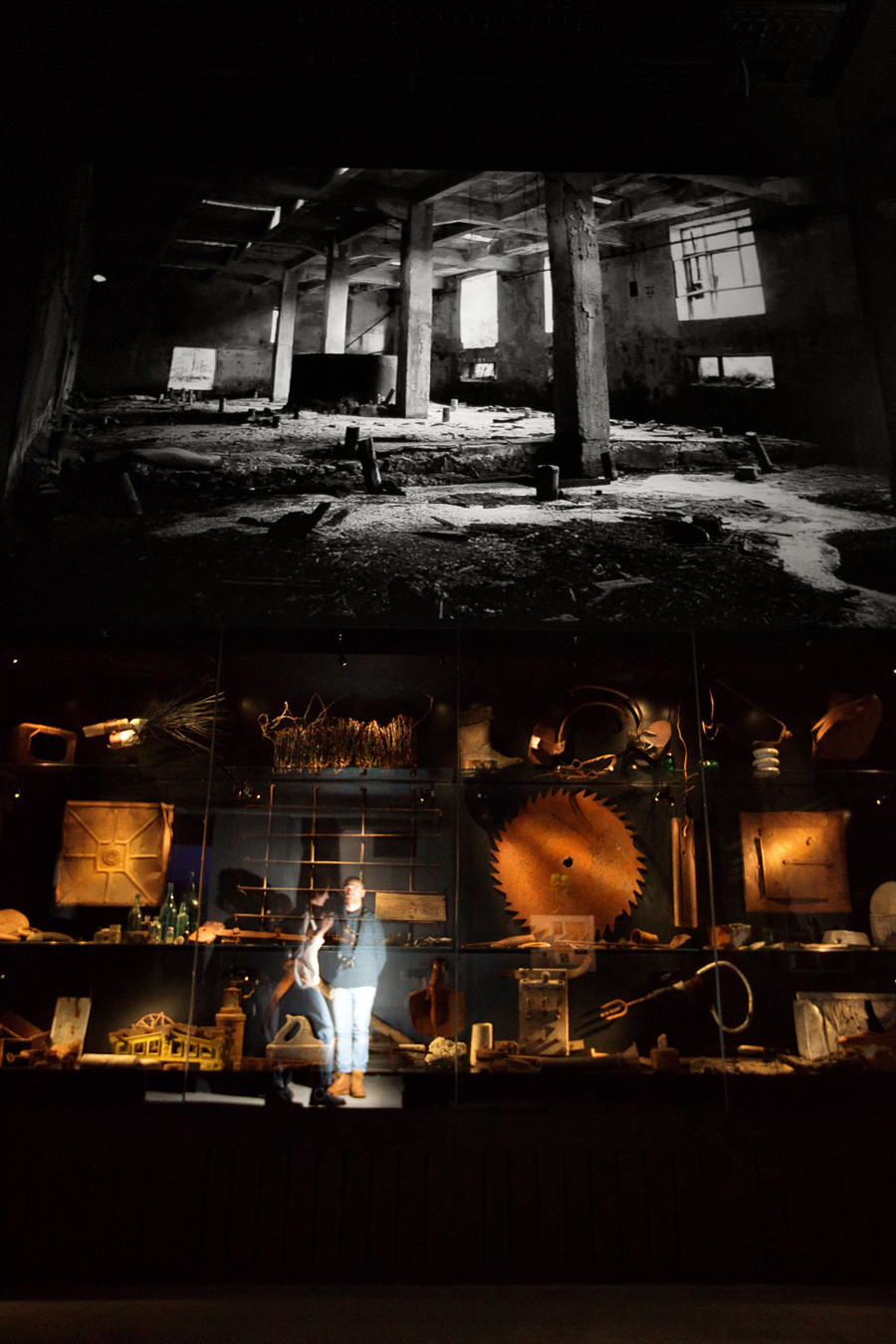

In the execution chamber, the floor is strewn with empty casings, while portraits of the murdered are projected onto a brick wall, one replacing another to the sound of cocking the gun. Archival footage shows prisoners working at a logging camp. There are personal items, including those found in mass graves. Once you're surrounded by all this, it is difficult to recover.

A system of reprisals from 1917 to Stalin's death

The purpose of the museum is to trace not only the history of the camps themselves, but of the entire system of political repressions. In order to show how executions without trial and investigation became part of the legal practice of the USSR, the museum displays documents, NKVD resolutions and quotes from leaders of the Revolution.

The Soviet authorities believed that in order to build a new world, it was necessary to exterminate people who, in one way or another, allegedly sabotaged it. The list of these categories of people was forever expanding. “Repression for the attainment of economic ends is a necessary weapon of the socialist dictatorship,” said one of the main ideologists of the revolution, Leon Trotsky.

The first political prisoners in the USSR were put into existing prisons and monasteries, from where monks were being expelled. A separate section of the exhibition is devoted to the Solovki Special-Purpose Camp, the first of its kind. Later, in the 1930s, during the years of the Great Terror, camps were built across the country and convict labor became one of the pillars of the Soviet economy.

For the first time, Gulag is presented through multimedia

The museum also offers audio versions of memoirs of people who went through the camps: the author of The Kolyma Tales, Varlam Shalamov; Alexander Solzhenitsyn (who has a separate room dedicated to his life); Leo Tolstoy’s daughter Alexandra; and many others.

An interactive map of the Gulag shows the chronology, location, number of prisoners and types of camps (corrective labor, special, screening and filtration) throughout the country. It is available online, so you can see it without visiting the museum - gulagmap.ru.

With the help of a VR helmet, you can take a virtual tour with museum director Roman Romanov around what remains of the Butugychag camp in the Russian Far East, where inmates worked in uranium mines without wearing any radiation protection. The museum plans to develop more virtual tours like this.

All information in the museum is translated into English; same as all the audio materials, and the videos have English subtitles. The museum has a documents center, where one can get information about victims of repressions.

In the last room, a voice on the speaker system reads out the names of people who were wrongfully convicted and killed. A young couple, holding hands and motionless, listen to the seemingly endless list. As part of the finale, there are horrifying figures displayed on the black wall: during the Great Terror, more than 20 million people were sent to prison camps; two million died there, and 700,000 were executed.

Watch Russia Beyond documentary: The memory of the Solovetsky islands

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.