A Christmas feast of Russian books

A Christmas wish list of the best Russian books.

Alamy / Legion Media

|

| Penguin Classics, February 2015 |

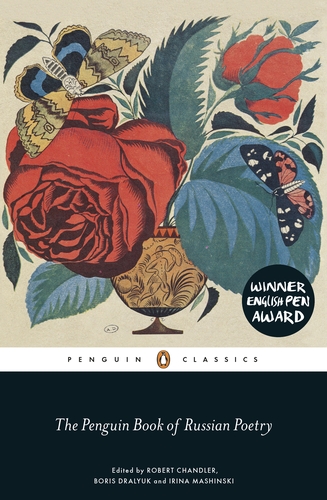

1.The Penguin Book of Russian Poetry

If you only buy one Russian book this year, it should be this one. Robert Chandler and other first-rate translators collaborated for many years in putting together this anthology of poems, and have produced a cultural banquet to delight the Russophile and convert the skeptic. It starts in the 18th century, moving swiftly on to Pushkin and his contemporaries, before sailing bravely through the 20th century and into more recent poetical waters. The morsels in this volume, like Sasha Dugdale’s wonderfully simple translations of Elena Shvarts’s poignant poems about ageing, whet the appetite for more.

|

| Alma Classics, December 2015 |

2. Ivan Goncharov – The Same Old Story

Provincial, romantic, 20-year-old Alexander decides to try his luck as a poet in St. Petersburg. His pragmatic, factory-owning uncle, lighting his cigars with Alexander’s love letters, tries to teach his nephew the ways of the business world. Their sense-versus-sensibility dialogues provide both the novel’s comic core and its philosophical depths. “You created an inner conflict between two competing views of life,” the disillusioned idealist tells his uncle towards the end. Written in 1847, more than a decade before better-known Oblomov, Goncharov’s first novel proves equally engaging in Stephen Pearl’s thoughtful translation.

|

| Alma, April 2015 |

3. Leo Tolstoy – The Kreutzer Sonata and Other Stories

An obsessive stranger encountered on a long train journey tells the narrator of The Kreutzer Sonata a tale of murderous sexual jealousy, censored when it was first published in 1889. Tolstoy transforms his own puritanical, late-life convictions into intense, descriptive prose as his character rails against marriage and advocates celibacy. This varied volume of translations by Roger Cockerell also contains three other stories, including The Prisoner of the Caucasus, which inspired a popular 1990s film.

Read more: The Life and Philosophy of Leo Tolstoy in 15 Photos

|

| Macmillan, February 2015 |

4. Lena Mukhina – The Diary of Lena Mukhina: A Girl’s Life in the Siege of Leningrad

The journal of a 16-year-old schoolgirl sheds painfully human light on a tragic year, beginning in summer 1941, when the city we now know as St. Petersburg was cut off and an estimated 800,000 people died. Amanda Love Darragh has translated Lena Mukhina’s wartime diary, which starts with algebra exams and her secret passion for a boy in her class. When the Germans invade, her city changes, but Mukhina adapts to the sight of silvery barrage balloons and the noise of air raids. By January 1942, in temperatures of -31C, eating jelly made from carpenter’s glue, she writes: “we’re growing weaker every day”. With style and emotion, she records the starving horror of Leningrad’s darkest hours.

|

| Deep Vellum, May 2015 |

5. Mikhail Shishkin - Calligraphy Lesson and Other Stories

Marian Schwartz and others have translated these works, which are “the perfect introduction to Russia’s greatest … contemporary author.” The 1993 short story “Calligraphy Lesson” was Shishkin’s first published work. Like the narrator in Maidenhair, legal scribe and calligraphy teacher Evgeny hears harrowing stories every day and transmutes them into art. The most recent piece in the book, “Nabokov’s Inkblot” written in 2013, is an accessible tale of money, culture and compromise. Along with stories, in Shishkin’s characteristically dense and allusive prose, there are autobiographical fragments, like “The Half-Belt Overcoat”, which revisits his mother’s death and the process of writing The Taking of Izmail, due out in English next year. The volume ends with the breathtakingly brilliant essay on language, “In a Boat Scratched on a Wall”, where the author argues for the redemptive power of literature, “a link between two worlds.”

|

| Gollancz, June 2015 |

6. Victor Pelevin - S.N.U.F.F

Resourcefully translated by Andrew Bromfield, Pelevin is outlandish as ever in his neologism-packed 2011 novel. Damilola, a killer/cameraman from an elite, floating city narrates the story of a futuristic, media-mad dystopia; he spends his life filming the orks of Urkaine [sic] and tweaking the personality settings of his synthetic partner. Damilola’s existential dialogues with his AI companion take them way beyond the Turing test. The novel’s title stands for Special Newsreel/Universal Feature Film, but also suggests the casual murders, which are part of the narrator’s job, and the horrific idea of a “snuff” movie. Pelevin’s savage satires rips open our assumptions about information and interaction; readers who don’t like speculative fiction might feel bogged down by exposition and jargon, but, for fans, this darkly comic classic of the genre explores sex, death and what it means to be human.

Read more: At 50, Victor Pelevin creates myths for the new Russia

|

| Glagoslav, October 2015 |

7. Margarita Khemlin – The Investigator

Margarita Khemlin published this complicated, literary whodunit in 2012 and died in October this year, so Melanie Moore’s robust translation has become a timely memorial. The Investigator, set in struggling, post-war Ukraine, concerns the murder of a girl called Lilia Vorobeichik. The narrator, a former intelligence officer trying to find out who really killed Lilia, is a convincing character, doggedly persistent long after the official investigation has ended; the tensions between his narration and the other voices he gathers are what make Khemlin’s work so unusual. Ultimately, this novel is far more than a whodunit: it’s a crowded, many-layered exploration of families, Jewish heritage, and the horrifying aftereffects of war.

|

| Oneworld, July 2014 |

8. Serhii Plokhy – The Last Empire

Harvard professor Serhii Plokhy, has written a pacey, erudite tome about the end of the Soviet Union, which came out in paperback and won the Pushkin House award earlier this year. More than 400 pages are dedicated to the five months between the July 1991 Moscow summit and Gorbachev’s Christmas resignation. Plokhy uses recently declassified documents and top-level interviews focusing closely on “the drive of the Soviet republics towards independence” and challenging the idea that the US “won” the cold war. Colorful details, like the leaders’ Moscow meal of beef with truffle sauce, bring to life this topical account of a world-changing moment.

QUIZ: How well do you know Russian literature?

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox