Lewis Carroll in Wonderland: the writer's adventures in Russia

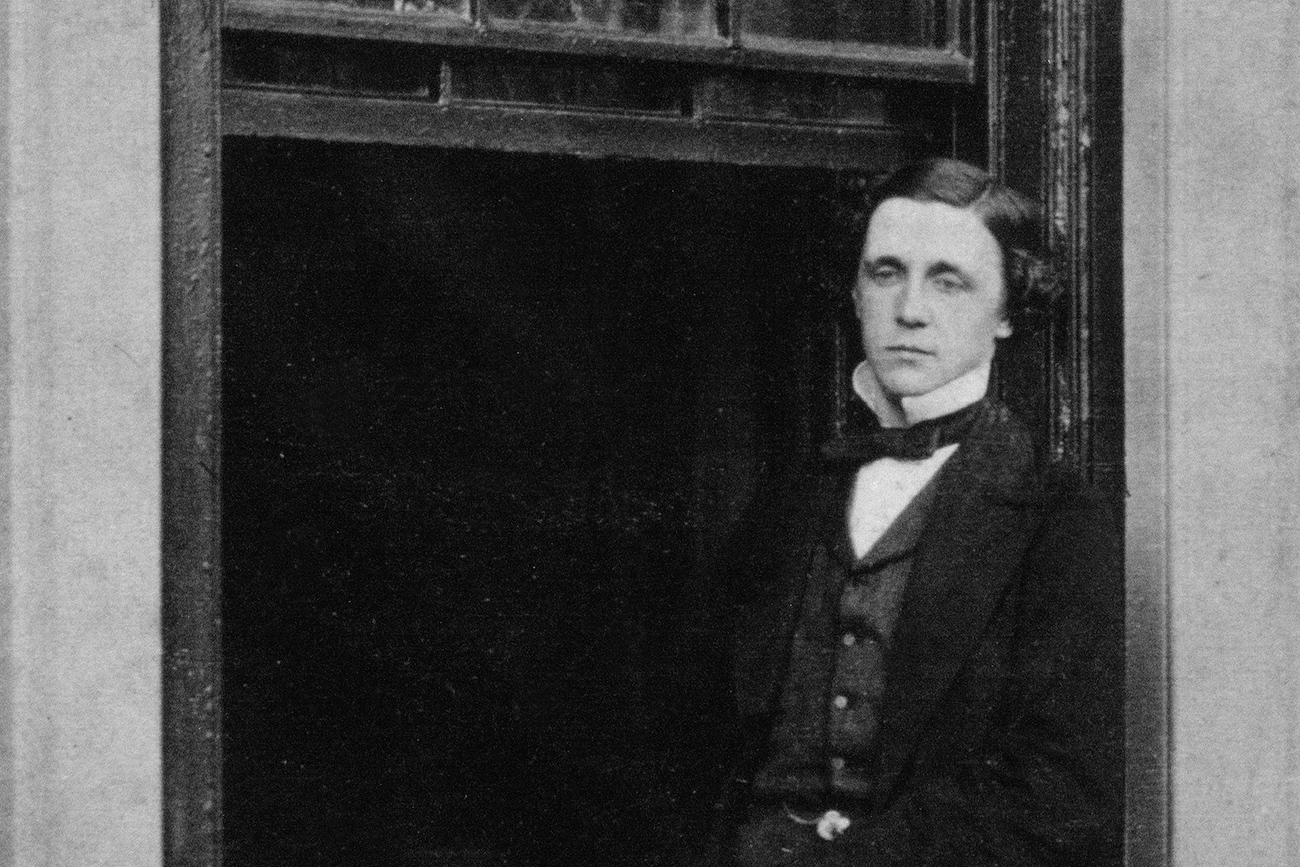

English author, mathematician, and photographer Lewis Carroll, Ca. 1857.

Getty ImagesOne of the major events in Lewis Carroll’s life was a three-city trip to Russia. He fascinated by what he encountered and kept a journal detailing his experiences. This was never supposed to be published, but it was finally released 37 years after the writer’s death.

Lewis through the looking glass

On July 4, 1867, Lewis Carroll’s close friend and colleague Henry Liddon proposed “that we should go together to Russia”, and Carroll gladly agreed. Both men were strong supporters of reunifying the Eastern and the Western Churches, a hot topic of the day, so their trip was officially sanctioned.

They began with St. Petersburg, which captivated Carroll in particular. Even a short stroll after dinner seemed incredible. “It was full of wonder and novelty,” he wrote, “the enormous width of the streets … the huge illuminated signboards over the shops, and the gigantic churches, with their domes painted blue and covered with gold stars – and the bewildering jabber of the natives – all contributed to the wonders…”

They continued on to Moscow where, according to some scholars, Carroll came up with the idea of Through the Looking-Glass. In his diary he wrote that Moscow was a unique city where the scenes of big city life were reflected through a false mirror.

Liddon and Carroll spent two weeks in Moscow, sightseeing and visiting numerous churches and cloisters. During the tour Carroll took pleasure in collecting the trickiest Russian words to pronounce and transcribing them into English. One of his favorites was “Zashtsheeshtschayjushtsheekhsya” – a declined form of a word for people who protect themselves.“The most interesting day” of the journey was August 12, when the pair visited the Troitsky Monastery, where they encountered the most influential figure in the Russian Church: Vasiliy Drosdov Philaret, the Metropolitan of Moscow.

After Moscow Liddon and Carroll made their way to Nizhny Novgorod, where they visited the World’s Fair. Here they were “constantly meeting strange beings, with unwholesome complexions and incredible costumes.”

Carroll’s Russian journey was a landmark event for the writer, and he never left England again.

Russian Alice

Lewis Carroll himself had an undoubted impact on Russian literary culture. Alice in Wonderland (1865) was first published in Russia in 1879 with the title Sonya in a Kingdom of Wonder. Interestingly, neither the translator’s nor illustrator’s name appeared on the title page, and the translator’s identity is still a matter of speculation. There are now more than 30 Russian versions of the book, including ones by Anton Chekhov’s brother Mikhail Chekhov and the prominent children writer and translator Samuil Marshak.

Nabokov’s version, Anya in Wonderland, was first published in 1923 in Berlin and is one of the most popular translations. His idea was to let Russian readers experience as much pleasure in reading the work in translation as in the original. Hence he retold the story in a Russian style, including allusions to great Russian poets in the book’s verse elements.

The literary critic Nina Demurova produced another excellent translation. Unlike Nabokov she did not russify Alice’s story; rather she retained all of Carrol’s neologisms and his general style.

Yefrem Pruzhansky’s cartoon adaptations of the books (1981 & 1982) are classics of Soviet cinema and among some of the most surreal screen versions of Alice’s adventures. Pruzhansky uses blurred backgrounds, dark and mysterious colors, characters all out of proportion and a blue-haired Alice. Interestingly, these psychedelic movies are more popular with adults than children, but most people agree that Carroll himself would have approved of Pruzhansky’s interpretation of his books.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox