And he wasn’t alone in his search for truth. We’ve put together a list of the writer’s “partners in crime”, who lived in different times, but also chose to burn their works “after reading”.

Throughout his entire life, the author of ‘The Diary of a Madman’ suffered from mood swings. When Gogol created his signature, grotesque works like ‘The Nose’ or ‘The Overcoat’, he would dance in the middle of the street in ecstasy. But joy was quickly replaced with frustration and anxiety.

Portrait of Nikolai Gogol, by Otto Friedrich Theodor von Möller.

Gogol’s major magnum opus, ‘Dead Souls’ was initially conceived as a trilogy. The literary challenge was to draw a multifaceted picture of the society that “all Russia would respond to”. The problem was, the perfectionist in Gogol failed to live up to the high standard he had set for himself.

The first part of the ‘Dead Souls’ saw the light of day in 1842 and received mixed reviews. When publicist Konstantin Aksakov likened Gogol to Homer and Shakespeare, acclaimed literary critic Vissarion Belinsky fired back, saying that “Gogol resembles Homer… as much as the gray sky and pine groves of St. Petersburg resemble the bright sky and laurel groves of Hellas”.

After literary critics accused Gogol of willfully distorting reality, his satirical novel ‘Dead Souls’ also began to seem somewhat insignificant to him. A severe self-critic, Gogol said that the first part of ‘Dead Souls’ was like “a porch hastily attached by a provincial architect to a palace, which is conceived to be built on a very large scale”. But setting his goals that high, Gogol drove himself into a trap.

The second part of ‘Dead Souls’ was eagerly awaited. Moreover, Gogol mentioned it so often that a rumor quickly spread among his friends that the book had allegedly been finished.

READ MORE: Great Russian writers who didn’t do so well at school

In reality, Gogol was struggling to write the second part. The undertaking provoked a severe creative crisis. “I tortured and forced myself to write, I went through suffering and was overwhelmed by a sense of impotence… and yet I couldn’t do anything about it - everything came out wrong,” Gogol acknowledged.

In 1845, in a state of emotional turmoil, he burned the second part of ‘Dead Souls’ (that took him five years to write) for the first time. But the writer didn’t stop there and later “did it again”! In 1852, Gogol burned another almost finished second part of the ‘Dead Souls’.

Ten days later, slipping back into depression, the writer passed away, apparently starving himself to death under the guise of fasting… Apparently, Vladimir Nabokov was right when he described Gogol as “the strangest poet and prose writer Russia ever produced”.

The bigger the talent, the deeper the doubt, or so it seems. Being the leading light of Russian poetry, Alexander Puskkin was not a man devoid of self-doubt. Pushkin’s drafts were often filled with torn out pages. In the old days, when paper shredders didn’t exist, Pushkin chose to fight doubt with fire.

Portrait of Alexander Pushkin, by Orest Kiprensky.

The author of ‘Queen of Spades’ burned the second part of his famous unfinished novel ‘Dubrovsky’, the drafts of his historical novel ‘The Captain's Daughter’ and his poem ‘The Robbers’.

“I burned ‘The Robbers’ - and they deserved it!” Pushkin wrote in a letter to poet and critic Alexander Bestuzhev in 1823.

READ MORE: Top 5 books Pushkin loved to reread

The poet left the tenth chapter of ‘Eugene Onegin’, his famous novel in verse, in the form of encrypted quatrains. Pushkin planned to return to the manuscript sometime later, but it never happened. It’s believed that Puskin destroyed the tenth chapter for fear of political persecution, as it probably dealt with the Russian Decembrists revolt.

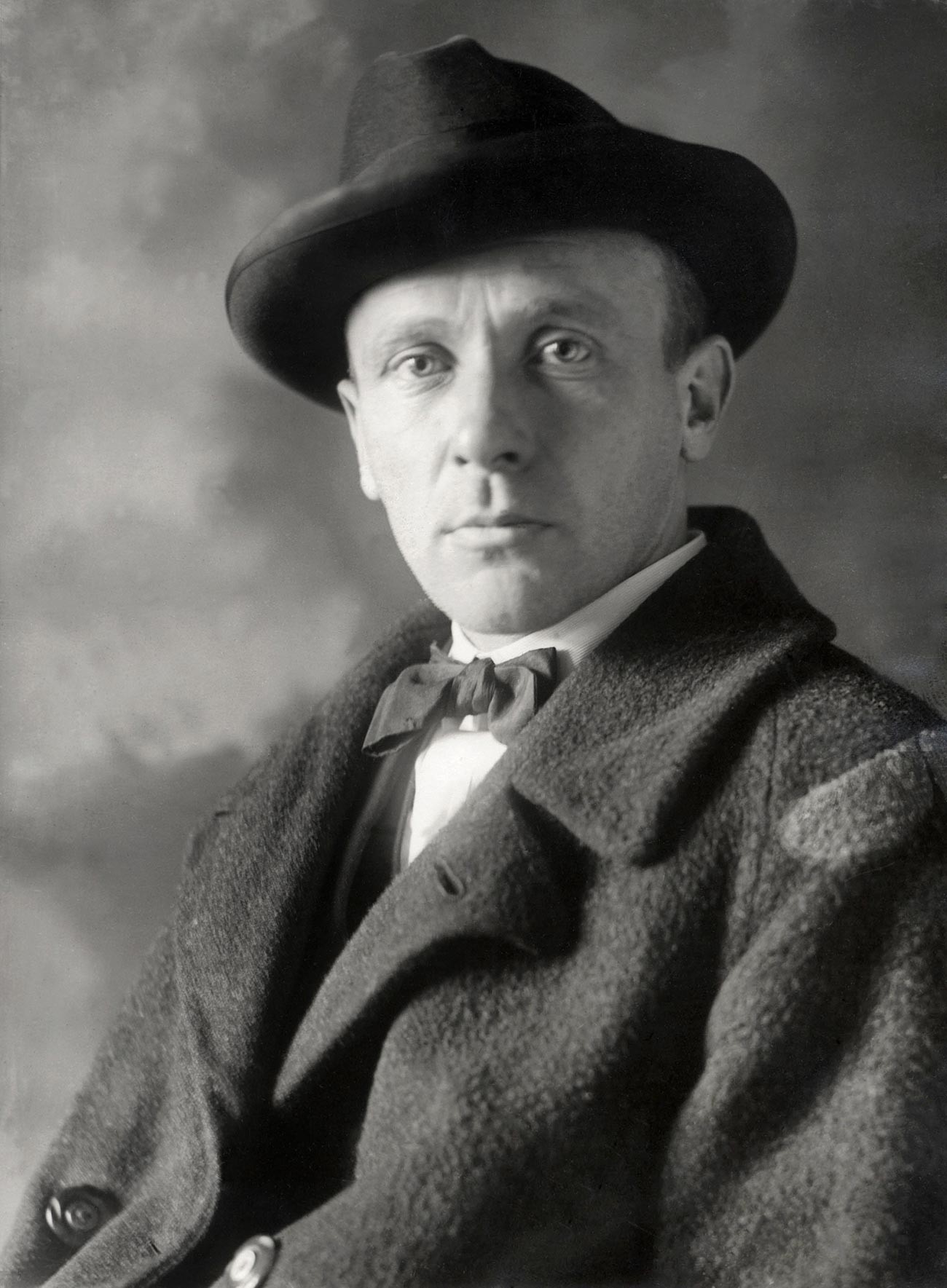

“The stove has already become my favorite editorial board,” Bulgakov admitted in a letter to one of his old friends, with a twist of sad irony. “I like her because she, without rejecting anything, with equal willingness absorbs receipts from the dry cleaner, unfinished letters and even, oh shame, poetry!"

Mikhail Bulgakov in 1928.

SputnikThe author of ‘The Master and Margarita’ believed that “Manuscripts don’t burn!” He coined that pithy phrase to prove that the written record of the writer’s work is first and foremost inscribed in memory rather than on paper.

Bulgakov was ruthless with himself and burned the first version of ‘The Master and Margarita’. The novel had a different title back then. Bulgakov wanted to call it either ‘The Black Magician’ or ‘A Juggler with a Hoof’, with the Woland character as the focal protagonist. Researchers believe that the writer did not initially plan to burn the novel, but did it in the heat of the moment, when Soviet censorship banned his play ‘The Cabal of Hypocrites’.

“A demon has possessed me…. <...>” Bulgakov later recalled. “I began to smudge page after page of my novel... What for? I don’t know. Let it fall into oblivion!”

A year later, he resumed work on the novel: a draft version appeared under the name of ‘The Great Chancellor’.

Bulgakov also turned to ashes the first draft of the second and third part of his masterpiece ‘The White Guard’. The writer’s diaries were all mercilessly “burned after reading”, too.

The author of ‘Doctor Zhivago’ never wanted to leave a legacy at life’s end. Like Frank Sinatra, he chose to have it “his way” instead.

Boris Pasternak

SputnikWith fanatical scrupulousness, Pasternak burned all first drafts of his works. If, according to the poet, the text was deemed to be weak, it was destroyed with special zeal and fervor. Destruction awaited not only unfinished manuscripts, but completed works, as well.

Pasternak’s play ‘In This World’, which was met with severe criticism, was immediately sent to the oven. His novel ‘Three Names’, which took Pasternak a year to write, didn’t escape a similar fate. He parted with the manuscript without regret, as it reminded him of his first wife Eugenia.

In Soviet times, many poets and writers destroyed their works for political reasons. They feared reprisals from the state.

Anna Akhmatova

Moisei Nappelbaum/SputnikFor example, before burning her straightforward verses, Anna Akhmatova (author of the poem ‘Requiem’, which describes the terrifying years of Stalin purges) learned them by heart and read her latest compositions out loud to friends, for them to remember and pass on by word of mouth. Akhmatova’s poems were therefore inscribed in the memory of her closest and most trusted friends, Osip Mandelshtam among them. Their friendship lasted nearly 30 years. Akhmatova said that Mandelshtam was one of the “most pleasant talkers” she had ever met. Osip, in turn, admired Anna’s beauty, character and truth, saying that her poetic lines “can only be removed surgically”.

One of the greatest poets of the 20th century was realistic enough to admit that his works could cost him his head. The poet was forced to burn, hide or give copies of the manuscripts of his poems to family members. To keep his poetry alive, Mandelshtam had to share it with his best friends.

Osip Mandelshtam

SputnikIn 1933, Mandelshtam produced a knife-edged epigram on Stalin: “We live unable to sense the country under our feet.” Shortly after, the poet was arrested and sent into exile.

READ MORE: Top 3 Jewish writers who clashed with the Soviet system

“We had to restore the verses, because after all the shocks (police raid, arrest, exile, illness), many things just blanked out. The rescued manuscripts... ended up in saucepans or inside the shoes,” the poet’s wife Nadezhda Mandelstam recalled in her heart-wrenching memoir ‘Hope Against Hope’.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox