Another perspective on the adoption debate

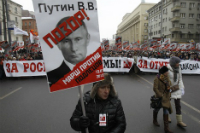

Protests against a ban on Americans adopting Russian children. Source: Maxim Blinov/RIA Novosti

There have been some heated debates over the decision to ban adoption of Russian children by Americans. The Russian blogosphere and social media picked off from where the protestors in Moscow left off last Sunday. I personally think a mountain is being made out of a molehill when you consider the fact that there were less than a thousand children adopted by Americans last year. I am not even going to hint that Sunday’s protestors were “paid Muscovites,” but I can’t help but see crocodile tears in the eyes of some of these activists.

Children around the world have the right to a better life and let there be no debate on that but is America really the land of milk and honey? As someone who was raised in the United States at a time when the country was in better shape than it is now, I can safely say that the country wasn’t even close to being the kind of “paradise” that its mainstream filmmakers and spin doctors would have like the world to believe.

The idea that once a child gets adopted by an average American family, he or she will have a privileged upbringing is absolute nonsense. According to the website of SOS Children’s Villages (an NGO known for its good work with orphans), “25,000 children age out of the (American) foster care system every year at age 18.” So, if well-meaning Americans really want to adopt, they don’t have to look as far as Russia.

The concerned Muscovites, on the other hand, would be well served to work on changing attitudes towards adoption within Russia. RIA Novosti reported this week that 128,000 orphans in the country were in need of adoption. One major hindrance towards these children being accepted by families in the country is the way many members of society look at them.

I cite a personal example of a childless couple I was close to in the Russian Far East a few years ago. They once asked me about how easy it was to get to the town of Puttaparthi in southern India. The couple wanted to meet the now-deceased ‘god man’ Sathya Sai Baba. They felt his blessings would help them with their problem. I suggested a much quicker and cheaper option: a local orphanage, where I occasionally volunteered. The bigger children adored the “chocolate uncle,” who earned his name both for the colour of his skin and the fact that he was generous in gifting candy.

The couple quickly dismissed the idea and fired back with a set of reasons, which shocked me the first time I heard them. “The child may be cute, but he could be the son of a criminal and you never know if he grows up to become one!” I unsuccessfully tried to convince them that no human being is born a criminal and that it was highly unlikely for a child raised in a loving family to turn to a life of crime. I heard other excuses like the impossibility of knowing the family history of diseases! As I was to discover, this couple was not an exception but reflected societal thinking in a large way. I heard similar arguments from several other people from all strata of society.

The Russian government is looking at improving conditions in orphanages in the country, which house about 105,000 children. But this is no long-term solution. Assimilating orphaned children into loving and caring families is the only way to ensure they have a better upbringing. This won’t be possible until ridiculous beliefs about genetics and the likes are rubbished by a significantly large number of people.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox