Depicting Americans through the lens of Russian cinema

Russian actor Viktor Sukhorukov (in center) in Chicago policemen's clutches during the shooting of a new film "Brother-2" which will tell about the further life of Danila Bagrov.This time Danila Bagrov will fight Russian mafia in the U.S.

TASSFor a long time, the Soviet Union and the U.S. tried to understand each other, including through the prism of cinema. Obviously, in conditions of ideological confrontation the film characters were caricatures, which is why it's interesting to study these clichés.

The image of the American in Russian cinema has transformed from a caricature cowboy, a visiting circus performer in the 1920s and a then Cold War spy, into ordinary exchange students today who do not understand Russian life but love it the way it is.

We are better than you

In early Soviet films, the American protagonist was a good person who when visiting the Soviet Union discovers his best qualities, unlike people from the USSR who in America remain captives to their illusions.

Filmmakers in the early Soviet Union had an inferiority complex in relation to Hollywood. They borrowed American techniques and genres, from the Western to the Musical, adapting them to Soviet reality.

Visitors from America were usually caricature businessmen, similar to the Rothschilds and Rockefellers, cowboys and performers stylized after Marlene Dietrich, such as the heroines played by Lyubov Orlova. The Americans, who were frightened back home of Communist life, came to the USSR and marveled at Soviet citizens' kindness and social equality.

One of the most famous 1920s Soviet films, The Extraordinary Adventures of Mr. West in the Land of the Bolsheviks, was made by Lev Kuleshov (1924), and it shows the stereotypes of that era. The protagonist is naïve and credulous, and soon becomes a victim of extortion scams, but everything ends well after a policeman shows him the new Moscow that the Bolsheviks created. In the role of the former aristocrat turned thief, Kuleshov casted an actor from an old noble family, Leonid Obolensky.

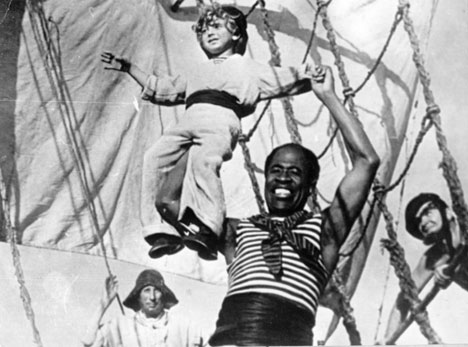

Twelve years later in the Circus (1936), American performer Marion Dickson, played by Lyubov Orlova, joins the Soviet circus. She hides a terrible secret - that the father of her son is a black man - and she is basically a slave of her American agent and patron.

In the USSR, however, where supposedly there is no racism and all nationalities and races live in friendship under Stalin's thoughtful leadership, the secret is no longer shameful. Together with a reliable Soviet comrade, the American woman, having become a Soviet citizen, can now march in a parade under the banner of a radiant future.

Circus. / Photo: Kinopoisk.ru

Circus. / Photo: Kinopoisk.ru

Enemy among us

After WWII, the Soviet attitude towards Americans drastically changed, and so did the portrayal of American visitors. Usually, it was a journalist who was fighting on one side of the barricades or another. In The Russian Question (1947) directed by Mikhail Romm, journalist Harry Smith (Vsevolod Aksenov) is sent to the USSR to write a propaganda report about the horrors in the country, but he returns with inspirational material that displeases his superiors. He loses his job and becomes an outcast.

In Encounter at the Elbe, which was the 1949 Soviet box office hit with 24.2 million people seeing it, Lyubov Orlova plays journalist Janet Sherwood, who is actually a CIA agent preparing a conspiracy with the help of the Nazis. This was the most brazen ideological state-ordered film that Grigory Alexandrov ever directed, and it's no wonder that the following year he received the Stalin Prize, together with Orlova.

Renowned director Alexander Dovzhenko's Farewell, America had an interesting fate. Based on a book by former U.S. State Department employee Annabelle Bucar, who took Soviet citizenship and worked all her life on Moscow radio, the film's protagonist, American journalist Anna Bedward (Lilia Gritsenko), is stationed at the American Embassy in Moscow where she becomes disillusioned with the working methods of her government and defects to the USSR.

Farewell, America. / Photo: Kinopoisk.ru

Farewell, America. / Photo: Kinopoisk.ru

Dovzhenko shot the film as direct agitprop. "Read your lines in a way so that I can hear the gross rhythm of capital," is what he told the actors, while employees of the American embassy were alcoholics, debauchees and hysterics. Stalin personally ordered the film shooting to stop, believing that Bucar was unreliable. The unfinished film was restored and shown at the Berlin Film Festival only in the middle of the 1990s.

Classics of mature socialism

In 1970, Soviet cinema liberated itself from its inferiority complexes in relation to Hollywood, although many genres such as the Western and the Musical had been borrowed from America. Screen adaptations of books by American authors came out regularly and showed classical inequality and capitalistic greed as the main defects of the Western system.

The Headless Horseman. / Photo: Kinopoisk.ru

The Headless Horseman. / Photo: Kinopoisk.ru

Soviet directors freely shot films based on novels by: Robert Penn Warren (All the King's Men, about corrupt American politics, 1971); Mayne Reid (The Headless Horseman, 1973); Lionel White (Rafferty - about union corruption and links to the mafia, 1980); Irving Wallace (The R Document - about a coup d'etat in America, 1985); and many others. The battlefield was no longer in the Soviet Union, but on the territory of the ideological enemy itself, and social criticism was added in those cases when it did not exist in the original sources.

No longer enemies

From the end of the 1980s, when immigration to America began, the subject of choice and cultural differences in the two countries was very popular in cinema.

InAmerican Daughter (1995) Vladimir Mashkov's protagonist lands in an American jail for having kidnapped his daughter, who his former wife brought to America. Shirli-Myrli ( 1995) is a story about two identical twins who, after reuniting, admit they "hate black people," only to find out that they have a black-skinned brother in the U.S. who their mother gave to the American Embassy shortly after birth.

American Daughter. / Photo: Kinopoisk.ru

American Daughter. / Photo: Kinopoisk.ru

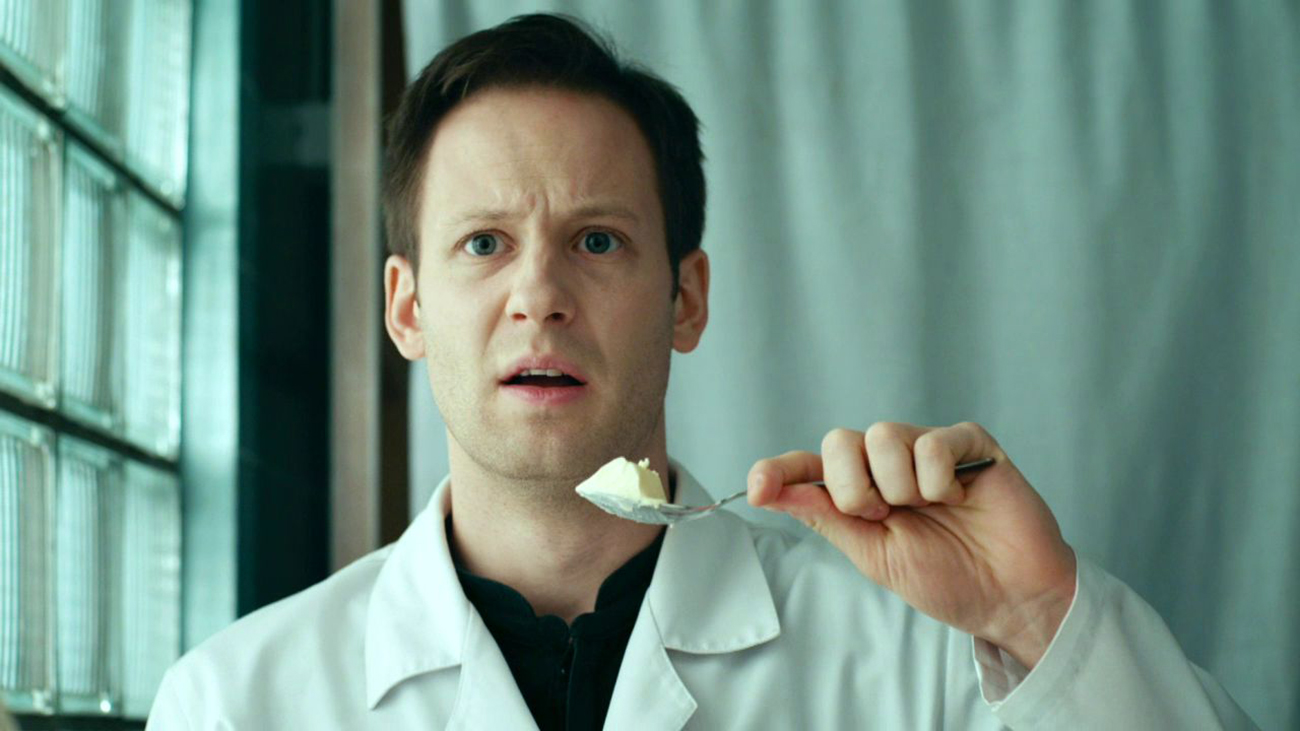

The subject of the American in Russia has drastically changed. Today, the American in Russia is usually an exchange student, such as Phil Richards in the sitcom Interns (2010). Everyone laughs because he cannot understand why everything is so illogical in Russia.

Interns. / Photo: Kinopoisk.ru

Interns. / Photo: Kinopoisk.ru

Now, relations between the two countries have matured so that cultural particularities and differences are dissected the way they would be in any Hollywood comedy. For example, the visiting American never understands why Russians eat aspic, or herring 'under the fur.'

Whatever the political relations between the two countries might be, it's unlikely that Russian cinema will again portray Americans as a threatening and dangerous force. When in the 1980s Ronald Reagan called the USSR, "the Empire of Evil," George Lucas was horrified. For the director of Star Wars any government is an empire of evil.

Read more: What do Hollywood stars have to say about Russia?

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox