Leveraging India’s strategic autonomy

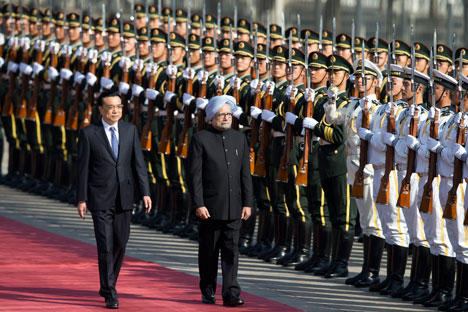

Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh is accompanied by Chinese Premier Li Keqiang as they inspect an honor guard during a welcome ceremony outside the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, China on October 23, 2013. Source: AP

The curtain is coming down on the Manmohan Singh era in India’s politics. The visit to China marks the prime minister’s last major foreign policy venture. This has been within a month of his visit to Washington. Dr. Singh’s twin foreign-policy priorities have been India’s relations with the United States and China and to a great extent they are inter-linked as well.

The high noon of Dr. Singh’s foreign-policy record was the signing of the US-India civil nuclear cooperation agreement in 2008. That was the only occasion when Dr. Singh showed an iron-mettle to ram through something he really wanted to get done on the foreign policy arena. Dr. Singh staked the survival of his coalition government and reworked the alignments in India’s domestic politics. For a leader billed as “accidental politician,” that was extraordinarily audacious.

Put differently, Dr. Singh never cared to hide that his number one foreign-policy priority was to build up a solid strategic partnership with the US as the anchor sheet of “emerging India.” Looking back, however, circumstances frustrated his efforts. The nuclear deal, which was supposed to be the flag carrier of the strategic partnership, failed to bring the expected windfall in electricity production or facilitate India’s admission to technology control regimes.

A number of factors crated the headwind – primarily, President Barack Obama presidency’s accent on nuclear non-proliferation and disarmament; economic crisis in the US; dissipation of India’s “growth story”; dented credibility of the Indian government as a result of corruption scandals and uncertainties in the run up to the 2014 poll and so on. At any rate, there has been a scaling down of expectations, which was evident during Dr. Singh’s visit to the US.

Meanwhile, the defence initiative unveiled during Dr. Singh’s visit stands out. It builds on the steady upward curve in military cooperation since 2005, which has become quite dense already. The defence initiative becomes Dr. Singh’s legacy insofar as the Obama administration has, finally, begun amending domestic legislation to enter into high-tech cooperation with India.

Indeed, the defence initiative is crucial to India’s calibration of ties with China. India marks a certain studied aloofness from the US’ rebalance strategy but has not rejected it, either. The ambivalence over the establishment of US military bases in Afghanistan is symptomatic of it. The point is, there are subplots. Across the board China has outpaced India and the asymmetry of power is only increasing. China is so dramatically building up its relations with the ASEAN region that India’s “Look East” policy begins to look provincial. The uncertainties about the US’ role in the Asia-Pacific are helping China insofar as the regional states hedge their bets, while on the other hand, India simply lacks the capacity to promote its own regional partnerships.

The heart of the matter is that Indian diplomacy with China has been reduced to one of managing the volatile ties. The US-India nuclear deal contributed to that volatility because the strategic statement of the deal and the hugely improper idea that New Delhi simultaneously probed on a parallel track – “quadrilateral alliance” with the US, Japan, Australia and India – set China’s back up. Most certainly, if a finger is to be put on where things began going wrong, it should be on the 2005-2008 period following the signing of a ten-year defence relationship between India and the US (known as the “New Framework for the US-India Defence Relationship”) and the commencement of negotiations over the nuclear deal. The WikiLeaks disclosed that the George W. Bush administration harbored grand military and strategic calculations underlying the 2005 defence framework in terms of the sheer size of the Indian market or weapons imports (estimated by US diplomats as worth exceeding $27 billion in the “near term” alone) and the prospect of a closer working relationship (“interoperability”) with the Indian armed forces in the Asian region.

Therefore, one cannot exaggerate the outcome of Dr. Singh’s visit to Beijing last week. The two bright ideas on the economic side – creating a Chinese industrial park in India and examining the feasibility of a Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar economic corridor – have gestation period and cannot address the massive trade imbalance in a near future. As for the Border Defence Cooperation Agreement, Defence Minister A. K. Antony has done the right thing by introducing a sense of realism by saying, “The fact that we have agreed on a certain set of procedures, mechanism, does not mean nothing will happen in the border. But with the agreement now, if something happens, then there are mechanisms to immediately intervene and find solution… there will be more contacts between the two militaries… The idea is to develop more trust between the two militaries.” He was quick to add, however, that he isn’t a “prophet or an astrologer” to say there would be no more face-offs between the two militaries.

The probability of “incidents” happening is rather high, as India proceeds with the construction of new military infrastructure and with the deployment of additional troops on the Line of Actual Control. Today, it becomes apparent that the centrality attributed to the strategic partnership with the US in India’s foreign policy has not helped to ease India-China tensions. Of course, India could and should have paid far greater attention to prevent the deterioration of its regional position. That should have been the real focus of foreign policy at a time of great fluidity in world politics.

On another plane, the history of Russia-China relationship holds important lessons for India-China relations. Three decades of protracted and unproductive border talks between the former Soviet Union and China finally could be brought to a close and a fruitful and mutually satisfactory agreement followed only when trust and confidence began appearing in the overall relationship. The trajectory of the relationship since began scaling strategic heights and is at an unprecedented level today.

This is where India should use more purposively the RIC forum [Russia-India-China] to give verve to relations with China. For this to happen, without doubt, much greater content also needs to be built into the traditional India-Russia strategic understanding. Suffice to say, the legacy of counting on Washington’s strategic choices to affect the region’s dynamics has not served India well to leverage the diplomatic space available to it in a rapidly evolving international milieu.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox