Lydia Delectorskaya was born in 1910 into a cultured gentry family in Tomsk, but then she lost her parents at an early age. Another blow came during the Russian Revolution and her escape to Harbin in China. At that time, Harbin was a safe haven from the Soviet regime, and many Russian émigrés eventually settled there.

At the age of 20 she had a hasty marriage and soon moved to Paris. Rootlessness and divorce followed. A refugee with no rights, Lydia couldn't find a decent job and she tried her hand at many things: She worked as a film extra, dancer, and model. Two years later, in 1932, almost penniless, Lydia found herself in Nice…

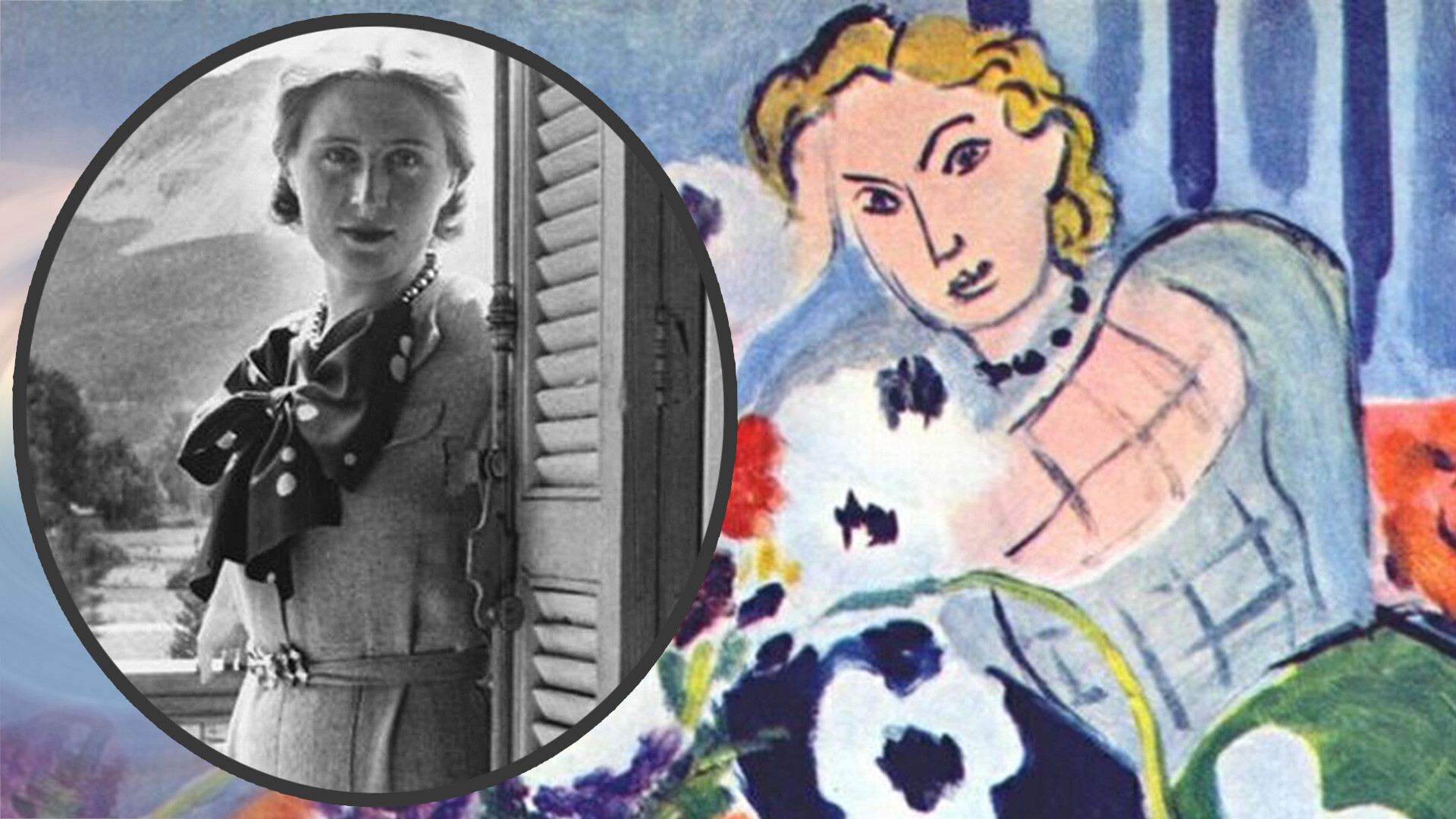

Lydia Delectorskaya portrait, published in her book "Henri Matisse: Contre vents et marées"

Editions Irus et Vincent Hansma, 1996This, in brief, was her life before she met Henri Matisse. Perhaps a few more details can be added to this life portrait. Lydia always had a passion for learning. When her parents were alive, she was home educated. Then she finished school in Harbin and enrolled at the Sorbonne in Paris, but she did not stay there for long because she couldn't afford the tuition. In a word, she was a well-educated young woman from a good family - qualities that largely determined how fate brought her close to the great French artist.

In 1932 Matisse was working on a new version of his legendary monumental canvas, The Dance, for a wealthy American, Albert Barnes. (The first version, painted by the artist in 1910, had been commissioned by Russian industrialist and art collector Sergei Shchukin, who discerned the artist’s genius that had been rejected by France).

The large-scale panel required more than one pair of hands, and Matisse was already over 60 at the time, so he desperately needed an assistant. Lydia responded to his job ad. Matisse later said that he employed her because the original Dance had been commissioned by a Russian. He saw it as a good omen for the future fate of the new panel.

When the work was finished Lydia was paid, and she began to pack her bags. But at this point Madame Matisse fell ill and needed a caretaker. The family decided to keep the dependable, quiet and cultured Russian.

True, it was precisely these qualities that soon backfired on the Matisses. Lydia proved to be not only a good caretaker but also an excellent housekeeper and secretary. While Madame Matisse was ill, Lydia gradually took over all of the artist's affairs.

Next, Matisse, who at first took no notice of the girl, suddenly looked at her with interest: He began to make sketches of her and made her sit for a portrait, and this continued for the next 20 years.

For a time the ambiguity of the situation was maintained in the family, but his wife's concern grew. Then, in 1939, Madame Matisse left her husband and filed for divorce. In the end, divorce proceedings were never set in motion but the family broke up. The spouses lived separately for the rest of their lives.

Lydia was often asked about the nature of her relationship with Matisse. She didn't evade the question but gave no straight answer either. It is obvious she didn't equivocate about one thing: Matisse, his talent and his work became the true meaning of her life.

For 22 years Lydia was everything to him. She looked after his business affairs and did his housekeeping, and when his strength began to fail him (the artist suffered in turn from asthma and arthritis, and in later years from cancer), she encouraged and comforted him, and championed his interests with collectors and art dealers.

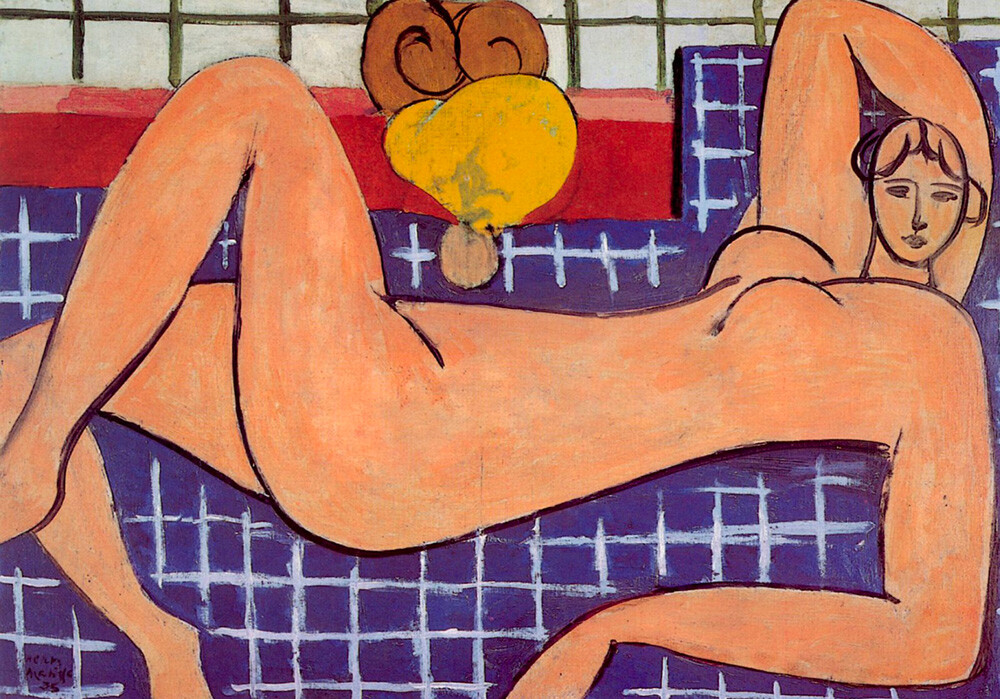

Henri Matisse. Pink nude, 1935

Baltimore Museum of ArtIn the war years, when they took refuge in the southern town of Vence, Lydia ensured there was enough food in the house and that he didn't freeze in the cold. Lydia is depicted in many of the artist's works. Experts count more than 90 paintings alone, among them The Pink Nude, 1935, several Odalisques of 1937 and Interior with an Etruscan Vase, 1940, as well as personalized portraits of Lydia that he made during these two decades.

Matisse got into the habit of presenting his muse with pictures twice a year. Not being a spendthrift, Lydia spent all the money she earned (the artist paid her a monthly salary as his secretary) on buying sketches and sculptures from him.

Immediately after World War II, Lydia contacted the Soviet diplomatic mission in France and sent an initial nine drawings as a gift to the land of her birth. The explanation she gave was that, as a Russian, she wanted her former countrymen to get to know the work of someone she regarded as the greatest artist of modern times.

Lydia subsequently enlisted the support of Soviet Minister of Culture Yekaterina Furtseva, and in the years of Perestroika she corresponded with museum directors and established personal friendships with them. Altogether, she presented more than 300 items to the Hermitage and Pushkin museums. It is largely thanks to her that the holdings of the works of Matisse in Russia today are the best in the world.

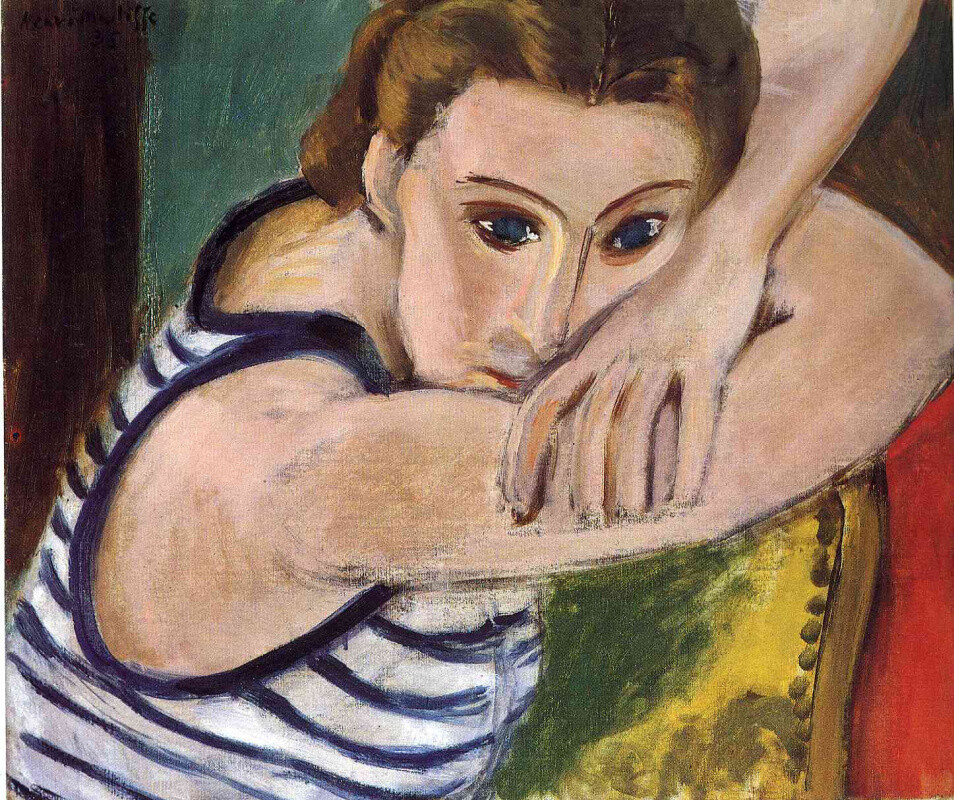

Henri Matisse. Blue eyes, 1934

Baltimore Museum of ArtIt’s remarkable that this woman who had left Tsarist Russia as a young girl wanted to return home, even though that home was now the Soviet Union. Despite her active collaboration with museums, she was politely refused a Russian passport during her lifetime. The authorities failed to give a specific reason, but it is easy to surmise that they were aware of Lydia’s gentry background and the fact that she had fled Russia in the years when the new Soviet state was established.

The disfavor with which she was regarded, however, failed to cool her ardor to tell the Russian people about Matisse, and the French about Russian culture. After Matisse’s death in 1954, his family dismissed Lydia. She left Matisse's home in Nice where the last two years of their lives had passed (today the villa by the sea is home to the Matisse Museum), and went to Paris, where she lived alone for almost another half-century.

Lydia wrote a number of monographs devoted to Matisse and played an active part in all kinds of activities to bring his oeuvre to a wider audience: from numerous interviews to the mounting of exhibitions and the setting up of the museum. Without selling the paintings he had bequeathed to her, she mainly lived off the royalties she earned translating from Russian into French, and vice versa.

In particular, she spent many years translating into French the works of Konstantin Paustovsky, whom she met in Paris in the 1950s. Thanks to the latter she eventually managed to visit the USSR - as his guest and at his invitation. She was able to proclaim quite justly: "I gave France Paustovsky, and Russia Matisse!"

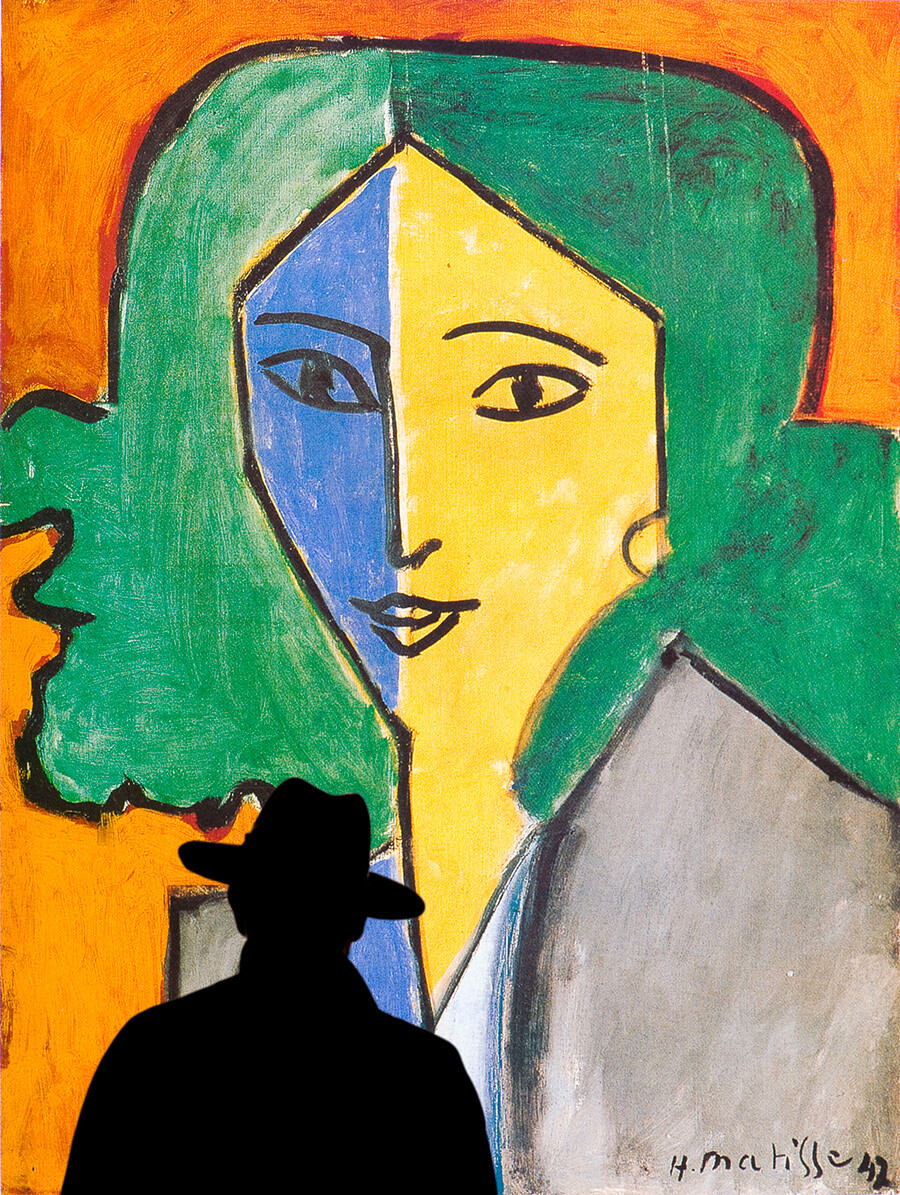

Portrait щf Lydia Delectorskaya by Henri Matisse, 1947

Legion MediaLydia died in 1998, aged 87, taking her own life. Without any hope of ever being buried in Russia in accordance with her last wishes, she purchased a plot in a Parisian cemetery and erected a memorial stone before she died, bearing words attributed, by legend, to Picasso: "Matisse preserved her beauty for eternity".

Nevertheless, Lydia's wishes were carried out by her niece and the remains of Matisse's muse were buried in Pavlovsk near St. Petersburg, next to a replica of the original stone.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox