Boris Pasternak is one of the most prominent Russian writers of all time. Despite this fact and the fact that he is internationally renowned and now absolutely adored in Russia, in Soviet times, he was a persona non grata.

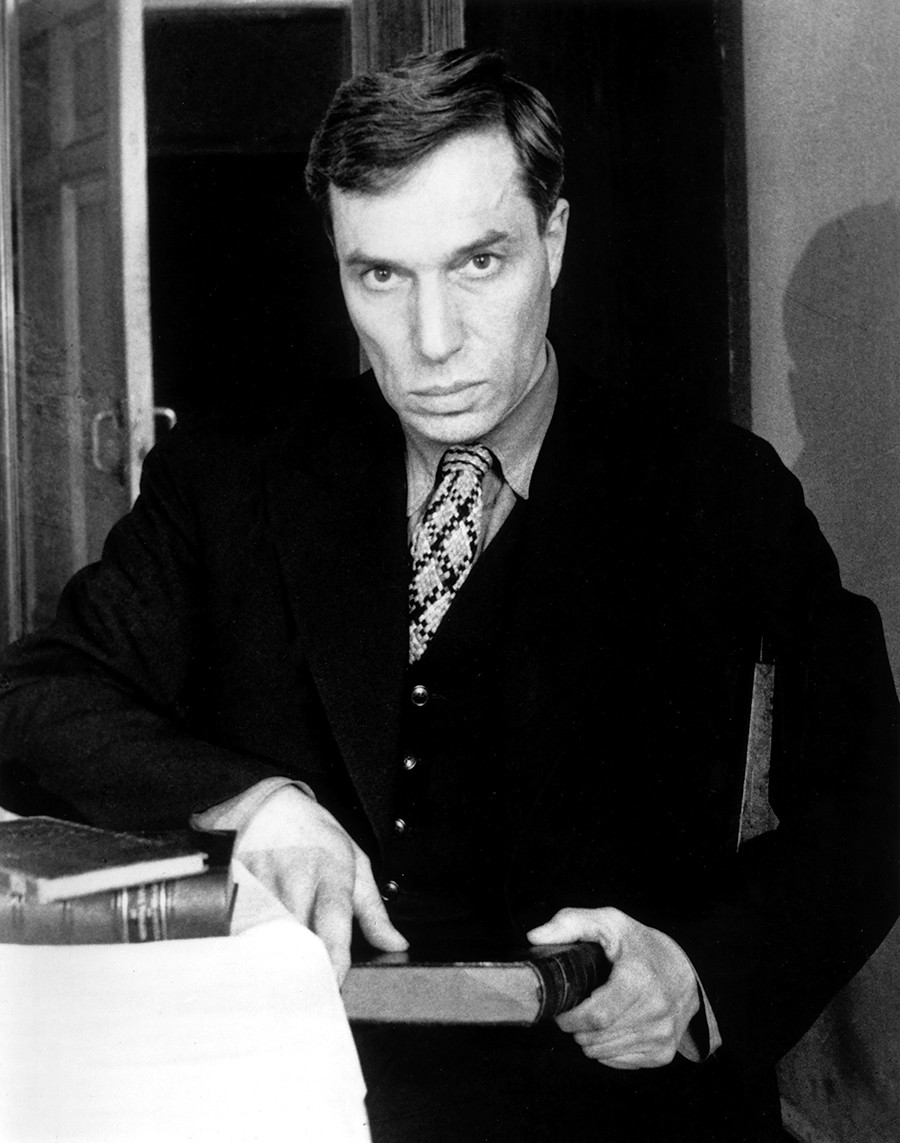

Boris Pasternak

ullstein bild/Getty ImagesBoris Pasternak was most commonly known as a poet, and his symbolist verses are considered to be part of the Silver Age of Russian literature, time of the most fruitful and talented poets in Russia.

Pasternak didn’t quit the country after the Bolshevik Revolution, as many writers and most of his family members did. He kept on writing poems - and became recognized by the Soviet authorities. In the 1920-30s, he was considered as one of the best Soviet poets and he was a respectful member of the Soviet Union of Writers. Even Joseph Stalin appreciated his figure and talent - and most likely because of Pasternak’s personal request to Stalin, after which several people were set free from jail.

However, with the strength of Stalin’s reign, from the late 1930s, Soviet propaganda required patriotic spirit-lifting poems, not philosophical and “detached from real life” lyrics, as Pasternak had. So, his poems ceased to be published from that moment on and he began turning to translations and prose.

After working for about 10 years, in 1955, Pasternak completed one of the best novels ever written in the Russian language - Doctor Zhivago. Formally, it’s a book about the Civil War that happened in Russia after the Revolution, but, deep down, it’s a novel about human beings, about love and death, the meaning of life and the universe itself. And absolutely inappropriate in Soviet times, as the novel does not put the Bolsheviks in a good light and, instead, shows how barbaric they acted and how they ruined many lives.

Unsurprisingly, Doctor Zhivago was banned from publication and raised a wave of negativity from the media and the authorities, including Nikita Khrushchev. And what happened next literally “killed” Pasternak as a Soviet writer.

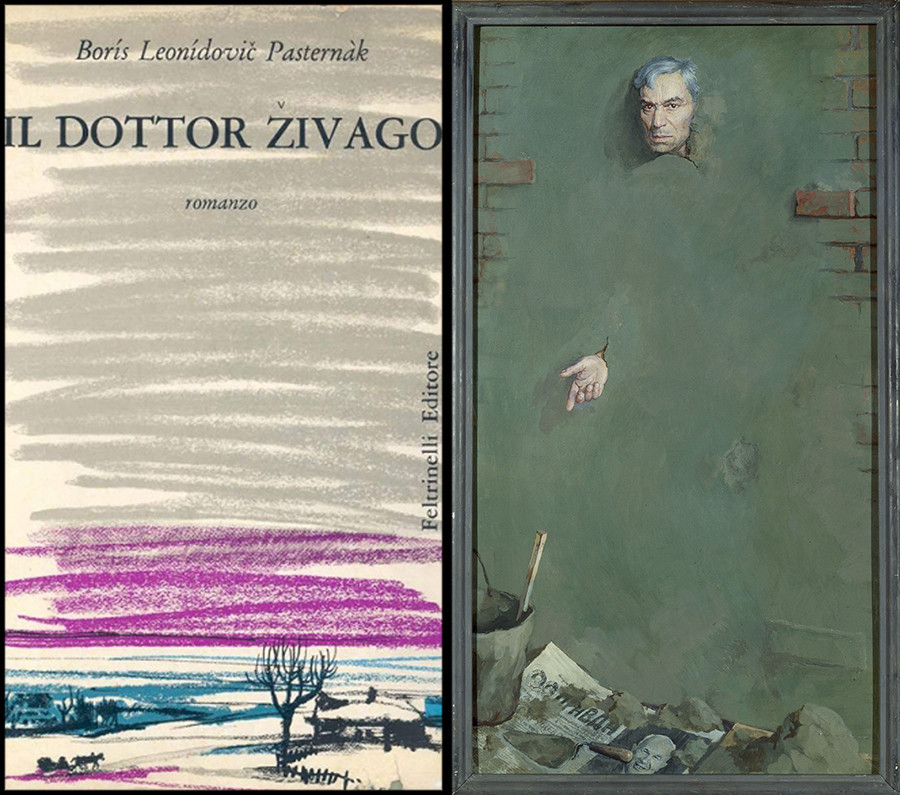

The book cover of the first Italian edition of 'Doctor Zhivago', 1957 (L) Petr Belov. Russian school. Portrait of Boris Pasternak,

Private collection; Getty Images; FeltrinelliPasternak managed to transfer the book to the West and, in 1957, ‘Doctor Zhivago’ was published in Italy. Later, the CIA revealed the documents that the agency was involved in bringing the book to light. It was their another propaganda “weapon” against the Soviet state.

In 1958, Pasternak was announced as a winner of the Nobel Prize in literature. The Soviet authorities became absolutely mad about the academy’s decision, perceiving it as a political step against the Soviet Union.

Omar Sharif as Doctor Zhivago

David Lean/Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1965A true bullying against Pasternak started in the USSR. He was announced a traitor and excluded from the Union of Writers, which, in those times, meant his work couldn’t be published at all anymore. Official Soviet authors arranged a whole bullying campaign. All official media wrote that the novel was slander of the revolution and the Soviet power. They quoted even some letters that proletarians allegedly sent to them condemning the novel.

But, the thing is that no one of them actually had a chance to read the novel. Because it was not published in the Soviet Union. So, many of these messages started with the words “I didn’t read Pasternak, but I condemn him,” or “I didn’t read this novel, but it’s bad.”

A meeting of Moscow writers

E. Ryapasov/MAMM/MDF/TASSParty committees, factories and institutes, had meetings where they collectively condemned Pasternak. Some people even suggested revoking Pasternak of the Soviet citizenship. Eventually, he had to publicly refuse his Nobel Prize.

The bullying campaign ruined the author’s health and he died of cancer in 1960. The novel was first officially published in the USSR in 1988.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox