What friends and colleagues say about a leading Russian conceptual artist

Dmitri Aleksandrovich Prigov / German Rovinskiy/Global Look Press

Dmitri Aleksandrovich Prigov / German Rovinskiy/Global Look Press

Dmitri Aleksandrovich Prigov was probably one of the most unusual and eccentric figures on Russia’s culture scene, known for his innovative art works, and innovative “graphic” poems that are even more than poems but geometrical objects. One of his works is even drawn on a Moscow building.

As author of dozens of installations and art performances dating from the end of the 1980s, his artworks today grace galleries all over the world: from Struve Fine Art gallery in Chicago and the St. Louis Gallery of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, to Martin-Groppius-Bau in Berlin. His most recent exhibition was at the Centre Pompidou in Paris in 2016.

Prigov's graphic poem on the building in Moscow's Belyaevo district. / Margarita Chistova

Prigov's graphic poem on the building in Moscow's Belyaevo district. / Margarita Chistova

Other art forms occupied his attention; for example, he penned 35,000 poems, some of which have been translated into English, Italian and German. Avant-garde music was also on his creative horizon, and he was one of the main representatives of Moscow Conceptualism, which is a purely Russian genre with a new vision of art. As many other cutting-edge art movements, Prigov's art was unofficial and non-conformist.

RBTH asked people who knew Prigov about their memories of him as an artist and just a regular guy.

Zelfira Tregulova, General Director of the State Tretyakov Gallery:

The Pompidou Center exhibition of contemporary Russian art, KOLLEKTSIA!, shows not just works by Dmitri Prigov, but also has dedicated a mini-exposition to him inside the display, and where we can understand the scale of the artist’s personality and his importance in the international context. This is without mentioning that many events and lectures were devoted to him in the museum’s program.

The Pompidou Center exhibition of contemporary Russian art, KOLLEKTSIA!, shows not just works by Dmitri Prigov, but also has dedicated a mini-exposition to him inside the display, and where we can understand the scale of the artist’s personality and his importance in the international context. This is without mentioning that many events and lectures were devoted to him in the museum’s program.

I met Prigov personally, and every time our conversations were extremely interesting, paradoxical and at the same time very pleasant. Our meetings were accidental but a sense of warmness remained.

Dmitri Aleksandrovich Prigov. Installation "Crying eye (for poor charwoman)", 1991 / State Tretyakov Gallery

Dmitri Aleksandrovich Prigov. Installation "Crying eye (for poor charwoman)", 1991 / State Tretyakov Gallery

The figure of Prigov still keeps attracting people today. He was a universal man – a poet, a philosopher, an artist – and not in vain was he called a Renaissance man. This universality is why his works are on permanent display both in the Tretyakov Gallery and the Hermitage Museum.

Anton Belov, Director of the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art:

He surmounted time, borders, the physical body and metaphysical influence. Thanks to him we have the chance to estimate art in all variety of aspects. And when we talk about Prigov, we recall not his particular drawings or poems, we recall his image as a whole: how he tried to make opera do performances, cabaret, danced tap and gathered people around himself, traveled to regions and inspired everyone. I think that if to appraise his legacy without discussing which artistic direction he belonged to, then we can say that he had an enormous influence on every aspect of culture. No matter who you are – an artist, curator, manager or just an admirer of art.

He surmounted time, borders, the physical body and metaphysical influence. Thanks to him we have the chance to estimate art in all variety of aspects. And when we talk about Prigov, we recall not his particular drawings or poems, we recall his image as a whole: how he tried to make opera do performances, cabaret, danced tap and gathered people around himself, traveled to regions and inspired everyone. I think that if to appraise his legacy without discussing which artistic direction he belonged to, then we can say that he had an enormous influence on every aspect of culture. No matter who you are – an artist, curator, manager or just an admirer of art.

Eugene Ostashevsky, Russian-American poet and translator:

For me, Prigov and Brodsky were the two major poets of their generation, yet, they are vastly different from each other in their poetry, in their idea of what poetry is, of what language is and what it's for, and what a poet should do.

For me, Prigov and Brodsky were the two major poets of their generation, yet, they are vastly different from each other in their poetry, in their idea of what poetry is, of what language is and what it's for, and what a poet should do.

Prigov is much closer to the Western avant-garde, while Brodsky is more a classicist. Nonetheless, born in the same year of 1940, they form an unexpected pair. It was like a pair of tongs holding between them all of Russian poetry of the second half of the 20th century.

One of my life’s good fortunes was to spend a week with Prigov in Bergamo, Italy in August 1998, at a Russian language summer program where we were doing a reading together for Italian students. A recording of the reading can be found on Penn Sound.

Dmitri Alexandrovich Prigov's exhibition at the Hermitage. / Igor Russak/RIA Novosti

Dmitri Alexandrovich Prigov's exhibition at the Hermitage. / Igor Russak/RIA Novosti

He read Almaznaia azbuka, (Diamond Alphabet), a giant verbal-musical-conceptual piece that oscillated between the Soviet version of Pop Art and the Soviet reception of Buddhism. You could not tell where the irony ended (if it ended), and it was just astounding. It flabbergasted me. And then he read his post-Soviet “Stratifications,” pieces on conversion, as in currency conversion—this was still the period when no one knew how to address the post-Soviet era in literature.

I was walking through the Centre Pompidou recently, and I saw and heard him. There was a mini-exhibit in his memory, and his voice was piped into different locations on the fourth floor. It is very hard to believe that ten years have passed since his death.

Valentina Polukhina, Professor of Keele University:

I had the opportunity of meeting Dmitri Prigov quite often, because he visited my university [Keele University, Staffordshire] several times. In 1995 we published a bilingual collection of his poems, Texts of Our Life. His witty poems and unique manner of reading captivated our students and teachers so much that my colleague Robert Reid and my PhD student Chris Jones translated his poems into English almost as well as professional translators. I wrote an introduction or this collection.

I had the opportunity of meeting Dmitri Prigov quite often, because he visited my university [Keele University, Staffordshire] several times. In 1995 we published a bilingual collection of his poems, Texts of Our Life. His witty poems and unique manner of reading captivated our students and teachers so much that my colleague Robert Reid and my PhD student Chris Jones translated his poems into English almost as well as professional translators. I wrote an introduction or this collection.

The popularity of Prigov's book exceeded all our expectations. Teachers and students from other departments attended his evenings. He liked our campus, its pond and parks so much that he often came there to work in peace. He was an easy guest, always in a good mood, he didn’t drink or smoke, and never spoke badly about other people or poets. When I moved to London, he visited me and my husband, and was even my official witness at our wedding, when a friend fell ill so that we needed another witness at the last minute. I called Prigov and asked if he’d agree to take on this role. He answered my question with a question “What is concealed behind this request?” he asked me. “Nothing,” I replied, adding mischievously , “Except that f my husband throws me out of the house, then I will move in with you.” – “Ok, then I agree,” – was his answer.

Olga Matich, Professor of Russian literature at the University of California, Berkeley:

Dmitri Aleksandrovich was persecuted by the KGB, and at the beginning of perestroika he was sent to a psychiatric hospital because he was hanging posters in Moscow with quotes by Nekrasov, for example "Remember, You do not have to be a poet, but you must be a citizen." Under public pressure, however, they released him. Times had changed. My favorite memory of him is a virtuoso performance of Mantras of Russian High Culture at Berkeley. He performed Evgeny Onegin's first paragraph in a Buddhist manner. <...>

Dmitri Aleksandrovich was persecuted by the KGB, and at the beginning of perestroika he was sent to a psychiatric hospital because he was hanging posters in Moscow with quotes by Nekrasov, for example "Remember, You do not have to be a poet, but you must be a citizen." Under public pressure, however, they released him. Times had changed. My favorite memory of him is a virtuoso performance of Mantras of Russian High Culture at Berkeley. He performed Evgeny Onegin's first paragraph in a Buddhist manner. <...>

Watch Evgeny Onegin in a Buddhist manner from 11:31 minute in the video. Source: YouTube / Russian Writers at Berkeley

Once Prigov was our guest, and in the mornings he would bring us a bunch of poems written during the night. When I asked him to show one of them to me, he said that individually they have no special significance, that he was working on a project - writing a specific number of poems. I don't remember how many, but it was a huge number that recalled the Soviet Stakhanovites. In other words, he was using graphomania as a device. <...>

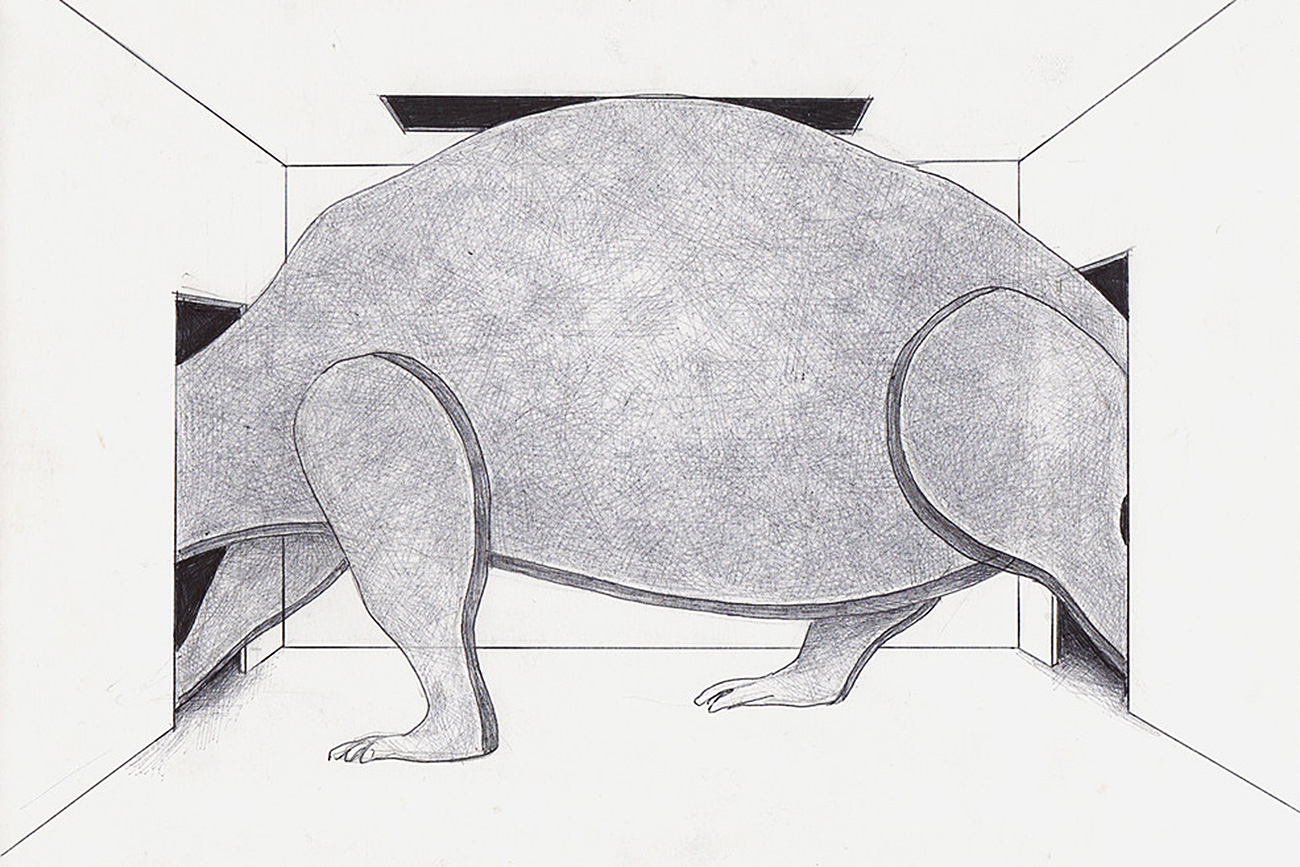

Dmitri Aleksandrovich Prigov. From the "Phantom" installation. / State Tretyakov Gallery

Dmitri Aleksandrovich Prigov. From the "Phantom" installation. / State Tretyakov Gallery

Prigov performed at Berkeley in 2001, not long before Kabakov. It can be said that our spring semester passed under the sign of Moscow conceptualism. <...> That time he also stayed at my place, working nights on graphic images using multi-colored inks and also brought that which he created in the mornings. We talked a lot about life, especially I remember his recollections of how as a child he spent about six months in bed because of polio, and how diligently he fought its aftereffects, doing exercises to restore his muscles.

"I managed to overcome the aftermath of the paralysis, but as you see, I still limp," he said.

He applied this systematic approach, perseverance and constant work to his art.

(Material taken from Olga Matich's book, Memoir of a Russian-American with permission of the author)

Nicolas Liucci-Goutnikov, curator of the Kollektsia+exhibition at Centre Pompidou :

Dmitri Prigov is definitely one of the most important figures of Russian contemporary art. Although deeply rooted in langage, e.g. Russian literature, his work has imposed an international visual idiom dealing with both metaphysics and politics, transcending any kind of borders and assignments thanks to his all-encompassing energy. Thanks to Nadia Bourova, Centre Pompidou is very proud to now hold in its collection a significant ensemble of works by Prigov, which allow the museum to renew its perspectives on conceptualism.

Dmitri Prigov is definitely one of the most important figures of Russian contemporary art. Although deeply rooted in langage, e.g. Russian literature, his work has imposed an international visual idiom dealing with both metaphysics and politics, transcending any kind of borders and assignments thanks to his all-encompassing energy. Thanks to Nadia Bourova, Centre Pompidou is very proud to now hold in its collection a significant ensemble of works by Prigov, which allow the museum to renew its perspectives on conceptualism.

Alessandro Niero, Italian translator of Prigov's poetry:

I met Prigov in 1997 when he was my guest for several days, but I don't remember exactly when it was. In any case, it was a soulful conversation full of inspiration and wit. A talk with him was a constant rethinking of the idea of poetry.

I met Prigov in 1997 when he was my guest for several days, but I don't remember exactly when it was. In any case, it was a soulful conversation full of inspiration and wit. A talk with him was a constant rethinking of the idea of poetry.

His disappointment matched an extraordinary passion to such a phenomenon as language. I was very inspired by those moments when he read his poems, and he communicated on the edge of linguistic communication, and because of that, those who didn't even know Russian were charmed.

His works were a significant attack on the lyrics of Russian poetry. I hope I'm not exaggerating, but he tried to change the very idea of poetry, investigate its possibilities as an instrument in the expression of feelings; as well as being an instrument in asking political, social and philosophical questions.

There is a healthy pars destruens in the concept of his art, and one who starts writing (wherever he is) should ask himself not banal questions about poetry but try to find his own personal deliberate and not naive pars costruensem>. For me, Prigov's works are an unlimited meta-literary action that doesn't include previous aesthetically pleasant and beautiful lyrics.

Read more: Where to find contemporary art in Moscow and St. Petersburg

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox