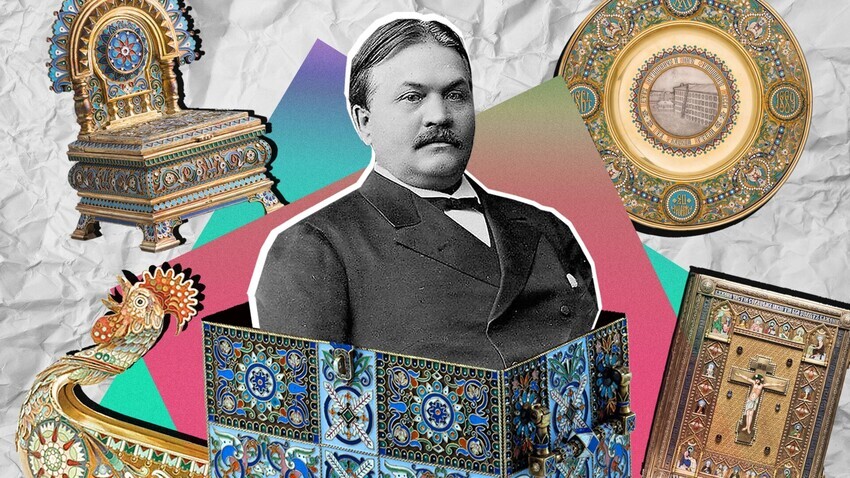

Pavel Ovchinnikov and his masterpieces

Kira Lisitskaya (Photo: Getty Images; State Historical Museum; Faberge Museum; Russian Museum)This is an amazing 19th century success story and an example of a truly brilliant career. Ovchinnikov was a serf owned by the princes Volkonsky. When he was still very young, his masters noticed his artistic abilities and sent him to Moscow to be trained as a jeweler.

Ovchinnikov did not only train as a goldsmith, but earned enough capital to buy his freedom and to open his own factory. He revolutionized jewelry making, revived the art of enamel, created a fashion for the Russian style and became a purveyor to the imperial court. That was how the Romanovs' collection was enriched with precious cigarette cases, goblets, sets, caskets and many other valuable items made by Ovchinnikov's firm. The jeweler also enjoyed recognition abroad: he was awarded a silver medal at Exposition Universelle in Paris.

Click here to read more about Pavel Ovchinnikov.

Praskovya Zhemchugova

A.A. Bakhrushin State Central Theatre MuseumCould a serf woman, a daughter of a Yaroslavl blacksmith, have imagined that a street in Moscow would be named after her? Incidentally, Zhemchugova was her stage name, while her real name was Praskovya Kovalyova. She became Count Sheremetev's property together with some land that he received as his wife's dowry and was raised at the count's Moscow estate in Kuskovo. As a seven-year-old girl, Praskovya displayed an aptitude for music and singing - she was taught the harpsichord and the harp as well as foreign languages so that she could sing opera arias in French. In the 1780s, Praskovya shone on the stage of the Sheremetevs' private theater, performing in Kuskovo and in their other estate, Ostankino.

Nikolai Argunov. Portrait of Nikolai Sheremetev

HermitageCount Nikolai Sheremetev fell in love with the beautiful actress and even asked Emperor Alexander I for permission to marry her. The request was something unheard-of at the time since many aristocrats had relationships with their serfs but no one considered marrying them. Having granted Praskovya freedom, Nikolai Sheremetev married her, and they had a son. Sadly, Praskovya died very young due to poor health.

Ivan Argunov. Portrait of Catherina the Great, 1762

Russian MuseumThe history of this talented serf family is also connected with the Sheremetev family. Ivan Argunov (1729-1802) studied painting with the German artist Georg Christoph Grooth, and they even worked together on the icons for the palace church in Tsarskoye Selo. Argunov became famous as a portrait master - he painted both private and official portraits of members of the nobility, and even Catherine the Great. One of his most famous paintings is the Portrait of an Unknown Woman in Russian Costume.

Ivan Argunov. Portrait of an Unknown Woman in Russian Costume, 1784

Tretyakov GalleryArgunov's two sons, Nikolai and Yakov, also became artists and painted portraits of famous persons and officials. Count Sheremetev granted both of them freedom, and they became members of the St. Petersburg Academy of Arts.

Ostankino estate of Sheremetev in Moscow

Vtorou (CC BY-SA 4.0)The third son, Pavel, became an architect and later was the chief architect of the palace theater in the Sheremetevs' estate at Ostankino.

Another representative of this talented family, Fyodor Argunov, was also an architect. He built half of the picturesque Kuskovo estate in Moscow, including the Grotto Pavilion and the Big Stone Orangery.

Grotto Pavillion in Kuskovo estate

Ulaisaeva (CC BY-SA 4.0)Fyodor also participated in the construction of the count's St. Petersburg palace, the Fountain House.

N. Nevrev. Portrait of Mikhail Shchepkin

Public domainToday, Shchepkin's name is immortalized in the official title of the Higher Theater School in Moscow, where he once taught and which is now named after him. The future great actor was born in the Kursk province in a serf family owned by Count Volkenshtein, and from childhood acted in his master's private serf theater. With his master's permission, Mikhail worked as a prompter in the city theater, which led to his invitation by theater companies in other provincial cities, where he was a great success.

Shchepkin played a variety of roles, including female parts. He began to develop his own acting method, with a particular emphasis on conveying characters' personalities and behavior as close to life as possible. It was his ideas that later formed the basis of the famous Stanislavsky system.

In the end, Shchepkin was invited to join the Moscow Maly Theater, where he played in the most popular Russian plays of the time: Denis Fonvizin's The Minor, Alexander Griboyedov's Woe from Wit and Nikolai Gogol's The Inspector General.

Orest Kiprensky. Self-portrait (L), 1828 / Girl wearing the poppy wreath, 1819

Tretyakov GalleryOrest Kiprensky, who became popularly known as "the Russian Van Dyck", was the illegitimate son of landowner Adam Diakonov and his serf. Unable to officially recognize the child, the father listed him as a member of his serf mother's family.

From childhood, Orest showed a talent for drawing, so his father enrolled him at the Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg. The Academy's administration spotted the talented young man, allowed him to live in the Academy's boarding house after graduation and granted him an allowance for a trip abroad.

Orest Kiprensky. Portrait of Alexander Pushkin, 1827

Tretyakov GalleryIn Italy, a portrait he painted was placed in the Uffizi Gallery, while one of his works was even mistaken for a Rembrandt. Furthermore, Kiprensky is the author of arguably the best-known portrait of the poet Alexander Pushkin and of other familiar portraits of many of his great contemporaries.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox