An eccentric American opens a design engineering bureau in Moscow

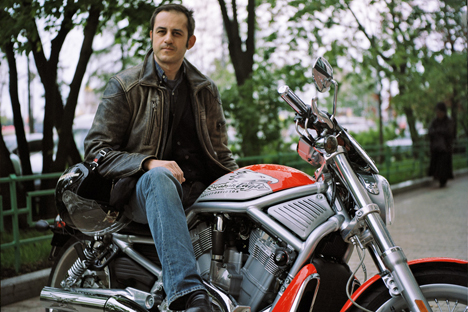

It seems the image of a principled eccentric went down well with the local customers. Source: Kommersant

“Hi, Gabrio!” a Russian traffic cop yells, waving to a Harley-Davidson flying down Kutuzovsky Prospect. When the motorcyclist slows down at the traffic lights, a small Chihuahua in a pink helmet and pink glasses sticks her head out of the bag that the rider is wearing on his chest. Children wave to the dog cheerfully from the windows of cars around him.

The motorcyclist’s name is Gabrio Marchetti, and he is on his way to his design-engineering bureau to conduct important negotiations. He will need his image of a slightly eccentric foreigner there.

It was his eccentricity and passion for adventure that originally brought Marchetti, an American of Italian descent, to Russia. He spent most of his life in the U.S., and he moved to Italy at the age of 23, following his mother’s decision.

Marchetti would have spent his life working as an engineer at CH2M HILL—one of the world’s largest engineering bureaus—if his boss had not been looking for an engineer to construct an Alcoa plant in Russia. The mission was for three months only, and Marchetti was so excited about it that he even settled for a salary lower than he was earning at the time.

That was in 2006, and Marchetti was sincerely expecting to see bears roaming in the streets of Moscow. Instead, he found girls wearing stiletto heels, stores operating around the clock, casinos bathing in the sea of night-lights, and the atmosphere of New York.

To cut a long story short, when his contract expired after three months, Marchetti asked to be sent to Russia for another project. He also managed to negotiate a salary three times higher than that of his first visit.

In 2008, CH2M HILL offered Marchetti work on a project in Italy, but it was soon suspended because of the crisis. Marchetti had been deliberating on whether to stay in Italy or go to Russia, when he met his former colleague, Giuseppe Santaniello.

“If you stay in Italy, you will remain an employee for the rest of your life. Let us try starting our own business instead,” Santaniello said. This was how Marchetti came back to Russia.

The partners invested $10,000 each and opened TGarbo—a design engineering bureau specializing in consulting, engineering and general contracting in construction. Their first expenditures were on company registration and advance payments to freelance specialists, after which they had nothing left to lease an office.

Thus, in their early days, the partners met customers at cafes—most often at a French place called Le Pain Quotidien on Kamergersky Lane. Its customers stared at the foreigners trying to negotiate million-ruble contracts, while the men at the next table discussed the quality of local rolls.

Yet it was hard to find contracts in the construction market, which had decreased by around 40 percent. For Marchetti, it was even harder because of his poor command of the language; he could understand only 60 percent of what was said in Russian.

As a result, he had to seek his potential customers among foreigners. The first contract was signed with the Italian company Mar, and his largest deal involved the American business John Deere (its representatives were former partners of Marchetti during his days at CH2M HILL).

This is when Marchetti realized he had never before really known all the peculiarities of local business practices. In the first place, from the beginning to the completion of any project, the customer has to obtain at least 500 signatures on his documents.

“Once, I counted the number of signatures, just to see for myself,” says Marchetti. “Five hundred signatures! And then there were all the seals and stamps!”

The sphere in which TGarbo operates is one of the most corruption-stricken in Russia—even Vladimir Putin mentioned this in his pre-election speeches. Without bribes, public officials refuse to issue required permits and do their best to delay construction terms.

However, Marchetti insists that many Western companies are ready to put up with all these delays, for the opportunity of doing their business in a fair way. In this aspect, Western businesses have more trust in foreign contractors, and Marchetti never fails to take advantage of that.

He recalls a case when some municipal official refused to issue a required permit without an “extra financial infusion.” The customer refused to pay a bribe, and the official was unwilling to sign the papers.

TGarbo invented a smart move for the customer: They reached an agreement with the prefect's office for the construction of a school, local papers published this news, and the public official could not find any more grounds to refuse issuing the required documents.

In addition, connections and relationship are extremely important in Russia. “You can offer anything to an architect. Regardless of the quality of your offer, he will certainly refuse unless you have already discussed all the details in an informal atmosphere,” Marchetti says, sharing his experience.

There is also the drinking problem; he remembers a time when he had scheduled a business meeting in the early morning, and his contractor brought along a bottle of cognac, suggesting they drink it immediately.

Several years ago, Marchetti and his expat friends went to a mountain ski resort in Switzerland, and he served them some piña coladas—which they really liked. A couple of years ago, one of these friends decided to open a restaurant and called it Gabrio.

Not only did Marchetti teach his friend to serve this cocktail, but he also repaired and furnished the restaurant himself.

After this, other potential customers contacted Gabrio. Finally, he decided to start Itatek—a company specializing in repairs and renovation for apartments and industrial buildings. Prices for the work start at €600 ($780) per square meter.

Related:

LiveJournal helps Muscovite find candy business

“For the Russian business community, formalities and flashiness are very important—wearing good watches, driving expensive cars and so forth,” says Marchetti. “There is no European country where you can meet so many people in ties as in Russia.”

Marchetti does not wear watches, arrives to business meetings by motorcycle or by metro, and prefers jeans to trousers.

Another part of this flashiness is being less than punctual, he says. In Italy, the higher an official’s position, the more punctual he is; in Russia, everything is vice versa. Marchetti recalls a customer whose house in Ostozhenka he refused to repair—simply because the owner was late all the time.

The annual turnover of Itatek and TGarbo is around €2 million ($2.6 million). It seems the image of a principled eccentric went down well with the local customers.

First published in Russian in Kommersant Secret Firmy

Read more about Russian start-ups

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox