How the Russian Orthodox Church survived in Korea under Japanese rule

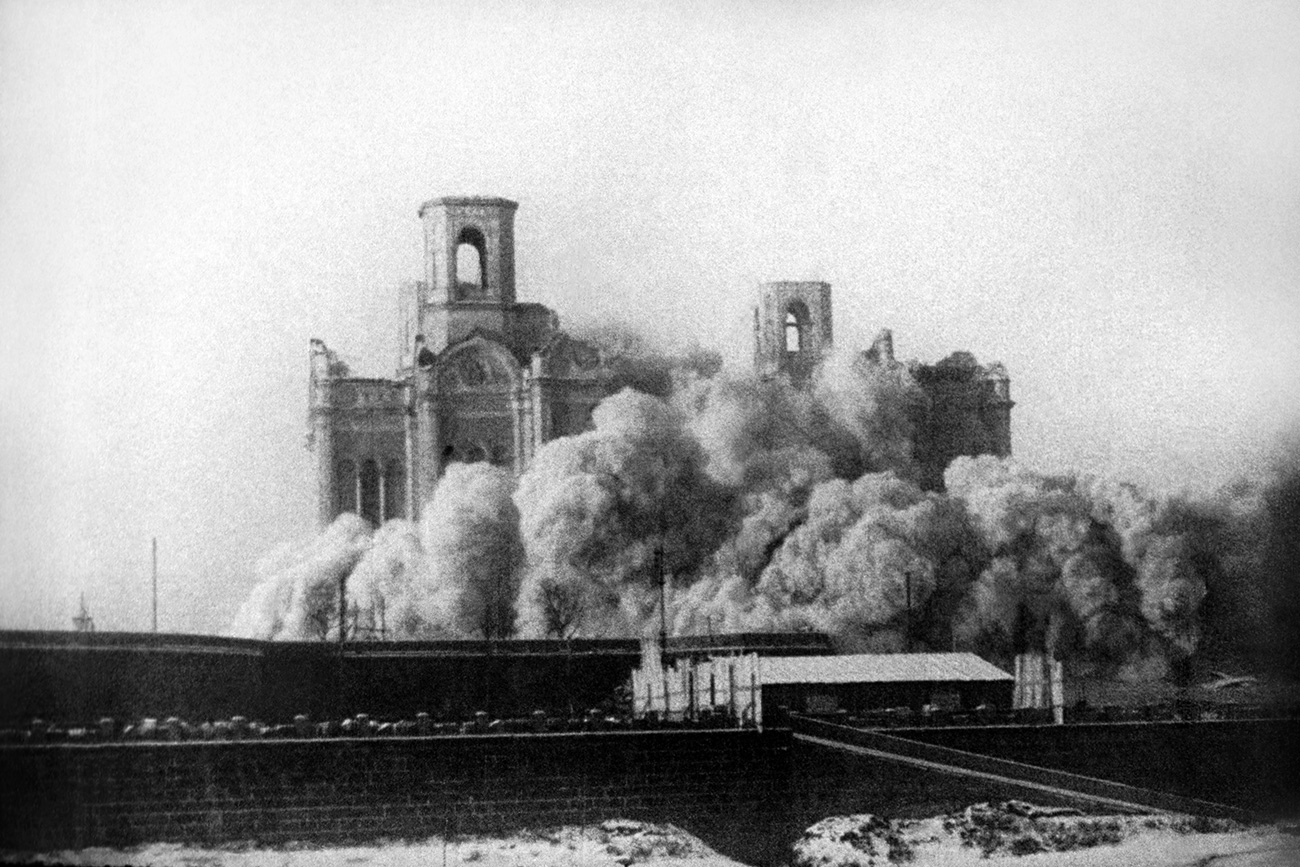

The Russian Orthodox Church was safe from a Bolshevik onslaught in Korea. Pictured above is the destruction of the Cathedral of Christ the Savior in Moscow in 1931.

TASSThe Russian Orthodox mission was officially established in Seoul in 1897, but after the 1917 October Revolution it lost its government subsidies and found itself in a very precarious situation. The official standing of the Russian Orthodox Mission in 1917-45 was somewhat unclear.

It survived largely by renting out its property, but was also occasionally helped by the Japanese Orthodox Church. It was effectively a subordinate of the Japanese Orthodox Church, but it had significant operational autonomy.

Therefore nowadays it is often claimed by the church’s historians that the mission has de jure remained a part of the Moscow Patriarchy throughout the entire colonial period.

One must keep in mind, however, that these claims relate to the intricacies of current church politics (for which this blog has no space to discuss).

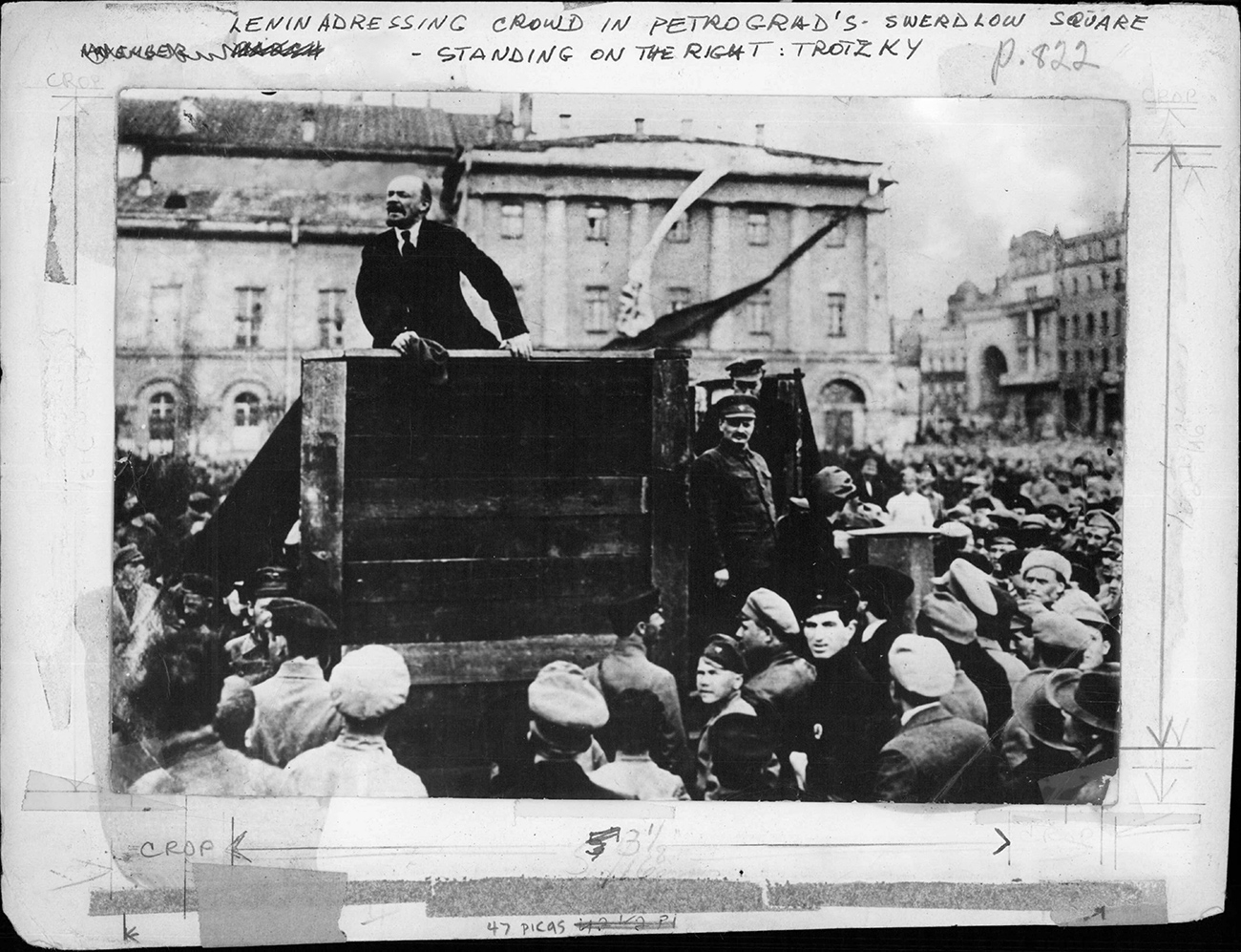

Reds and Whites

The presence of the Orthodox Mission was tolerated by the colonial authorities who saw the staunchly anti-communist Russian priesthood as a useful, if not an especially powerful political ally in Tokyo’s rivalry with ‘Red Moscow’.

Nonetheless, the colonial authorities were quite suspicious of Christian evangelism.

Therefore, most of the activities of the mission were concentrated on the Russian community in Seoul. This community was quite large, since in the early 1920s many supporters of the defeated anti-communist resistance had moved to Korea. Most of them soon left, but from the late 1920s until 1945, Korea was home to a few hundred Russians.

In 1925, Japan established diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union and as a result, a Soviet consulate was opened in Seoul. Predictably, the relations between the mission and the consulate were openly hostile – it did not help that these institutions were located nearby.

Physical confrontations were not unheard of, especially among ‘Red’ and ‘White’ children.

Evangelical activities

In spite of the Japanese colonial administration’s general disapproval of Christian evangelicalism, the mission was able to continue these activities at a small degree.

By 1930, there were a thousand Orthodox converts among the population of Korea, and several hundred more were welcomed to the faith in the 1930s.

With the beginning of the Second World War, the Japanese authorities became especially suspicious. The priests were banned form going to the countryside to meet their flock and general contacts with Koreans were discouraged.

Nonetheless, Orthodox Christianity was tolerated to a certain extent. Unlike their Western colleagues, Orthodox priests were not expelled from the country in 1941.

After the liberation of Korea in 1945, the Moscow Patriarchy briefly re-established control over the mission. By that time, the Soviet government had significantly softened its once militantly atheistic attitude toward the church and had even begun to see it as a marginally useful ally, whose authority could be utilized for nationalistic political mobilization.

However, the small Orthodox community of Korea soon found itself plagued by Cold War controversies.

And quiet flows the Han is a blog about the historical and contemporary interactions between Russians and Koreans. In most cases, but by no means always, political issues are studiously avoided by the author, whose major interest is everyday life, culture and the lives of individuals. In this blog, Dr. Andrei Lankov explores how Russian culture was (and is) seen in Korea. He talks about migration, inter-marriage and even cuisine.

Dr. Andrei Lankov, born in 1963, is a historian specializing in Korea. He is also known for his journalistic writings on Korean history. He has published a number of books (four in English) on Korean history. Having taught Korean history at the Australian National University, he now teaches in Kookmin University in Seoul.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox