They'll never die: WWII and the eternal legacy of our grandfathers

A WWII veteran attends a Victory Day military parade in Moscow's Red Square, May 9, 2015.

Marina Lystseva/TASSEvery year there are fewer and fewer WWII veterans available to take part in the Victory Day celebration in Russia. They are constantly leaving us and now there is practically no one left who can tell us about the war.

However, paradoxically, the events of those years, which are reflected in an endless number of lives, stay behind, that is, they remain with us. In Russia you still cannot find a family that has not been affected by that war. The memories are passed down from generation to generation and you can still feel the history as if it was there in front of you.

Yet what's interesting is that all of these household war stories never contain battle scenes or chest-beating patriotic elements. They are all about one thing: about real human qualities and the greatness of the spirit of ordinary people when facing death and pain, when your own pain and death are lesser than those of others.

Today the RBTH editors, themselves a rather young bunch, speak about that small piece of common history that they have inherited.

Anna Sorokina, 29

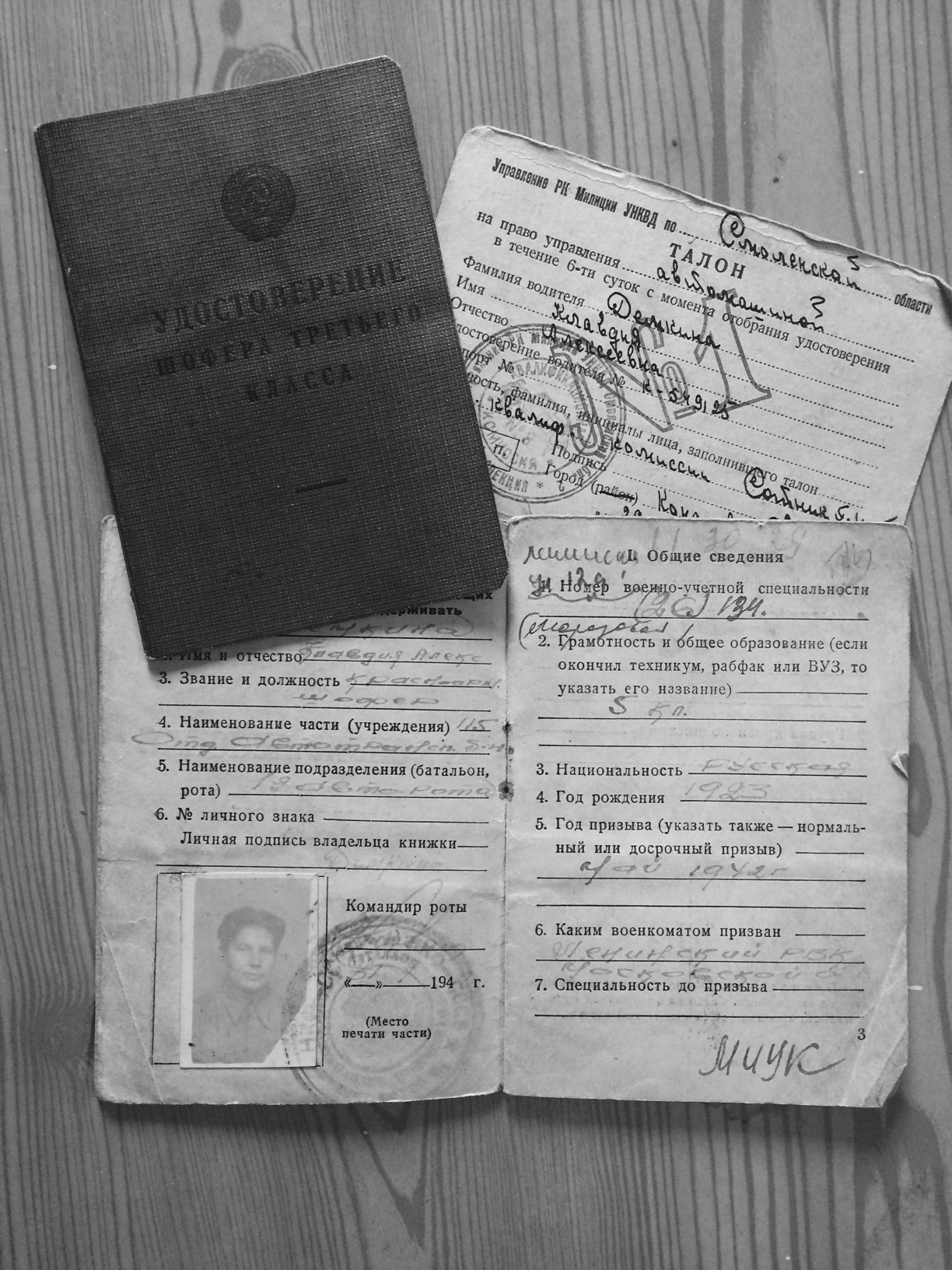

Each year, right up to her death, my grandmother Klavdia Morozova waited for the Victory Day celebration. She had saved and would constantly reread all the congratulations postcards sent by the Moscow Region Administration. "Ah, they haven't forgotten again." On May 9 she would take out her jacket and medals and would prepare herself for the local Victory Day parade.

She had lived her entire life in a small village near Moscow and when the war broke out, her brother Vasily was one of the first people who were sent to defend the capital. He died immediately, in July 1941 ("a brave death," as it was written). Then, in the fall of 1942, she and her sister also received draft notices.

She would tell us that she had come home before anyone else that day and seen two notices. At the military commissariat she asked the authorities not to take both sisters, since she had a mother (her father had died in 1939) and three little children, and there was no one who could take care of them. There was only her brother's widow, who had little children of her own. "Fine," said the official, "then we'll take you since you're so proper."

The following day she came to the assembly point with her things. She had not told anyone that there were two notices. She was sent to a three-month driving course and then, immediately after the exams – to the front. She found herself in Smolensk, not far from the border. Her group would transport fuel to the airplanes, and the airport was often bombed.

"It was scary and we all really wanted to live," she would later remember. One of the bombings covered her with earth and afterwards she regained consciousness in a military hospital called Burdenko. She underwent a trepanation operation and spent half a year in the hospital room. Then she was sent home, with a loaf of bread and a piece of soap. She said that she was really hungry, but brought everything to her mother. For the remainder of the war she contributed to the defense of Moscow: Not far from the village was an anti-aircraft defense battery. There she met her future husband, the battery's commander.

She would say that while she had been lying in the ground the Mother of God visited her and told her that she had to live. Since then there would always be an icon of the Mother of God of Smolensk near her.

DariaStrelavina, 22

I know my great-grandfather Anatoly Kolyzhev only through my grandmother and mother's memories.

Just a couple of days before the beginning of the Great Patriotic War [the Russian term for World War Two – RBTH], at the young age of 17, he arrived in Brest, in Belarus. Early in the morning of June 22, 1941 the German fascist troops began a massive bombardment campaign of the Brest fortress, the siege of which signifies the beginning of the war on Soviet territory.

The Brest fortress, Belarus. Source: Lori / Legion Media

The Brest fortress, Belarus. Source: Lori / Legion Media

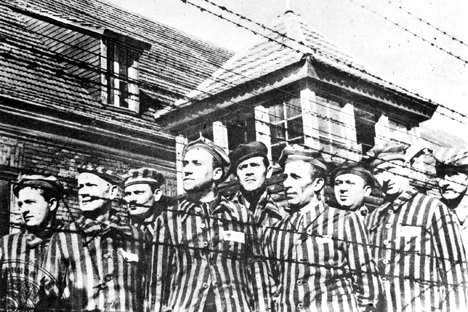

My great-grandfather was wounded in this battle. He lost consciousness and awoke in a concentration camp. Captivity was the tragic fate of hundreds of thousands of WWII soldiers.

Those who remained alive had to go through terrible hunger, forced labor, beatings and other unthinkable experiences. My great-grandfather went through the Majdanek Third Reich death camp (Majdanek, Poland) and the Nazi Dora-Mittelbau camp, a subdivision of the Buchenwald death camp in Germany.

In one of the camps he and his friend decided to escape. The attempt was unsuccessful. His friend blew himself up on a mine and dogs caught up with my great-grandfather. He would remember how hard he was beaten after that attempt. He also remembered how the military warden secretly fed him with potato peels and the leftovers from the German soldiers.

In 1944, as the German troops were retreating, they decided to eliminate the concentration camp. They lined up all the POWs, turned on the crematory furnaces and began burning people.

"I took a handful of earth, clenched it with my fist and started saying farewell to this world. Suddenly near the camp we hear a cannonade from our comrades-in-arms. We then jumped on the Germans and fought with them hand to hand!" my great-grandfather would say, remembering that horrible episode.

Kira Egorova, 27

For many people of my generation May 9 is a day of memories that were passed down from our parents, since it was our great-grandparents' generation that went through the war.

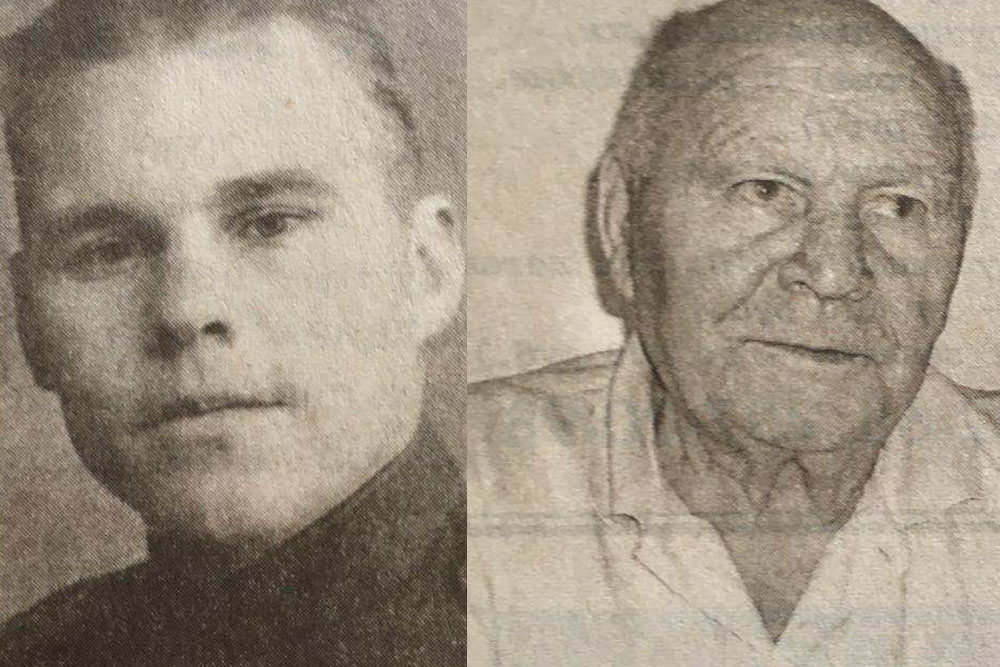

My great-grandfather Nikolai Egorov served in WWII from 1941 to 1945 as a military driver. He was born in the town of Kuznetsk, in the Penza Region, where my parents still live. In 1938, when Nikolai turned 20, he obtained his driving license, an achievement that was comparable to flying to space. At that time there were only three people with a driving license in Kuznetsk and my great-grandfather was one of them.

Nikolai Egorov (right). Source: Personal archive

Nikolai Egorov (right). Source: Personal archive

At the beginning of the war on Soviet territory Nikolai was drafted and sent to drive military cars at the front. In the winter of 1942 he drove back and forth along the Road of Life – he transported bread and provisions for besieged Leningrad right on the ice of Lake Ladoga.

In 1945 Nikolai Egorov was part of the Soviet offensive that reached Berlin and he also received a medal for the conquest of Vienna. After the war he returned to Kuznetsk to his wife Tatyana and son Yevgeny, my grandfather, and continued his work as a driver. Nikolai lived to be 70 and died in 1989, when I was only a few months old.

Alexandra Guzeva, 25

No one fought in the war among my great-grandfathers. But the war is inextricably linked to every Russian in the country and in one way or another affects his or her life.

When I was still in school and working for a small newspaper in one of Moscow's neighborhoods, I was given an assignment to write about a war veteran, Alexander Gureyev, who lived on our street. I had expected to meet a frail old man, but he turned out to be vigorous and full of life, laughed a lot and laughed even at himself. He headed the local veterans office. Despite the fact that the wound in his leg still made itself felt, every May 9 he would attend the victory parade on Red Square. "We get together, meaning the Germans didn't put an end to us, and remember our youth," he joked.

He had been through the Battle of Kursk and reached Berlin, having served in the artillery. He remembered that it was particularly frightening to be on the narrow European streets, where shots were coming from everywhere and he had to aim and shoot in retaliation.

Maria Azhnina, 29

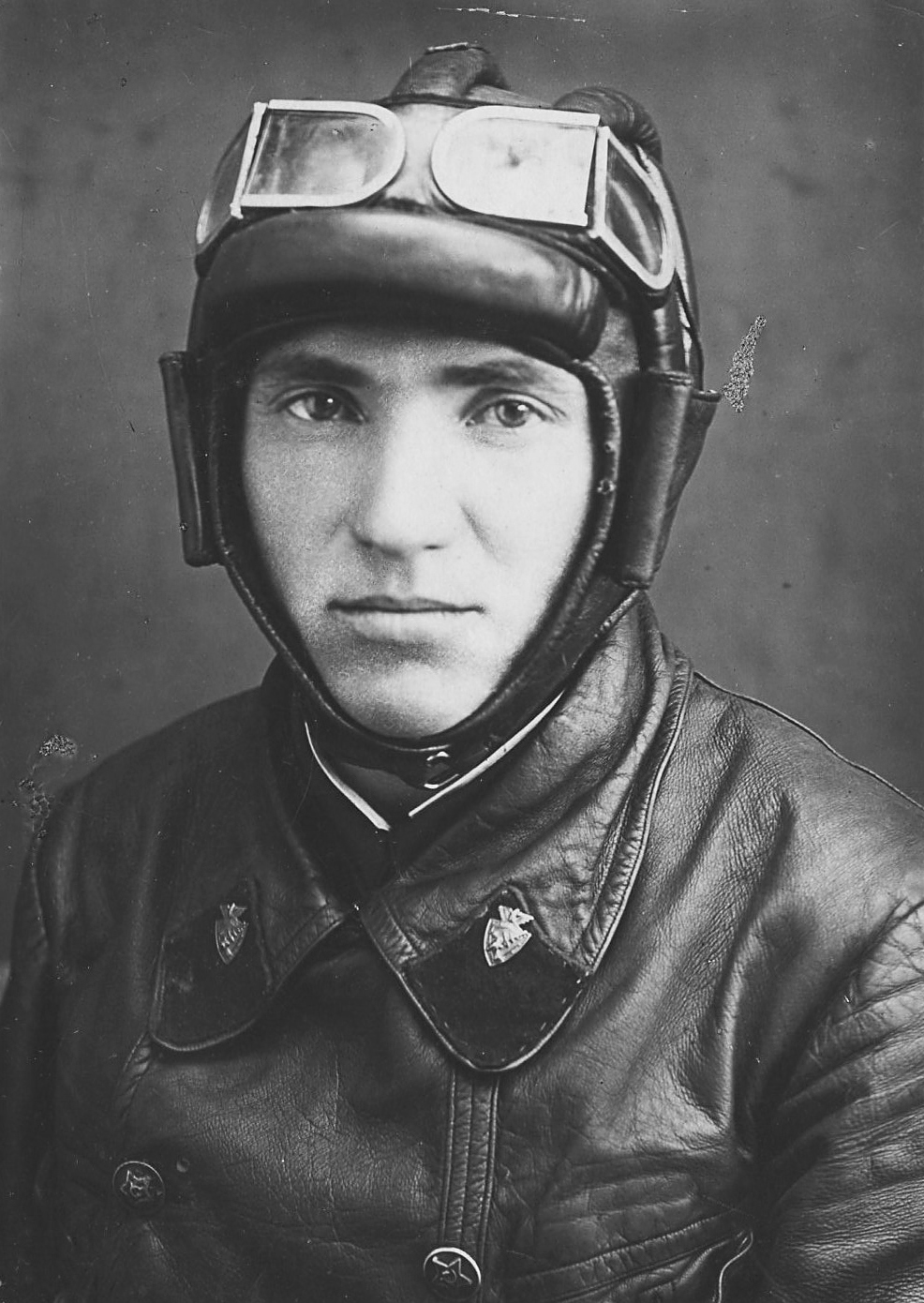

As part of the famous 5th Dvinsk tank division my grandfather Alexander Azhnin reached Berlin and was awarded Patriotic War medals of the second class, the Red Star and the Medal of Valor. He spoke with his friends and family about the war years in simple terms: "I did what I had to. What else?"

My grandfather is no longer alive but I know his story from my grandmother, Lyudmila Azhnina. She left for the front as a volunteer when she was 17, having lied about her age. Her surname was still Smirnova. She was deployed to a hospital train and she had to get used to her fear of the sky: The fascist planes would fly right over the train and bomb it, aiming at the bright red crosses on the wagon roofs.

It is painful for my grandmother to remember whatever is related to death and fear. More often she talks about ordinary stories: how everyone would sing and dance during the stops when there was no shooting; or how she wrote home: "Sell everything, just so there is enough to buy food!"

Once they were transporting the wounded criminal prisoners who had been sent to the front. At the railway station one of them robbed a person being evacuated. My grandmother approached him: "How can you do this! These people are poorer than you, they don't have homes, they don't have anything!" "I screamed at them," she would remember, "at these hardened criminals and my fear went away. I did it for honesty's sake!" "Sister, sorry, we'll return everything." And they did.

My grandmother is 92. Her Patriotic War medal of the second class is brighter than my grandfather’s. She received it later. But any honor and any type of glory fade in comparison to the fact that thanks to them I and everyone else are alive today.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox