Space objects remain elusive, but we escape arrest

Artem Zagorodnov: "Local cops were happy for the help." Source: Artem Zagorodnov

Space objects remain elusive, but we escape arrest

I switched cars and am now traveling with Inna, Peter and Vadim (also of the Lemax team). Inna is responsible for the company's human resources department (it has over 700 employees), Vadim runs it's R&D and Peter is responsible for all energy processes at their facilities.

We decided to get a head start on the day and skip breakfast. Alas, to no avail – after driving for five minutes we encountered another closed road. An armed policeman told us to turn around. There was, however, a glimmer of hope in all this. Let me explain.

Inna and Peter during a rest stop. Source: Artem Zagorodnov

By turning around we abandoned hope of making it to Kazakhstan's new capital, Astana - a modern oasis full of monuments to the nation's repeatedly re-elected president - but our tracking system told us that the blizzard had knocked one of the space capsules half way across the country. So heading north toward Omsk, Russia, we would both be on our way to the next part of the journey and have a faint hope of accomplishing the mission, after all.

Which is a good time to reflect on our failed secret plans – at the last major pit stop way back in Novgorod, Lemax's team captain had managed to secure an informal alliance with one of the other teams, Our Alaska (named after an upcoming expedition to America's 49th state).

The two captains had decided that it was nearly impossible to make it to the Baikonur Cosmodrome and back to Siberia in the time allotted, and that presumably the much-coveted space objects wouldn't land by the side of a highway. The organizers had promised to launch five capsules in total – beginning in Baikonur and finishing closer to Astana.

For extra help, Our Alaska had contacted somebody in Kazakhstan's Ministry of Emergency situations who had promised us helicopter support (for a fee).

Once the capsule landed, we would send them the coordinates and their pilot would pick it up, drop it off with another contact in Astana (if we weren't there by then), who would deliver it to us. We had to get a minimum of two capsules with this strategy (for the two teams splitting the bill), but why not three or four we reasoned? That would make for a triumphant entry into Ruyan-City, our next destination in Siberia, and maybe win the entire competition.

Easy, right? We had our sights set on victory until the competition's organizers filed their next press release, which went something like “we won't tolerate teams sitting somewhere in Omsk drinking tea while outsiders pick up their capsules...this will lead to disqualification.”

At first we were angry. The organizers had always clearly stated that outside help was allowed as was anything not specifically forbidden in the rules. But our anger gave way to resignation – we soon learned the Cosmos (“space”) team had driven all the way to Baikonur and had picked up the first capsule. They were to be rewarded for their diligence and mad driving through the steppe.

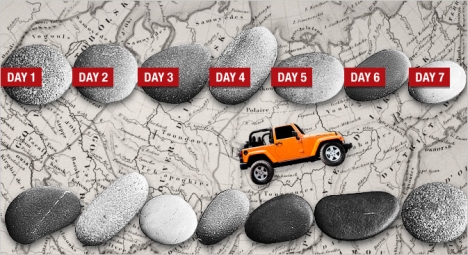

The map of the 2013 Expedition Trophy route. Click to enlarge |

After this mayhem, we still hung on to the hope that we could pick up one of the capsules on the way back to Russia. But it was not meant to be – thirty minutes later, we discovered the road to Russia—closed. The Kazakhs had found a brilliant method of fighting snowstorms, car accidents and poor roads – close the highways!

This time the drivers were angry. Some told the three officers guarding the post that they would simply drive through. In turn, the police promised to arrest them.

A senior officer arrived; one of my team members explained our plight. It's a major international competition, he said; we have journalists – what are they going to write? The senior officer threatened to punish me for taking pictures of the unfolding events. “This is a public place; I can take pictures if I want,” I pleaded. “Not in the Republic of Kazakhstan,” I was told.

Just as I was contemplating blogging from a Kazakh prison cell, word came from a nearby side street that fellow officers had gotten stuck in the snow. We dispatched our jeeps to help, and soon were pulling their vehicle out of the snow. These officers didn't mind being photographed – one even shot me a smile.

Road cleaning outside Novosibirsk. Source: Artem Zagorodnov

As we came back to the closed road, the officers looked the other way as our two jeeps quietly drove past their ad hoc checkpoint. Around midnight we crossed back into Russia and headed to Ruyan-city.

Upon sober reflection, I could see why the police closed these roads off. The weather has not improved and most of the time we are driving through a blizzard.

Under normal circumstances one would be insane to go out in this weather, let alone race. The wind is howling constantly, the sides of the roads are littered with cars and trucks (we pulled out three today; some accidents looked serious) and our windows and doors are frozen over. I constantly have to knock the door open with my shoulder to break through the ice.

Visibility is sometimes so bad we are literally driving into a blanket of pure white and fog lights are of no help.

I also learned that the first team I traveled with, Trust, had been in an accident. They were not hurt, rather miraculously, but one of the cars was totaled after colliding with an oncoming truck. It served as another reminder of the constant dangers we are all facing in the name of team building.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox