Soviet avant-garde filmmaker to world classic: Dziga Vertov

Dziga Vertov at the shooting of a film. A still from the documentary "The Gameless World".

RIA NovostiDziga Vertov was the first to consider film not as a theatrical performance or a historical document, but as an independent artefact.

"I am the cinema eye. I am a mechanical eye. I am a machine showing you the world in the way only I can see it," he said in his early manifestos.

For Vertov, the impact of a film on the viewer was related not to the actors playing out an entertaining story in front of the camera, nor to the camera being placed in a specific location, for example a meeting where Lenin was supposed to speak. Its primary impact was from the changing of full shots, medium shots and close-ups, by the rhythm with which the shots alternate, and how fast and slow motion were used.

Even official events, which he shot (between 1922 and 1925, Vertov managed the department of film chronicles at the All-Union Film Association, then State Cinema, which produced films in the USSR, and worked as a censor), were filmed from unexpected points and angles: from a moving car, a factory pipe, or the wheels of a train, with a hidden camera.

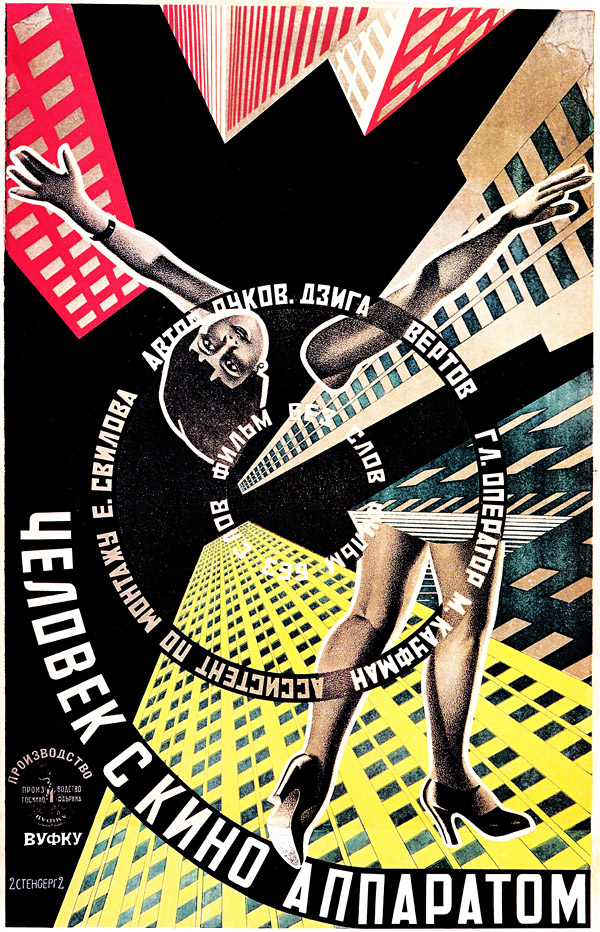

The plots of Vertov's earlier films have secondary meaning. His most famous and radical films, Cinema Eye (1924) and Man with a Movie Camera (1929), are large-scale film frescoes whose plots can be summed up with short phrases: "Life in a big city" and "The old and the new," while their artistry is generated by the parallelism of shots and the impetuous rhythm of the editing. The first film won a medal and a diploma from the World Exhibition in Paris (1924) while the second was elected one of the ten best films of all time and the best documentary film, by European film critics in the 2010s.

Source: YouTube

Editing from the past

Of course, the cinematographic language in the 1910-20s was developing in various countries, in both narrative and documentary films, and later in sound films. But Vertov indeed anticipated many of the works made by David Griffith, Fritz Lang and Leni Riefenstahl, whose Olympia (1938) is considered a model for documentary film.

However, like any avant-garde artist who is not aware of it, Vertov was very close to long-established traditions. The articles of the great Russian writer Lev Tolstoy contain a categorical refusal of the conventions of traditional theater (Shakespeare's plays and classical opera), but also the idea that anticipated the concept of film editing: that art is born not with the description of vivid characters and their vicissitudes, but only with their "connection," that is, editing.

A restless name

Vertov's real name was David Kaufman, which unambiguously points to his Jewish origin. But the desire of the talented youth from Belostok (at the time part of the Russian Empire, today Poland) to change his surname upon arrival in Moscow could hardly be due to anti-Semitism - in the 1920s it was not as developed as in the 1950s. Vertov, like many avant-garde artists, just chose a new name to herald "the new life."

In Ukrainian "dziga" means whirligig, spinning top, while "vertov" comes from the verb "vertet" (to spin). The two form something like "the spinning whirligig," which fully corresponds to the name's carrier.

Furthermore, Kaufman is a common Jewish surname and would doubtfully have become a "trademark." Dziga's brother Boris Kaufman, being tens years younger, emigrated from Russia after the revolution, graduated from Sorbonne in Paris, moved to America and became a famous director of photography, working with Sydney Lumet and Elia Kazan. In fact, Kazan's On the Waterfront brought Boris an Oscar in 1953.

Resurrected in Dogma

Fortunately, Vertov was spared the tragic fate of many avant-garde artists. He was not shot and was not sent to the camps. But after the Soviet government's brief affair with the avant-garde, Joseph Stalin began to favor "the imperial style" and Vertov's innovative work was no longer useful.

The Man With the Movie Camera, or Living Russia. an experimental 1929 silent documentary film, with no story and no actors, by Russian director Dziga Vertov, edited by his wife Elizaveta Svilova. Source: DPA/Vostock-Photo

The Man With the Movie Camera, or Living Russia. an experimental 1929 silent documentary film, with no story and no actors, by Russian director Dziga Vertov, edited by his wife Elizaveta Svilova. Source: DPA/Vostock-Photo

During WWII Vertov shot three promotional films but all his other proposals were refused. From 1944 to his death in 1954 he worked as editor at the cinema magazine Dailynews.

Interest in Vertov was resuscitated towards the end of the 20th century when directors who signed the Dogma-95 (a conceptual manifesto of independent cinema in the 1990s whose ideologist was Lars von Trier) basically returned to the principles that Vertov had once declared: shooting in natural conditions, hand-held photography, hidden camera and real characters. In 1995 Michael Nyman created his original soundtrack to Man with a Movie Camera. That is how avant-garde director Vertov became a classic.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox