Recalling the Soviet past: Line, deficit, string bag

Click to enlarge the image. Drawing by Niyaz Karim

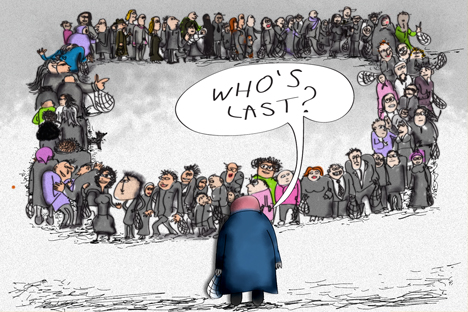

Store shelves were occupied by “unsellable” items, that is, goods for which there was no demand. If something that was truly needed went on sale, a line formed for it, sometimes for hours on end. This situation was described with the verbs “to give” or “to throw out” (the short from of the expression “they threw it out for sale”), as in: “They’re giving coffee at the bakery!” or “They threw out jeans at the department store!”

There was a popular joke about a woman who, seeing a line, walks up to the end of it and asks, “Who’s last?” and then, “And what are they giving?” The joke is not very far from the truth: Soviets, even when they did not set out to go shopping, would carry with them a mesh bag just in case. As early as the 1930s, thanks to stand-up comedian Arkady Raikin, this bag got the name avoska, or “string bag.” The name comes from the old Russian word avos, which can be translated as “What if?” The bag was carried just on the off chance you might run into a line where something was being given out.

The very existence of a line meant that something truly needed was being “given,” and if it was being “given,” it needed to be taken.

Remaining in line was not a requirement: you could simply “occupy a place.” Someone would ask, “Who’s last?” and after receiving an answer, would say to the last person, “I’m after you.” It was considered completely acceptable to step away for an indeterminate amount of time, keeping the right to this place in line. The person who was “last” in line had to warn the next person who came over that, for example, “a woman in a yellow jacket has already occupied the place behind me” and thus confirm her right to her spot even if she did not come back until it was her turn.

Goods that did not exist in sufficient quantity for everyone were called deficit goods, or just “deficit.” In the 1970s and 1980s, salaries steadily rose, people started to have more money, and everything more or less valuable sold out quickly. Correspondingly, the scope of “deficit” widened. Salespeople took advantage of this and started selling deficit goods “through the back door” or “on the side.” For their part, shoppers initiated personal acquaintances with salespeople in order to buy items by avoiding the shop counter. Such an action was known by a different verb: “to come by something;” this meant to receive something that was not openly on sale. To be able to “come by” something, people usually paid not just with money, but with something else, even a service that had a connection to the “deficit.” This system of relationships was captured in the popular proverb “You—to me, me—to you”; as a result, everyone turned out to be interested in the deficit.

Nevertheless, stores needed to put at least a portion of the merchandise on the open market. And when it became known that a batch of “deficit” had arrived at a store (for example, jeans) and would go on sale in the morning, a line would already start forming the night before. So that people did not stand in line all night, lists were established. Anyone who wanted to could sign up for the line and then get a number.

Today, in this time of abundant goods, the classic Soviet type of line with lists for deficit items is no longer relevant; nevertheless, there are vestiges of it. Thus in municipal medical clinics in front of the doctor’s office there often arise conflicts about how to form the line: according to the time indicated on the voucher (“by registration”) or in the order of arrival (“live”).

And the longstanding debate about how exactly to word the question—“Who’s last?” or “Who’s at the end?”— is still a vibrant one. During Soviet times, only the first form was standard; the second was considered an indication of provincialism and lack of manners. Today, devotees of the second form have gone on the offensive, arguing that the word “last” has disparaging overtones, and addressing someone that way is degrading. There are additional arguments: pilots, for example, never say “the last flight” out of superstition (so the trip does not become the very last one). Nevertheless, nowadays it is more common to hear, “Who’s last? I’m behind you.”

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox