Escape at dawn: When the Korean King sought Russian help

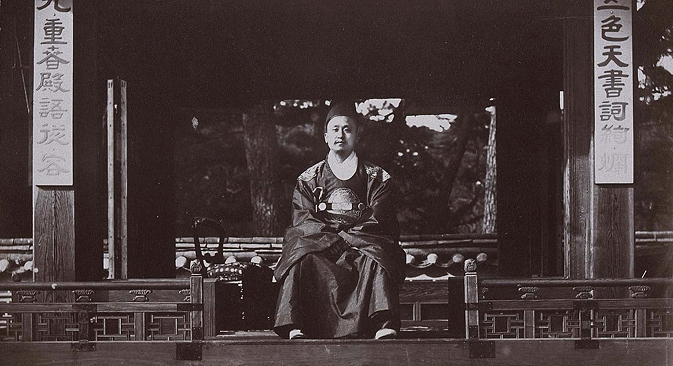

Fearful for his personal safety, a monarch of a sovereign nation chose to use the extra-territorial rights of a foreign legation and turn it into his own provisional headquarters. Spurce: Press photo

At dawn on February 11, 1896, two covered sedan chairs entered the gate of the Russian diplomatic legation in Seoul. Two people, dressed as female attendants of the Korean court descended from the chairs. The dresses were mere disguises. The guests were the Korean King Gojong and his heir-designate son Sunjong, who had fled the royal palace for safety.

This was an episode with few if any precedents in diplomatic history. Fearful for his personal safety, a monarch of a sovereign nation chose to use the extra-territorial rights of a foreign legation and turn it into his own provisional headquarters.

Admittedly, King Gojong had valid reasons to be concerned about his security. From 1894, Seoul came under Japanese military control (Japanese troops entered the city in the course of fighting the Sino-Japanese war). The Japanese installed a puppet government, which sidelined King Gojong and Queen Min. The queen, who was more resolute than her husband, tried to organize a resistance movement. The Japanese reacted by arranging her assassination in October 1895.

King Gojong and his son obviously feared that they might be next, and in search of escape routes, turned to the Russian Mission in Seoul. The Russian diplomats promised support.

The subsequent events are often represented by nationalist Russian historians as a perfect example of the peace-loving and selfless nature of Russian imperial foreign policy. This author, being a hard-nosed realist, believes that no country has ever practiced such selfless diplomacy, and in this particular case, there is little doubt that Russian actions were driven by realpolitik.

Russia rightly saw Japan at its major rival in the Far East and wanted to keep Korea beyond Japanese influence.

The escape of the king and his heir was arranged and for the following twelve months they remained behind the walls of the Russian Mission, protected by the Russian marines

To provide his majesty with the necessary living space, the building’s floor plan was rearranged. The king was given the best two rooms in the building and a special wooden house was built in a hurry to house the royal kitchen. At the same time, the courtyard of the mission was taken over by several government ministries. The concubines were present, too – and Russian diplomatic wives euphemistically described them as ‘ladies-in-waiting’ (it was the late Victorian era, after all).

All practical arrangements were supervised by Miss Sontag, a distant relative and household manager of Karl Weber, the former Russian envoy to Korea. Weber by that time had effectively finished his assignment terms, but due to the tense political situation and his experience, remained in Korea together with the new envoy.

Among other things, it is widely believed that Sontag introduced King Gojong to the art of coffee drinking. Recent research has demonstrated that the king had drunk coffee before, but nonetheless he became a committed fan only after his stay in the mission.

During his stay in the legation, the king rejected some notoriously pro-Japanese decisions of the earlier cabinet and, predictably, made some concessions to the Russians – even though most of these concessions proved to be short-lived (like the decision to entrust instruction of new Korean military units to the Russians).

These concessions and the generally unprecedented situation soon began to annoy many Koreans. They understood the need for security, but they were not happy to see their king becoming the permanent resident of a foreign mission. After some negotiations to ensure the personal security of the royal family, King Gojong left the legation on February 20,1897, thus ending this unique episode.

First published by RBTH Asia

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox