Even in childhood, the relentless woman carried the nickname ‘Nadia the Cossack’ for her daring spirit and bravery. Nadia Khodasevich was born in 1904 into a poor family in a village outside Vitebsk. Her father was a vodka salesman and her mother was a weaver, who raised nine children. The family lived a peasant life. Nadia recalled spending entire days in the vegetable garden, shoveling potatoes. She would spend the nights drawing - the girl was talented and, already as a child, harbored ambitions of becoming an artist.

In her teenage years, an article in a newspaper about Paris caught her eye. It presented the city as a place where all the artists moved to. This led to a decision to run away from home and hitchhike it all the way to Paris. However, she was recognized at the next train station and sent home.

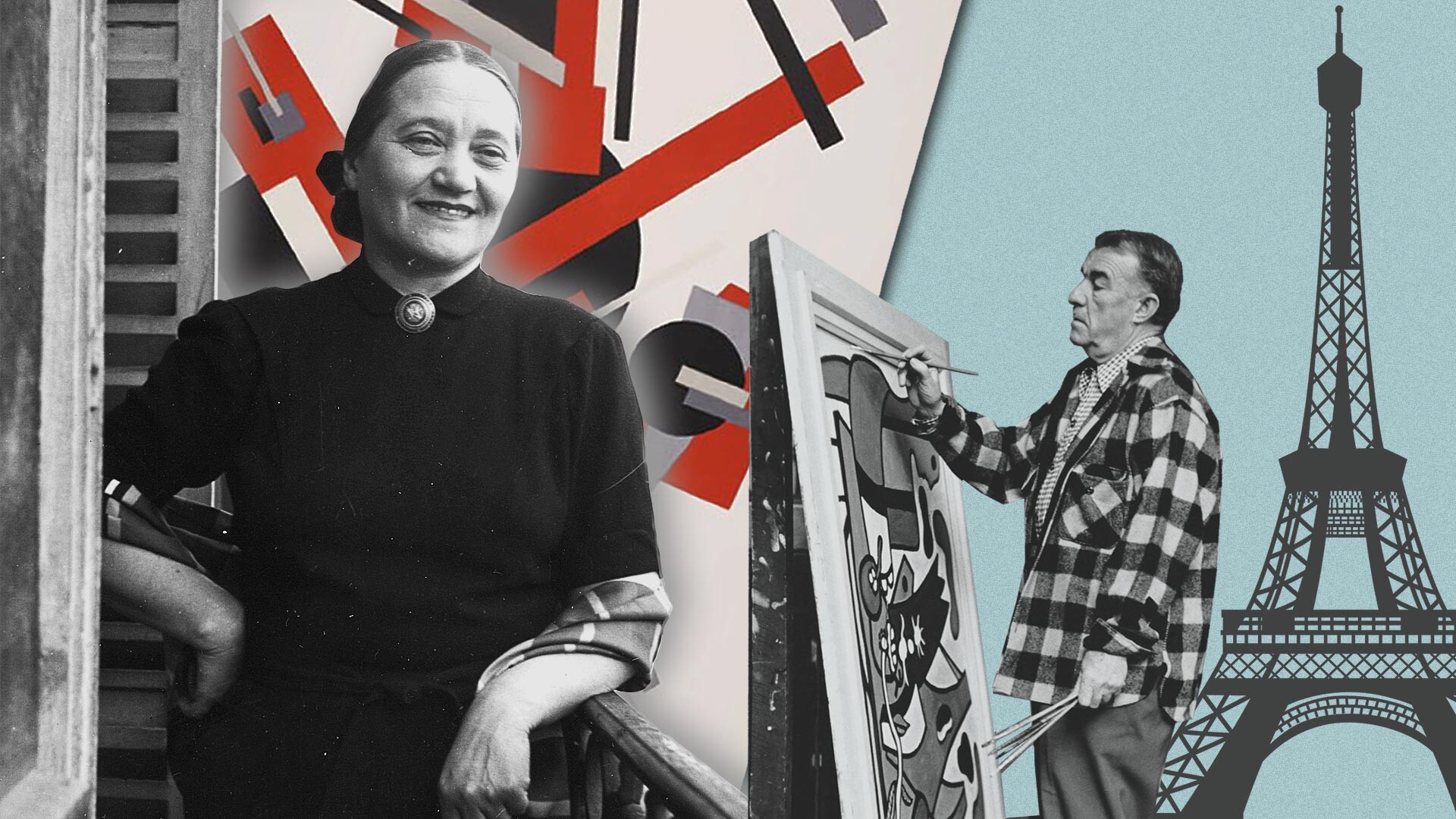

Nadia Léger

Nathalie Samoïlov (CC BY-SA 4.0)At the start of World War I, the family moved around a lot and Nadia’s first artistic education would be received in an art class in the countryside. At 15, she ran away again - this time, to Smolensk, where “free state artistic workshops” were all the rage. One such workshop immediately took the gifted, self-taught young girl in. For a considerable amount of time, she’d lived on “bread and water”; until her teachers gave her a place to sleep, she used an old carriage on the train station’s reserve tracks as her quarters.

Nadya’s first works were purely abstract. After meeting Kazimir Malevich, however, she transitioned to suprematism. Later, having evolved into an avant-garde artist, she moved to Europe, starting with Poland, but always kept her eye on the target - Paris.

Nadia Léger. Suprematism, 1972-73

Pushkin Museum of Fine ArtsAt one point, she remembered her father’s Polish roots and converted to Catholicism, using her refugee status to take up residence in Warsaw in 1921. There, her objective was to pass the selection and be admitted to the Academy of the Art. That did little to change her living conditions however: First, there was a foster home, then a stint as a live-in nanny and then, when she began her studies, she supplemented as a milliner at a headdress atelier. The woman always stood out thanks not only to bravery and the thirst for adventure, but also to a phenomenal work capacity. She later recalled requiring only an hour of sleep as a child without once feeling tired the following day.

A new chapter in the future Mrs. Leger’s life was the long-awaited move to Paris. Her first husband, Stanislav Grabovsky, was also a student at the Academy. He came from a rich family and the young couple wanted for nothing in Paris. In 1942, the pair enrolled together into another artist academy, founded by Nadya’s hero and future husband - Fernand Leger. She would later recall reading about him for the first time in a newspaper at the turn of the century, by which point suprematism had lost its grip on her and her next artistic path was still unclear. It was precisely Leger’s visual aesthetic - his promotion of the return to form - that opened her up and gave her a new base to work with.

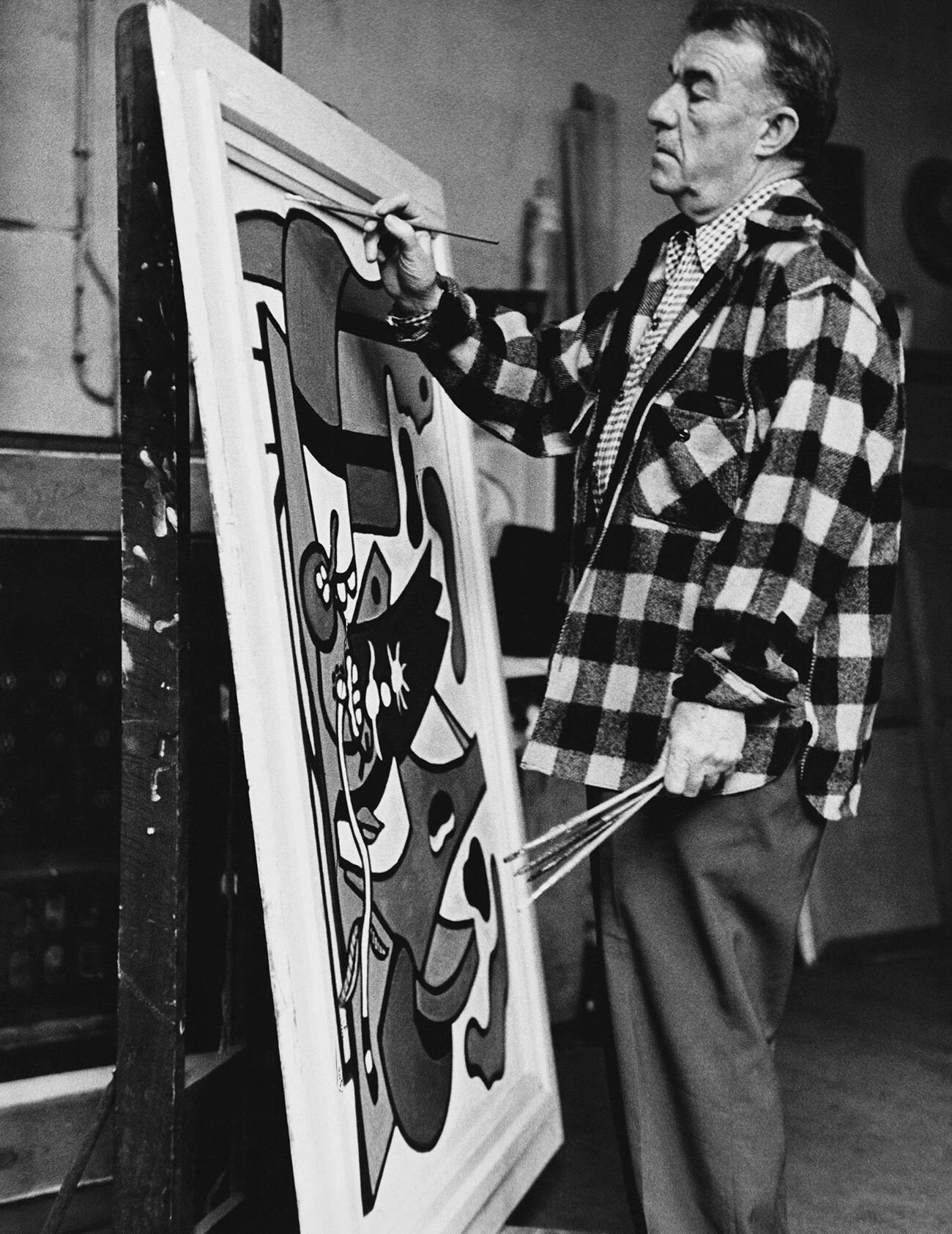

Fernand Léger

Legion MediaIn Paris, Nadia did not only study, but immediately began making friends in the art world and selling her works, which soon resulted in some pretty substantial income. The husband wasn’t as successful and this led to arguments between the two, ending in divorce. Nadia was left with a small daughter and became a journey-worker again: first, she was a maid at a health resort - one she’d used to book the best rooms in before. But, despite the uneasy circumstances, she continued to study hard and even found time to use her scant earnings to publish a magazine on modern art.

In 1939, on the eve of World War II, Fernand Leger offered the talented student a job as his personal assistant. The creative union was postponed by the fact of the war, however. Leger, who was a member of France’s communist party and a regular appearance on fascists’ blacklists, emigrated to the United States and came back only in 1945. Nadia, meanwhile, remained in Paris. Influenced by Leger, she also enlisted into the communist party and went underground when war broke out, working for the French Resistance. She later even claimed to have owned a small gun, although her main job had been creating propaganda materials.

Fernand Léger. Portrait of Nadia Léger, 1948

Pushkin Museum of Fine ArtsUpon Leger’s return, Nadia finally took her place by his side. She also continued to create. Her favorite genre was portrait painting, which took on the style of postwar expressionism seen in David Siqueiros’s works.

Leger’s wife of 30 years passed away in 1951. A year later, he proposed to Nadia. By then, he was already 70, while Nadia was 20 years his junior. Lager’s final years would be spent together with Khodasevich - who was then Khodasevich-Leger.

The French artist passed away in 1955, with the marriage having lasted only three years. Fernand still claimed he was never happier. Nadia, meanwhile, was left with a sizable inheritance, her days of poverty now behind her. Aside from the money and several homes, Leger left behind a colossal artistic legacy, which Nadia would create a museum in the south of France with, in a place called Biot, where, not long before Fernand’s passing, the family bought a small country home.

Fernand Léger. Reading (portrait of Nadia Léger), 1949

Pushkin Museum of Fine ArtsNadya spent the remainder of her life popularizing Leger’s art, including in the USSR, which was fond of Fernand for his leftist worldview.

Nadia Léger, 1964

Reporters Associes/Gamma-Rapho/Getty ImagesImmediately after the war, Nadia enlisted in the Union of Soviet Patriots, which linked together Russian emigrants in France. In 1945, under the union’s aegis, she initiated a charity exhibition, consisting of contemporary artists - including Leger, Braque and Picasso - in order to gather proceeds for former Soviet prisoners of war. After her husband's death, thanks to her relationship with the French communst party elite, she forged ties with Russian “colleagues”, including the Minister of Culture, Ekaterina Furtsova. In 1959, she would visit the Soviet Union for the first time to begin actively promoting the cultural exchange between the two countries. This would air her reputation during the years of the Thaw, with Russian society looking favorably on her work.

Pictured L-R: Nadia Léger, Soviet Minister of Culture, Ekaterina Furtseva, and Soviet ballerina Maya Plisetskaya in Moscow, 1968

Alexander Konkov/TASSIn 1963, she held her first monographic exhibition in Russia, consisting of Leger’s works, which she would later organize into more exhibitions. Back in the West, she continued to promote Russian writers and film directors (including Konstantin Simonov, whom she was close friends with). In 1972, Khodasevich-Leger was awarded the Order of the Red Banner of Labor “for the contribution to the development of Soviet-French cooperation”.

The National Arts Museum in Belarus contains many of Nadia Leger’s works, which she donated in 1967 to pay homage to her roots. Aside from that, the Kremlin’s museums contain a collection of her gold, platinum and diamond jewelry, donated in 1976.

Nadia Léger. Lune brooch. 1970

Moscow Kremlin MuseumsFurthermore, visitors will be treated to her mosaics in Dubna, Moscow Region: they were used to decorate the alleys near the scientific town’s two local culture centers. The mosaics constitute a series of portraits of prominent Russian scientific and cultural figures.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox