The Russians are coming!

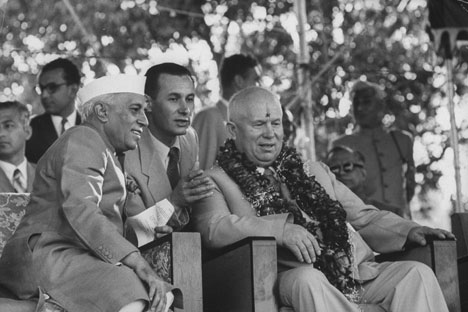

Jawaharlal Nehru and Nikita Khrushchev during his first official visit to India in 1955. Source: Getty Images / Fotobank

Nikita Khrushchev and Nikolai Bulganin led the first official Russian visit to India, in November-December 1955. Wanting to impress their hosts, Khrushchev brought along a substantial delegation, comprising representatives of the USSR Foreign Ministry and Central Asian republics.

The Russians were blown away by the reception in New Delhi. “Our welcome was incredible, with the warmest, friendliest, most benevolent and fraternal attitude being expressed toward the new arrivals. We saw nothing like this in any other country on the part of the people and Prime Minister (Jawaharlal Nehru),” Khrushchev writes in his memoirs.

The Russians were housed at Rashtrapati Bhavan, the figurehead President’s official residence. The visitors encountered some unexpected hostility on day one. President Rajendra Prasad’s attitude toward the delegation was very unfriendly. An altogether gloomy character, Prasad was also very religious and was upset by the fact that communists and meat eaters were being housed in the presidential palace.

Prasad’s views were conveyed to Khrushchev: “They have put the Russians there, and they are going to make a foul mess of my palace. They are going to eat meat there, not to mention drink alcohol.”

Perhaps believing that Russians couldn’t live without alcoholic drinks, Nehru arranged a special room hidden behind curtains where all sorts of drinks such as vodka, cognac and champagne were kept for the visitors if they wished.

However, Khrushchev conveyed to Nehru: “You can shut down that room. We’re not going in there. We’re very happy to accept your ways and customs.”

Khrushchev adds: “None of us of course wore a path to that little room. I forbade everyone even to look in that direction.”

After an address before the Indian Parliament, Khrushchev led the Russians on a trip around the country.

In Mumbai, as the delegation drove out from the airport, so many people came out to greet the Russians that the streets were jammed full. “We literally had to inch our way through the crowds. People jumped onto the cars in which we were riding, stood on the running boards, reached out their hands to touch our clothing. In the end such a large number of people had piled up on the car that they weighed it down and put it out of commission.”

The security team quickly got the VIPs into a police van with iron bars! When they reached the official residence, they found people camped out outside, shouting Hindi Russi Bhai Bhai. They sat there all night, chanting the same slogan, and dispersed only in the morning.

The next stop was Chennai. The Russians noted that it was “a very clean city, as most seaside cities are in general....We found ourselves in a fantastic world”.

At a concert in the city, Khrushchev found himself sitting with an elderly man, who “walked around in a kind of loincloth without a shirt”.

The man began to give an account of his understanding of India’s future path of development. “He argued that India should not take the Soviet Union as an example for its development; that large factories could not be built in India; that industrialisation in general was not a good thing for India. In his opinion, if large factories were brought into this heavily populated country, the high level of mechanisation and automation would result in a mass of working people being driven into the army of the unemployed, and poverty would only increase. He stuck to the Gandhian ideal: the spinning wheel was the only industry needed.”

The man was none other than C. Rajagopalachari, who founded the pro-private enterprise Swatantra Party. Considering such were the backers of private enterprise, it is no wonder India had to wait 35 more years for Prime Minister P.V. Narasimha Rao to kickstart economic liberalisation.

Colonial line

One area where Russians and Indians found common ground was in blasting colonialism. “We pointed out that the disastrous situation in which the Indian people found themselves was the result of many years under colonial oppression, the result of being robbed by the colonialist monopolies, who achieved their prosperity at the expense of the people,” Khrushchev writes. “These ideas were very well received everywhere. As soon as we began talking about them, the people would cheer us loudly. The anti-colonialist trend of our speeches was not phrased abstractly but was directed specifically against the British colonialists.”

However, Nehru and his daughter Indira did not approve of this direct attack on the British. “They didn’t say anything to us, nor did they indicate in any way that we were abusing their hospitality by presenting our ideas. But we sensed that (that was their attitude). Nevertheless we continued to make sharply pointed speeches as before, and the people liked it.”

Again, this is a pointer to the Nehru-Gandhi family’s disconnect with the Indian people. Most Indians instinctively dislike the British but Nehru was an Anglophile.

Indeed, Khrushchev comments on this aspect: “When we travelled around India, we encountered monuments along the way that had been erected by the colonisers in honour of their victories and their seizures of various territories in India. These were statues of various military commanders, both of naval and of ground forces, or other representatives of the British crown. And all these statues somehow got along with the world around them.

“The Indians are an amazing people; their patience is unbelievable. From our point of view we wondered how they could put up with these statues, which were constant reminders of their loss of independence and the oppression of their country by the British colonialists.

“After the revolution in our country we knocked down almost all the old statues. We left only a few with appropriate inscriptions as reminders of what our former oppressors had been like.”

To be sure, Nehru while not quite wanting to erase all traces of British colonialism had made cosmetic changes. New Delhi’s Kingsway was renamed Rajpath and Queensway was changed to Janpath just before the Russians landed.

Leaning towards India

The delegation then moved to Srinagar, Kashmir, where Khrushchev in his speech unequivocally backed India over Pakistan. This was a bit tricky for the Russians. “We didn’t want to complicate relations between India and Pakistan by our presence in Kashmir, nor did we want to link ourselves with India’s claims to Kashmir. We felt it was better for us to take a neutral position. Let them work out these disputed questions among themselves. The Indians made an especially emphatic appeal to us to support their position, but we were not impressed by that at all. On the other hand we didn’t want to cause distress for Nehru by our refusal. Our sympathies were on his side, on the side of India, if only because India had taken an intelligent position on international questions, did not belong to any military bloc, and had a sympathetic attitude toward the Soviet Union.”

“Our position in solidarity with the Indians in their dispute with Pakistan contributed even more to the strengthening of friendly relations between the Soviet Union and India.”

Upon coming to know of the speech, Indira called Khrushchev and said Nehru greatly appreciated the Russian support.

The Russia-India relationship was beginning to take a friendly shape.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox