Nikita Khrushchev on early Russian impressions of India

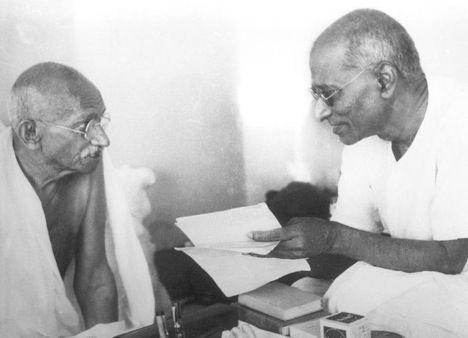

Nikita Khrushchev and Jawaharlal Nehru. Source: AP

After World War II, as Russia and the West both tried to influence the newly independent nations of the world, Moscow found itself at a handicap. This was because unlike the western countries – which had been colonising the world for over three centuries and were thus well-acquainted with far flung corners of the planet – Russian leaders and diplomats had very little experience in dealing with foreign nationalities.

One of the first major countries that Russians courted was India. But if Russia was an enigma wrapped in a riddle to the West, then India was equally mysterious to the Russians. In his memoirs, Russian leader Nikita Khrushchev writes, “Our knowledge of India was not only superficial but downright primitive.”

Firstly, like any right thinking people, the Russians, who had smashed the German forces after a titanic struggle involving tens of millions of armed men and women, couldn’t understand what Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru was up to with his policy of non-violence.

“We regarded the policies Nehru was pursuing as something close to pacifism. The teachings of Gandhi about non-resistance to evil and his other statements along the same lines, in the spirit of Leo Tolstoy, were not attractive to us,” Khrushchev writes. “We valued Gandhi’s nobility of spirit, but we didn’t understand him. In today’s world, we felt, it was impossible to win freedom by such methods.”

However, the British were cunning. Realising that a violent rebellion by India’s armed forces and revolutionaries was coming, and knowing Gandhi couldn't save them this time, the British agreed to retreat from India, dumping all credit on Gandhi and his non-violence. The British retreat sort of legitimised the theory of non-violence, and Nehru’s policies found takers in many developing countries. “At that point, whether we wanted to or not, we had to listen more closely to what the leaders of the Indian people were saying,” writes Khrushchev.

However, an official Russian visit to India did not materialise until 1955 – eight years after Indian independence. The first reason was Joseph Stalin, the Soviet dictator. Khrushchev writes: “In conversations between Politburo members and Stalin, the question of our relations with India was often brought up, but Stalin paid no special attention to India, a disregard that was undeserved. A country like that ought to have attracted his attention. He underestimated its importance and evidently didn’t understand the events taking place there. The first time Stalin began to pay close attention to India was after it won its independence.”

The second reason was Nehru, who at that time preferred to deal with newly independent nations such as China, Indonesia, Egypt and Myanmar.

Thirdly, Russian observers had come to the conclusion that India had chosen the capitalist path of development. “There was nothing to indicate socialist construction in that country. And we felt repelled by that,” Khrushchev writes.

Russian leaders also distrusted Nehru because he was palling around with the British, the same people who had murdered no less than 80 million Indians through artificial famines and wars. “We couldn’t understand why he took such a patient and tolerant attitude toward the British, who had formerly enslaved his country. British officers continued to serve in the Indian army, and British officials still held posts here and there in India. That put us on our guard,” Khrushchev writes.

The Russian way was the opposite. “They say that the Russian soul is like this: if you’re going to drink, then drink your fill; if you’re going on a binge, go all out; and if you’re going to fight, then fight till you win.”

On the positive side, even as leaders like Nehru were seen by the Russians – as well as the Chinese – as working in cahoots with the British, they were sympathetic towards Indians. “Unquestionably the Indian people enjoyed special respect in the USSR because they had formerly been oppressed by the colonialists and had now achieved their liberation,” the Russian strongman writes.

The move towards establishing closer relationships was drawn out. Finally, in June 1955 Nehru accompanied by his daughter, Indira Gandhi, made an official visit to Russia our county. “We showed Nehru everything that he wanted to see. In doing this, we had certain reasons of our own. We wanted him to see everything as it actually was, without embellishments. Of course we wanted him to see the best things and to have a favourable impression of our Soviet land. We wanted him to see how, guided by Marxist-Leninist theory, we had put that theory into practice, and what results we had achieved in building socialism. After all, this was our opportunity to show him such things concretely.”

Nehru travelled around and saw a significant part of the USSR, including Central Asia and other places.

“My impression was that he had a high regard for our achievements. We also had official talks with him. These went splendidly.”

However, Nehru, with his confused mind, couldn’t decide whether it was capitalism or socialism was better, or whether ties with the United States or Soviet Russia were good for India.

Nehru hadn’t budged from his mixed-economy theory. “As a result our former attitude toward Nehru did not fundamentally change,” writes Khrushchev. “As before, we viewed him with great respect and valued him highly, but in our view he was a man with a particular frame of mind, a particular culture, and particular views, and essentially that was correct.”

Khrushchev brilliantly concluded that “the path Nehru chose for the betterment of his country was a very long and slow one, and no one knew where it would lead.” And how prescient! The Russians, and indeed all of Asia, saw the contrast in achievements made by China to the small gains made by India. “That is, for all of Asia, including India, China should serve as the example, because in a short time it had achieved so much. The Indians themselves realised that China was moving ahead of them.”

“We wanted India to develop heavy industry and raise the living standards of its people, but not by the methods and policies that Nehru was proclaiming, because such goals were not achievable that way, and the people of India would be doomed for many years to an impoverished existence.”

Clearly, Khrushchev knew economics better than the lotus eating Nehru.

One can detect a deep disappointment in Khrushchev’s tone: “Outwardly our official talks with Nehru went smoothly. He praised Soviet achievements, but not once did he say anything to the effect that our experience might to some extent be transferable to Indian conditions, and he gave us reason to think that this was not what he wanted. For our part, we didn’t make a peep about such things because we didn’t want to be imposing our view of the world on him.”

Later Nehru invited an official delegation from Russia to visit India. The stage was set for new beginnings.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox