Book Review: Andrei Gelasimov's new novel shows all shades of cold

Russian writer Andrei Gelasimov.

facebook / personal archiveInto the Thickening Fog often feels like a quintessential Russian novel: it starts with a bout of heavy drinking, is set in a frozen northern city, and features dogs, demons and existential angst. Andrei Gelasimov’s novels have earned him numerous awards, and this 2015 offering, just out in English, has many hallmarks of his prize-winning playful style.

Classic hangovers

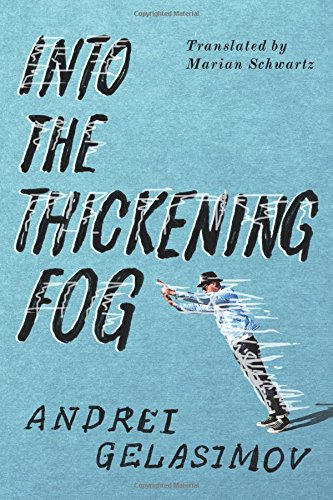

AmazonCrossing, January 2017 AmazonCrossing, January 2017 |

Eduard Filippov, a fashionable Moscow director, finds himself, impossibly hungover, on the floor of an airplane toilet with a misspelled boarding pass in his pocket. He is flying home to the “strange frozen city” where he grew up and where his young wife is buried.

As descriptions of hangovers go, this one is up there with the all-time literary classics, like Kingsley Amis’ Lucky Jim (his mouth had been “used as a latrine by some small creature of the night, and then as its mausoleum”) or Stepan Likhodeev in Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita (“brown spots rimmed with fiery green floated between his eyeballs and his closed eyelids”).

Filippov wakes to find he has “someone else’s head … disgusting, sticky, recalcitrant. The alien head wouldn’t lift.” His other body parts start to revolt; “his stomach demanded to be taken where it could be sick … his hands’ modest wish was to shake and be covered in perspiration.” Filippov’s rallying is comically heroic.

From Shakespeare to Star Wars

Gelasimov’s earlier novels, with their lonely, battle-scarred young heroes, have a similar mix of gloom and comedy. This is the fifth Gelasimov novel that Marian Schwartz has translated, and she is a past master at capturing his allusive, elusive style. Here, his free-range references flap from classical (Circe, Charybdis), biblical (friendship three times denied) and Shakespearean (leaping, like Hamlet, into his dead wife’s grave or quoting Macbeth’s sound and fury) to pop cultural (his noisy breathing like a “raspy, unintelligible, and infinitely lonely Darth Vader”, hair standing up like Doc Brown’s in Back to the Future).

This many-layered cultural tapestry and a strong sense of the town’s frozen atmosphere are the novel’s strengths, outweighing the sporadic tug of its deliberately fractured plot. Into the Thickening Fog has a strong sense of place. Gelasimov himself grew up in the Siberian city of Irkutsk. An indifferent hotel receptionist looks at Filippov and, for a second, “the entire millennial tundra, with its deer, nomad camps, lichen, midges, lost geologists, and hard frosts, was looking at him through her narrow eyes.”

Cold as a character

Cold is both symbol and central character in Gelasimov’s sometimes baffling tale. Schwartz has called the English translation Into the Thickening Fog, underlining Filippov’s confused adventure into the murky past, but the original Russian title means simply “Cold”.

In December 2002, the Siberian city of Yakutsk, where Gelasimov went to University, had a real-life emergency similar to the one in the novel, leaving the city in danger of freezing. Gelasimov uses this extreme cold as an extended metaphor for human alienation, rather than the basis for an apocalyptic scenario (although one character observes “our situation is more of a disaster novel”).

Like all good metaphors, the vivid descriptions of real cold enhance its allegorical force. Ice-crusted power lines are “giant coral threads”, the hoarfrost grows like “tropical vegetation” and crystals of solidified cold stuck in “billions of colonies to any surface in the city.”

The icy tumult is “capable in just a few minutes of dispatching a living creature to eternity.” It is this sense of jeopardy that tries to keep taut the narrative thread through Filippov’s redemptive ramblings. This bizarre, frost-furred, Russian morality play will not appeal to everyone, but its powerful style traces a jack-frost magic that is funny, moving and evocative.

Read more: The best 100 works of world literature, according to Russian writer Bykov

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox