Was British spy Somerset Maugham sent to kill Lenin?

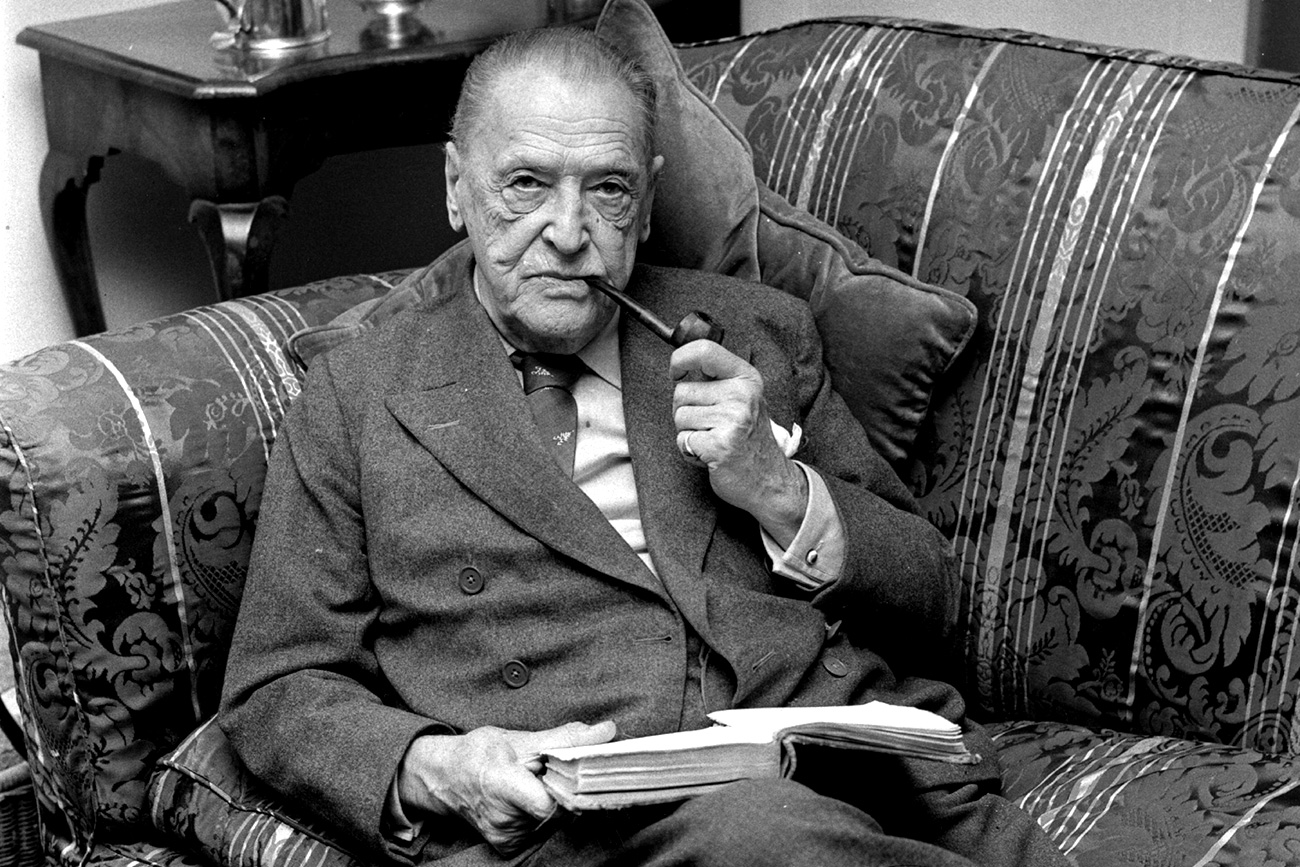

British novelist and playwright Somerset Maugham.

Getty ImagesThe author of Theatre, and The Razor’s Edge was an agent of the British Secret Intelligence Service during World War I, and he was entrusted with a secret mission to Russia, the true nature of which remains a mystery even 100 years later.

The trip to Russia in 1917 was not Maugham’s first experience as a secret agent for British Intelligence. By then he had already worked a couple of years for what later would be known as MI-6. After his first mission in Switzerland in 1915 he wanted to quit for personal reasons – he had divorced and his male lover had been sent out of Britain. However, according to one of his biographers, Maugham was intrigued by the life of a secret agent because he liked pulling strings from behind the scenes.

Nevertheless, when he was approached with the chance to go to Russia, he was uncertain. As he recalled afterwards, he thought that he didn't have the right qualities for the task. In the end, the desire “to see the country of Tolstoi, Dostoievski and Chekov” outweighed any doubts, and he accepted.

Impossible mission

According to what is known about his Russian mission, Maugham was given a very daunting task. As he put it himself, he was supposed “to devise a scheme that would keep Russia in the war and prevent the Bolsheviks, supported by the Central Powers, from seizing power.” By that time the war was unpopular in Russia, and the Bolsheviks demanded immediate peace, which was a main slogan in their propaganda campaign.

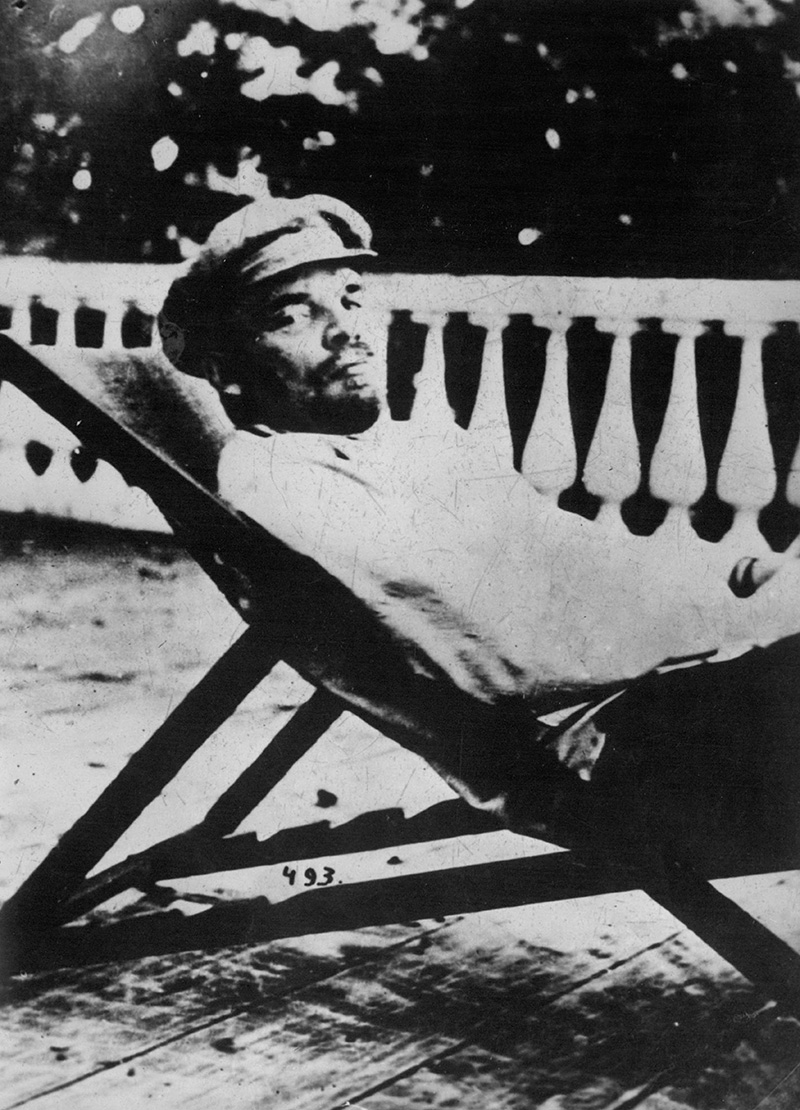

1918. Vladimir Lenin relaxes in Sauna outside on deck in sun. / ZUMA Press/Global Look Press

1918. Vladimir Lenin relaxes in Sauna outside on deck in sun. / ZUMA Press/Global Look Press

Maugham was given financial resources to fulfill the mission, around 21,000 pounds sterling, which today equals about $300 000. There were also several people of Czech origin at his disposal working as liaison officers. There was the hope that Maugham could somehow mobilize and rely upon thousands of Czechoslovakian soldiers who at that time were stranded in Russia. In fact, the following year those units would become one of the main military forces to challenge the new Soviet regime.

Vodka, caviar and disillusionment

Maugham managed to establish contacts with Alexander Kerensky, the Prime Minister of the Russian Provisional Government. Every week Maugham entertained him and his cabinet ministers in one of the finest restaurants in Petrograd, Medved' (The Bear), plying them with much vodka and caviar.

Alexander Kerensky, Russian revolutionary leader. Minister for war in 1917. / Mary Evans/Global Look Press

Alexander Kerensky, Russian revolutionary leader. Minister for war in 1917. / Mary Evans/Global Look Press

Maugham soon became disillusioned with Russia, however. “The endless talk when action was needed, the vacillations, the apathy when apathy could only result in destruction, the high-flown protestations, the insincerity and half-heartedness that I found everywhere sickened me with Russia and the Russians,” he recalled later.

There was one man, however, whom Maugham liked a lot. Boris Savinkov was one of the leaders of a terrorist organization in pre-revolutionary Russia who in 1917 worked for the government. Maugham described his as “one of the most extraordinary men” he ever met. Savinkov had no sympathy towards the Bolsheviks and had no illusion about the resolve of their leader, Vladimir Lenin. Savinkov allegedly said that “either Lenin will stand me up in front of a wall and shoot me, or I shall stand him in front of a wall and shoot him.”

Plan to defeat the Reds

Reading his memoirs, it’s clear that he truly believed in his ability to stop the advance of Bolshevism in Russia, and 20 years later he complained about the lack of time to fulfill the task he was assigned to do.

His confidence, coupled with Maugham’s fascination with the terrorist leader Savinkov, led some authors to think that the agent-writer was planning Lenin’s assassination. Others suspect that he masterminded what later would become the famous Czechoslovak uprising of 1918. Maugham not only established contact with the Czechs, but during his stay in Russia he just happened to visit places where it eventually happened.

General Kornilov and Boris Savinkov, leader of the Socialist Revolutionary Party. / RIA Novosti

General Kornilov and Boris Savinkov, leader of the Socialist Revolutionary Party. / RIA Novosti

Maugham was sent back to London shortly before the Bolshevik revolt in Petrograd in late October. Some insight into his true intentions in Russia could have been revealed by his archives, but the writer destroyed most of it shortly before his death. At the same time, his secret agent experience was used for the collection of stories titled Asheden: Or the British agent, which was published in 1928.

His mission in Russia was his last task for the Secret Service. After returning to the U.K. he devoted himself to writing, but eventually settled on the French Riviera and kept contact with many celebrities of the time, such as Winston Churchill and Herbert Wells.

Maugham died in 1965, at the age of 90, but there is no grave for his body. According to his will, his ashes were scattered around the library named after him at King’s School in Canterbury. It’s believed that Ian Fleming created his character James Bond with Maugham’s Asheden in mind. George Orwell admitted that Maugham was the author who influenced him the most.

Read more: Revolutionary love: Lenin's amorous triangle with his wife and mistress

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox