Director and actor Nikita Mikhalkov, winner of the Best Foreign language Film Oscar from his movie "Burnt with the Sun", and his daughter Nadya, who appeared in one of the lead roles in that movie, holding Oscar figurine

M.Gnisuk/SputnikDue to the Cold War when Russia was cut off from the West by the Iron Curtain, Soviet films had a limited presence at film releases abroad and rarely found their way to prestigious festivals. During Perestroika in the late 1980s and up to the mid-1990s, an unprecedented wave of interest in Russian cinema swept the world - but even then it rapidly subsided.

Despite the difficulties, a number of Soviet and Russian films still managed to cross the East-West divide and earn the admiration and acclaim of cinema professionals. Here is a list of the most prestigious international awards in the history of Russian cinema.

Director Sergei Bondarchuk's masterpiece, “War and Peace” - a colossal 6-hour epic based on the novel by Leo Tolstoy - was the first Soviet film to receive an Oscar nomination for Best Foreign Film (1969). And the Soviet Union was successful at its first attempt!

“War and Peace”

dir. Sergei Bondarchuk, 1965/MosfilmOddly enough, the USSR acquired its second statuette in 1976 thanks to the great Japanese director Akira Kurosawa. “Dersu Uzala”, a screen version of the memoirs of the traveler Vladimir Arsenyev, was the director's only film made outside Japan.

“Dersu Uzala”

dir. Akira Kurosawa, 1975/MosfilmVladimir Menshov's “Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears” - a winner in 1981 - is considered the most ‘American’ of Soviet movies. Before it won over the academy of film in the U.S., this story of a young woman from a small provincial town who climbs the corporate ladder from ordinary worker to factory director captivated Soviet audiences. With about 90 million theater tickets sold, it was one of the biggest box-office successes in Soviet film history.

“Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears”

dir. Vladimir Menshov, 1979/MosfilmFinally, the only post-Soviet era Russian film to win an Oscar was Nikita Mikhalkov's “Burnt by the Sun” (1995), which shows a day in the life in the 1930s of a Soviet komdiv (army divisional commander) played by the director himself. The main protagonist is shown relaxing at his dacha and enjoying himself unaware that he’s destined to be one of the first victims of Stalin’s purges.

“Burnt by the Sun”

dir. Nikita Mikhalkov, 1994/Trite studioIt’s been a longstanding unofficial tradition that Venice is the most russophile of international film festivals. Soviet and Russian films have frequently been featured in the competitive parts of the festival and have been awarded prizes. The list of winners of the grand prize at Venice includes a fairly representative selection of the great works of Soviet and Russian cinema

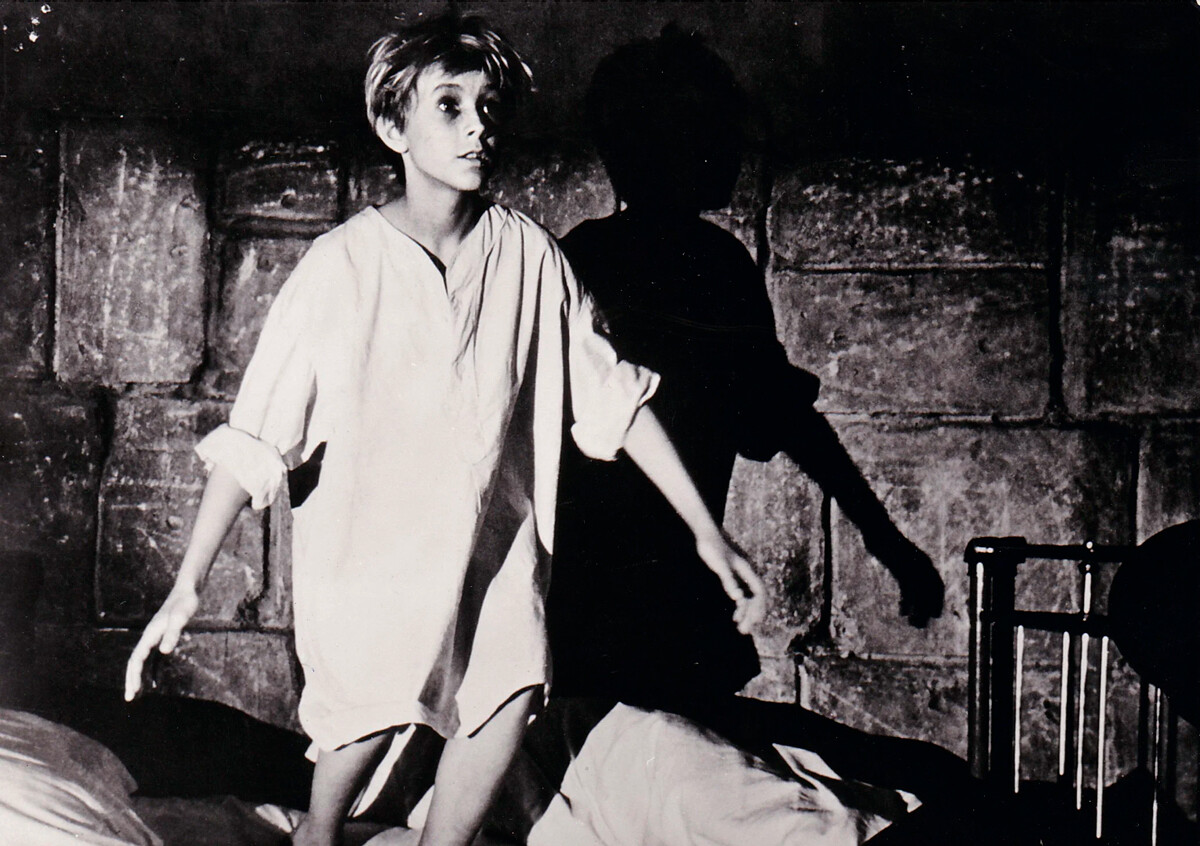

In 1962, Soviet director Andrei Tarkovsky was the first to bring home a Golden Lion when he found success with his very first film, “Ivan's Childhood”, which is the story of an orphaned boy who becomes a reconnaissance scout during the Great Patriotic War.

“Ivan's Childhood”

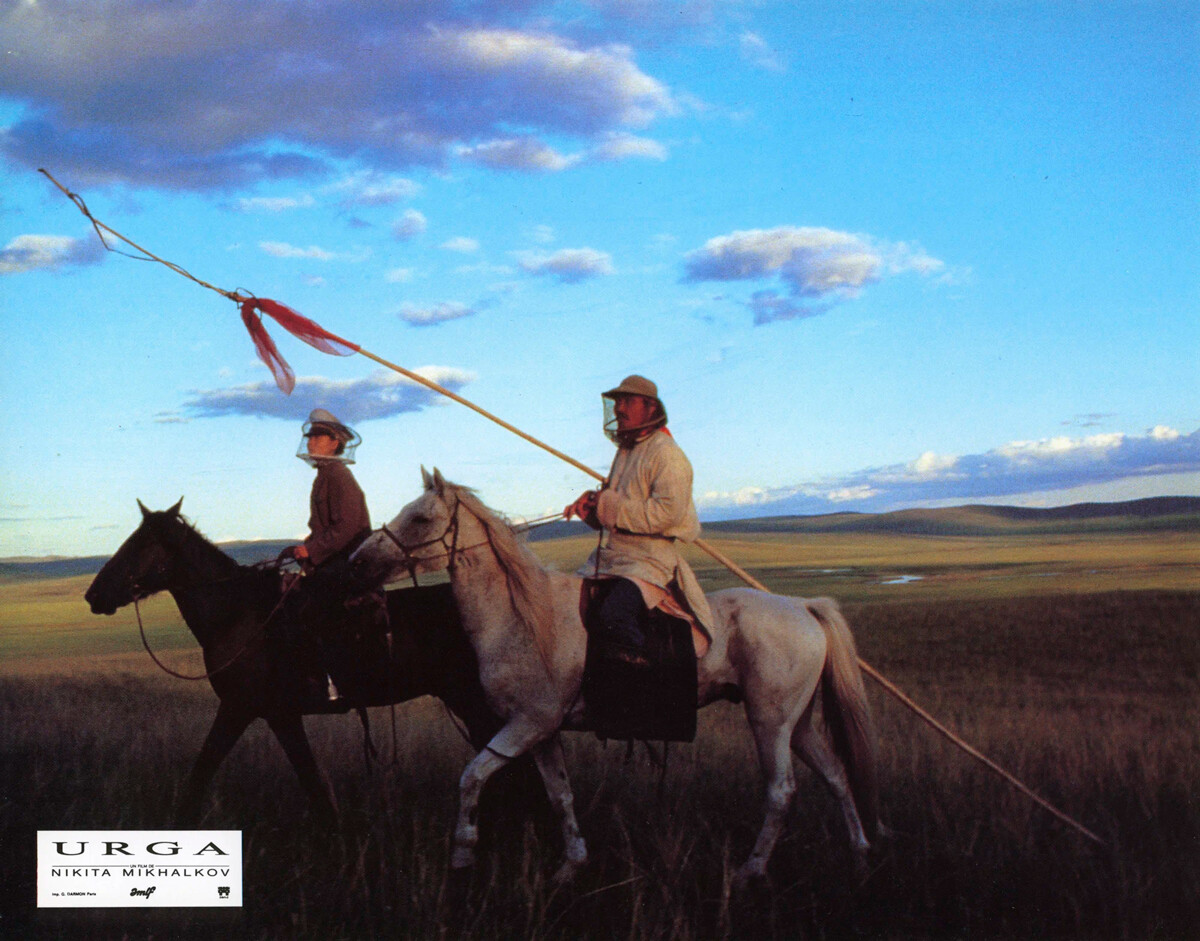

dir. Andrei Tarkovsky, 1962/MosfilmThe second Russian winner at Venice was Nikita Mikhalkov in 1991 with his tragicomic parable about the friendship between a Mongolian shepherd and a Russian truck driver, “Urga - Territory of Love” (released in North America as “Close to Eden”).

“Urga - Territory of Love” (a.k.a. “Close to Eden”)

dir. Nikita Mikhalkov, 1992/Trite studioAs had happened with Tarkovsky in 1962, Venice made an instant international star of another debut director from Russia - Andrey Zvyagintsev. In 2003, his cinematic parable “The Return”, which is about a journey that a father takes with his two sons, ending with a tragic denouement, surprisingly took not just the main prize but also Best First Film. This was the first time that both awards, which are judged by different juries, ended up going to the same director.

“The Return”

dir. Andrey Zvyagintsev, 2003/Ren filmFinally, in 2011, Alexander Sokurov - one of the most brilliant and uncompromising directors of art house cinema - won the grand prize for his screen version of Goethe's play in verse, “Faust”. The cinematography in “Faust” was by Bruno Delbonnel, who also shot “Amélie” and “Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince”, and who has worked with Tim Burton and the Coen brothers.

“Faust”

dir. Alexander Sokurov, 2011/Proline FilmLarisa Shepitko's “Ascent” - the 1977 winner in Berlin - is another parable clad in the trappings of a war drama. This film tells the story of two partisans who were taken prisoner by the Germans during the Great Patriotic War. They are given a choice - either collaboration with the enemy or death. The movie was the last in the career of the talented female director; two years after her Berlin triumph Shepitko died in a car crash.

“Ascent”

dir. Larisa Shepitk, 1976/MosfilmExactly 10 years later, the Golden Bear again went to a Soviet director, Gleb Panfilov, who won the award for “The Theme” - a tragicomic drama about a popular and officially approved playwright who faces a creative crisis. The movie was finished in the late 1970s, but it "sat on the shelf" for seven years (to use the Soviet idiom signifying that it was banned by the censor), and only reached the screen during the period of Perestroika.

“The Theme”

dir. Gleb Panfilov, 1979/MosfilmStrangely enough, Soviet/ Russian cinema has only earned one grand prize at the Cannes Film Festival. The 1958 Palme d'Or was won by Mikhail Kalatozov's melodrama “The Cranes Are Flying”, which is about a girl who is waiting for her boyfriend to return from the front during the Great Patriotic War.

“The Cranes Are Flying”

dir. Mikhail Kalatozov, 1957/MosfilmThe jury was won over not just by the fine performances (with one French critic comparing actress Tatiana Samoilova to Brigitte Bardot), but also Sergey Urusevsky's innovative camera work. In spite of the antiquated technology, he managed to achieve exceptionally fluent and free camera movements.

In 1964, Kalatozov and Urusevsky released another joint work, “I Am Cuba” - an anthology of short stories about how life had changed on the "Isle of Freedom" after the victory of Castro’s socialist revolution. The film did not end up with any major awards, but years later it came to be critically acclaimed and widely recognized.

In various rankings of the best films in cinema history, “I Am Cub” features more frequently than “The Cranes Are Flying”. Western fans of Kalatozov’s and Urusevsky's film about Cuba include Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola, who personally financed the film’s restoration.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox