As a still life master and academician of the Empire Academy of the Arts, Khrutzky always kept to the artistic traditions of old European masters - his work closely resembling 17th century Dutch still life.

The artist himself opted to name the work ‘Unwelcome Guest’ - its entire meaning hidden in a small detail: that of a barely covered and poor breakfast meal consisting of a piece of black bread. This stands in stark contrast to the picture of aristocracy that the young man so wished to convey.

The work depicts a feast in honor of uniting two boyar clans - a very important event for any old-Russian elite. Roasted swan is being brought out - a traditional meal at a boyar wedding, symbolizing fertility.

During a period of creative self-searching, the famous avant-garde artist tried his hand at the French style of cloisonné, which features large blots of color enclosed in thick straight lines.

Serebryakova is one of the few women in Russian painting preferring to touch on family scenes - specifically, portraits of her children, one of which contains a family breakfast. Herself coming from a bohemian, creative upbringing, her household has retained European gastronomic traditions: in the morning, there was a small breakfast, followed by a filling brunch in the afternoon.

An avid fisherman, Korovin frequently appealed to the theme of “fish still life”, done in his beloved impressionist style. The painting - if we are to go by the colors - can be classified as “Korovin nocturnal still life”.

With the advent of the Bolsheviks, the years of private trade had become a thing of the past. Here, Kustodiev uses the image of the voluptuous woman with a rich pedigree, living in luxury - a samovar in front of her, surrounded by exquisite china and delicious food - as an image of Russia that had by then been consigned to memory. In those years, financially destitute and crippled by illness, the artist wrote the opposite of what we saw on his canvases: “Life is really not good for us here, it’s cold and we’re hungry. All one can hear about these days is food or bread…”

“We’ve grown really hungry over the summer, [it] feels like we’re animals, food is the only thing on our minds.” These lines were penned by the artist in November 1918, at almost the same time as he created his still life work, which depicts all too well the basic diet shared by everyday people at the dawn of the Soviet era - dried-up herring, a stale loaf of bread and several potatoes.

Picturesque illusionism in still life made a return in the 1930s. A decade after widespread famine gripped Ukraine, Kuban, the Povolzhye and Kazakhstan, millions lost their lives. Meanwhile, officious still life continues to depict a veritable grocery utopia: ears of corn made of dough, baked goods of all shapes and sizes, boggling the mind - all staying confined to the imaginations of most mortals.

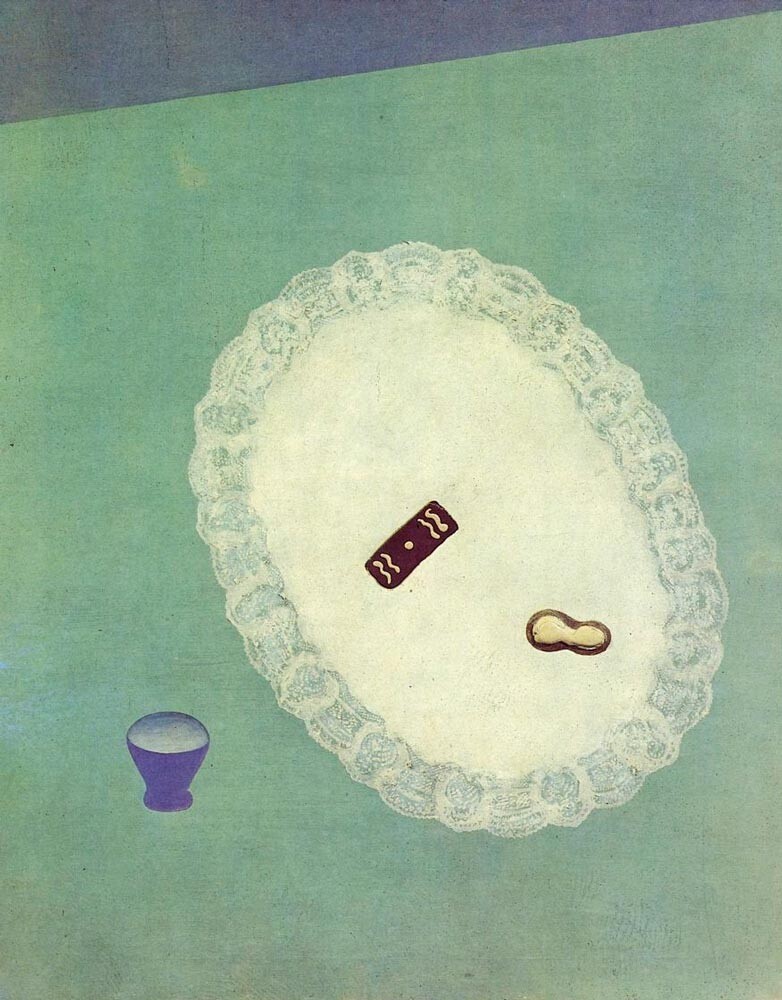

The ascetic still life of Sternberg’s was far closer to reality than many works listed here. The tiny cake on a disproportionately large plate conveys the sense of unobtainable luxury in the post-revolutionary years.

Writer Aleksey Tolstoy would visit Konchalovsky at his village estate, with the latter depicting the former sitting at a lavishly set Russian table: sumptuous ham, incredibly thin-sliced petals of red fish, roasted partridges, crispy cucumbers, red tomatoes, a bright-yellow, juicy lemon and various drinks. A fantastic feast that anyone in those days would have loved to enjoy.

Another example of social realism in still life, the painting, with all its pickles, preserves and cans would have looked like the definition of abundance to folks in the 1930s. The artist was tasked with evoking a sense of wealth and satiety in the audience of a “great country”.

The great master of Soviet impressionism, Yury Pimenov, depicts the breakfast of a Soviet man in the 1970s. It's not an ordinary set of products (still quite chic), but it's already close to the reality of its time.

The Abramtsevo estate is referred to a "place of power" of Russian artists, and the birthplace of Russian Art Nouveau.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox