Lessons from Kashmir LOC

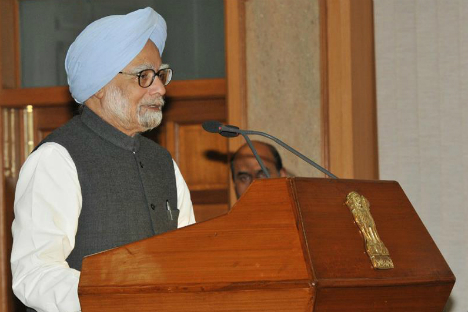

Prime Minister Manmohan Singh underlined that India needs to thinks of ways of taking the relationship with Pakistan forward by addressing the constituency which believes in democracy. Source: Photo Division, Government of India

Was it a military confrontation – the weeklong India-Pakistan acrimony over bloody incidents on the Line of Control? Or, was it a flashpoint? In retrospect, it was more like a brawl – a noisy, disorderly quarrel.

Indeed, it ended as abruptly as it erupted and very little broken china is visible as the protagonists who apparently went for each other’s jugular veins summarily pulled back. To be sure, a cleaning up operation is necessary but, fortunately, no permanent fixtures have been damaged on the dance floor – although the waltz cannot resume as if nothing happened.

Meanwhile, what lessons can be drawn? At least a dozen can be discerned.

First and foremost, the fracas drew attention to a barely-visible aspect of the tenuous security situation on the LOC, which, unlike the India-Pakistan Boundary is an ill-defined line drawn up hastily out of the defunct Ceasefire Line even as the 1971 war ended, with very many salients in the difficult terrain not easy to defend for both armies and where, therefore, a constant, tenacious dog fight has been going on to “straighten” the LOC for gaining unilateral advantage.

Geopolitics in Asia: Russia, India and Pakistan-China Cooperation

The point is, it is futile to apportion blame or impractical to isolate and dissect any particular incident howsoever gruesome it might be as precisely where discord erupted. Have such brutal incidents taken place in the past? The answer is ‘yes’, and both sides have committed abdominal acts.

A long-term solution lies in the LOC attaining the sanctity of an international border but then, it is directly linked to the resolution of the Kashmir dispute.

From the Pakistani viewpoint, keeping Jammu & Kashmir in a state of controlled animation is a politico-military necessity. This is for various recognisable reasons some of which are linked to Pakistan’s internal politics and the geopolitics of the region, while others would relate to the flawed relationship with India.

Following from this, it is important for the Indian side to remember that the famous November 2003 ceasefire announced by the then Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf (and which has largely held up until recently) was a unilateral decision by the military dictator and not the outcome of a negotiated bilateral arrangement between the two countries.

If a decade ago, it suited Pakistan to unilaterally opt for a ceasefire on the LOC and redeploy its troops to the western front due to the emergent situation of the war in Afghanistan (and the growing tensions on the Afghan-Pakistan border), there is a qualitative difference in the situation today.

Unsurprisingly, there is a gnawing anxiety in the Indian mind whether today’s situation is going to be any less dangerous than that in the late 1980s when Pakistan “defeated” a superpower and sent it packing home from the Hindu Kush and thereafter reset its sights on India and redeployed the militant forces of ‘jihadism’ who had by then become redundant but were raring to go in search of new pastures.

Lest it be forgotten, already by the end-1980s and early 1990s, J&K was bleeding profusely and a “low-intensity war” was in full swing, with Pakistan in full battle cry.

Suffice to say, therefore, it will be exceedingly foolish on India’s part to lower guard that the last week’s heightened tensions have subsided and the guns have fallen silent on the LOC. The plain truth is that there is no certainty whatsoever that the lull during this week is going to be enduring.

The best spin that can be given is that the Pakistani army, which is credited to be a professional army, couldn’t have stooped to the extent of mutilating and disfiguring dead bodies of Indian soldiers and therefore it must be the handiwork of some “non-state actors”.

But there are no serious takers on the Indian side for this thesis, considering that the LOC is highly fortified and the Pakistani army is indeed a capable army that is not hoodwinked by “jihadi” elements.

Nonetheless, New Delhi would have taken note that the Pakistani GHQ in Rawalpindi did not react to the statement by the Indian army chief General Bikram Singh warning of “aggressive” response to future ceasefire violations.

In fact, Pakistani assurances followed within 48 hours at the level of the Director-General of Military Operations that strict instructions have been issued to local units to observe ceasefire on the LOC. Interestingly, Pakistani army chief Gen. Ashfaq Kayani never once spoke through the entire week. The signal seems to have been that nothing extraordinary had happened on the LOC.

Of course, uninformed Indian opinion might conclude that Pakistan “blinked”. But there is much more to what happened than meets the eye. The confidential exchanges at the top echelons of the Indian and Pakistani military leadership have always been meaningful, and both sides try to comprehend each other’s compulsions (even whilst disagreeing).

Suffice to say, the recent fracas brought to end by the military leaders, at which point politicians and diplomats are taking over. However, it goes to the credit of politicians and diplomats that they also created a legacy in the current history of the India-Pakistan relationship.

Neither side tried to “internationalise” the recent tensions. The two major influences on Pakistan – China and the United States – actually advised the efficacy of the bilateral track.

The dialogue track remains open, too. India’s diplomatic voice consistently sounded conciliatory even while the political voice addressing the domestic audience spoke stridently. In sum, the dialogue process may have slowly, steadily begun kicking in despite serious shortfalls in substantive outcome so far.

Again, it wouldn’t have escaped notice in New Delhi that there has been a near-complete absence of rhetoric or “war mongering” on the part of the Pakistani politicians and political parties. This is further confirmation that the political discourse within Pakistan has significantly transformed.

Prime Minister Manmohan Singh rightly placed this transformation in the within the matrix of that country’s democratisation process, and, more important, he underlined that India needs to thinks of ways of taking the relationship with Pakistan forward by addressing the constituency which believes in democracy. The outcome of the political struggle in Pakistan will have great bearing for the India-Pakistan dialogue.

The recent fracas will serve a purpose if it gives a new sense of urgency and injects new life into the dialogue process. But that is too much to expect new thinking at this juncture.

India’s capacity to influence the processes in Pakistan remains limited and if anything, the political priorities for the Indian leadership as the general election in 2014 draws closer virtually preclude the scope for major foreign-policy initiatives. For Pakistan too, an assertion of civilian supremacy in policymaking on issues of core concern to India such as the infrastructure of terrorism existing on its soil is a long haul. Least of all, the geopolitics of the region remaining as complicated as they are at present, the easy route will be to hunker down until things gained greater clarity.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox