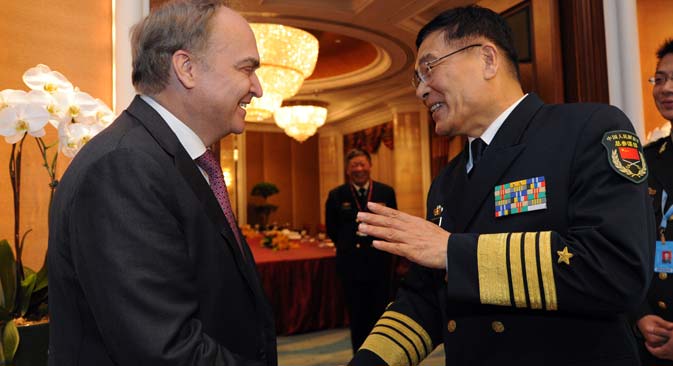

Admiral Sun Jianguo (R), vice chief of staff of China's People's Liberation Army (PLA), meets with Russian Deputy Defense Minister Anatoly Antonov on the sidelines of the 14th Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore, on May 30, 2015. Source: Photoshot/Vostock Photo

Held annually by the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), the Shangri-La Dialogue (SLD) has established itself as the main forum for discussing security issues in the Asia-Pacific. It has become similar to the Munich Security Conference in Europe in the sense that observers always pay much attention to who says what, using the gathering as a barometer for regional trends and developments.

While last year the event of the season precluding the SLD was the China-Vietnam oil rig crisis, this time the context is somewhat different in form, but much the same in essence. The first months of 2015 brought almost weekly updates on new land reclamation activities on the reefs, shoals and islands of the South China Sea. Unlike last year’s explosive crisis, the construction works are more of a scaring tactic. This doesn’t make them legal, but it gives China (and other builder states) a moral argument of being a victim of provocation, should any of the other claimants or any outside power (namely the U.S.) try to demonstrate its denial of the right to build.

Ironically, Beijing’s shift to a more subtle strategy did not make the SLD an easier venue for the Chinese delegation to attend. U.S. Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter in his address was highly critical of China’s reclamation activities and attending experts witness that the country’s representatives got a lot of tough questions over the three days of the conference. It once again seemed like China was a besieged fortress, feared and bashed by neighboring countries small and large.

Though many are worried by China’s alleged expansion, the Asia- Pacific has actually been performing rather well in keeping its own stability. Still, the question of whether China can rise peacefully remains. It seems that the gap between China and U.S. on one hand and the rest of the resident powers on the other is so big that any kind of regional order will clearly be based on the balance of influence between the two. But as the keynote speaker of this year’s SLD Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong noted, it may be a system “where major powers strengthen their influence within a set of international rules and norms” and it may be one without such rules.

In this sense Asia is very similar to the rest of the world. The fight is not about who gets what, but rather about what are states allowed to do to get what they want. We have to acknowledge that wanting something, having interests is normal for a state. And it is as normal for other states to want something completely different. Competition and divergence will be happening time and time again, but there must be rules for managing these differences. The key here is to make sure that using force to safeguard a certain interest is more costly than engaging in meaningful negotiations.

For the time being, China seems to value its functional relationships with other Asian states more than local territorial ambitions. Harmony - a central concept in Chinese political philosophy - seems to be the ultimate projection Beijing is trying to make. However, it is unclear whether this harmony implies that the others have a say in regional politics or it simply means that they are all supposed to surrender to Chinese dominance.

In a recent doctoral thesis Sungwon Kim coined the term ‘Eastphalia,’ suggesting that the Asian international order will be much different from the European, still largely based on the 1648 Westphalian Treaty. This fundamental document cements the principle of sovereignty equality, meaning that all states, big and small, are equal in their international status. It is quite clear that this is not the case in reality.

By comparison, the emerging Asian order may turn out to be quite the contrary. China may want to see its place at the top of the regional hierarchy, acknowledged as such by the rest. This is perhaps what Beijing means by naming the South China Sea a sphere of its “core interests.” It’s not about monopolizing control over the maritime trade routes or closing them off (that would be just plain silly). It’s about being the main overseer of order within the First island chain, feeling secure. This does not necessarily mean that the interests of neighboring states will be infringed upon.

Surely, not all will be happy with such an arrangement. Surrendering their security environment to the disposal of the Chinese is an unnerving idea for most of Asia and definitely a nightmare for the US. China’s policies towards its neighbors do not invoke much trust - an absolute ‘must’ for the sort of ‘harmony’ Beijing would perhaps like to see.

Here’s where Asia should start creating rules. The first rule is that if you want to solve your problems you have to start admitting them. Second, if someone has a problem with any of your actions (even if you consider them legal), stop for a moment and start talking it out. Third, be transparent about your intentions and your policies. This is exactly what German Defense Minister Ursula von der Leyen duly pointed out in her SLD address this year: “Believe me, it is not easy to open the books but we know that transparency is the key for trust and confidence”. Perhaps we can hope that Asia will be more successful in creating a functioning security architecture than Europe, and we will not see an Asian Ukraine.

Anton Tsvetov is the Media and Government Relations Manager at the Russian International Affairs Council (RIAC), a Moscow-based foreign policy think tank. He tweets on Asian affairs and Russian foreign policy at @antsvetov. The views expressed here are the author’s own and do not reflect those of RIAC.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox