Why a Russia-China currency swap agreement turned out to be a damp squib

A currency swap agreement between Russia and China seemed to be initially successful, but turned out to be ineffective.

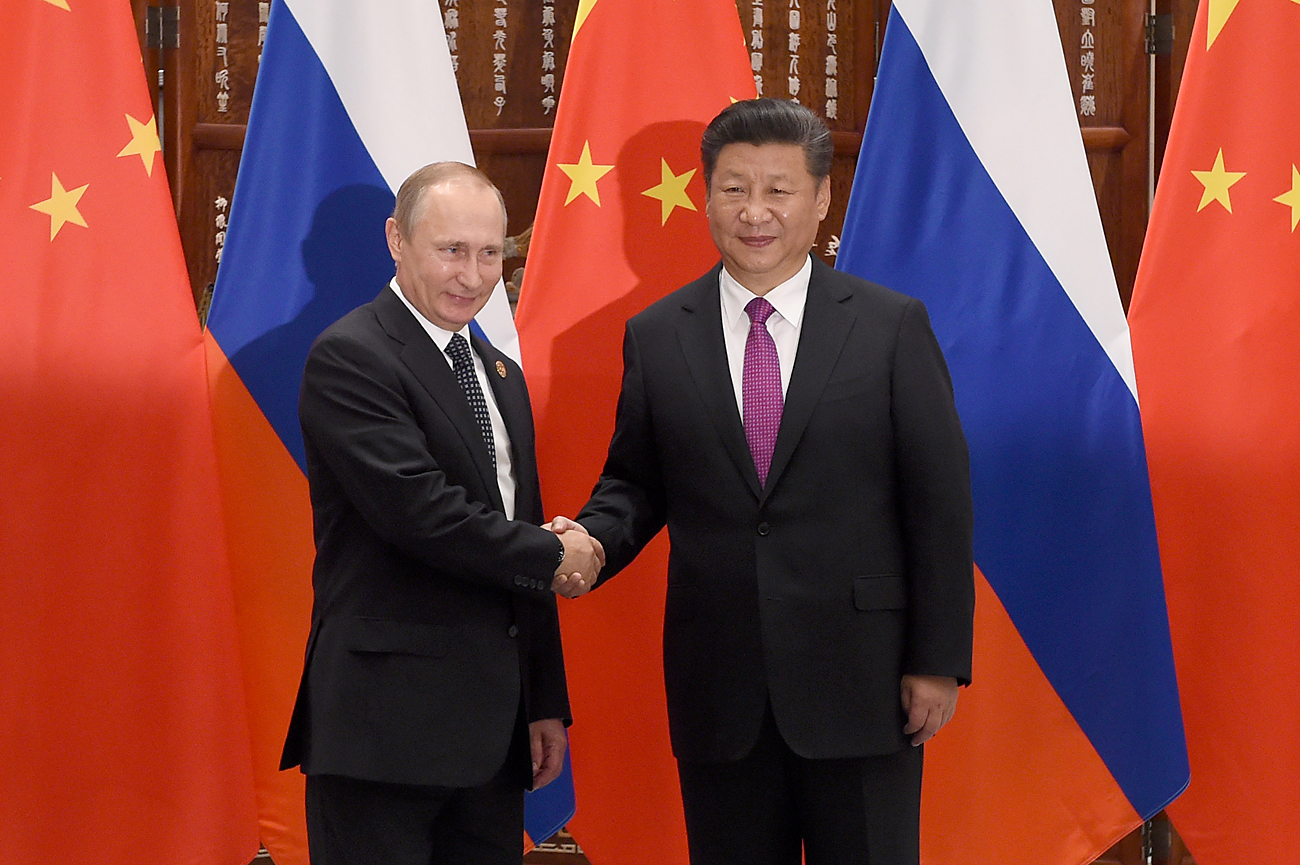

Sergey Guneev/RIA NovostiOne of the biggest hopes for a breakthrough in the Sino-Russian reapprochement after the 2014 Ukraine crisis and the first round of Western sanctions was a currency swap opened between the Central Bank of Russia and the People’s Bank of China.

Moscow and Beijing sealed a deal for almost $24.5 billion in order to boost bilateral trade and ensure mutual investment cooperation. The swap agreement is due to lapse in 2017, as it was opened for 3 years. It did not achieve the kind of success that Russia and China hoped for.

The swap agreement between China and Russia falls in line with Beijing’s efforts to internationalize the Renminbi (RMB) in recent years. All in all, China has sealed 32 (!) swap deals since 2009.

A currency swap agreement between Russia and China seemed to be a logical and useful idea for the development of bilateral trade. The value of the deal signed between China and Russia was comparatively big: 150 billion yuan.

Beijing signed larger agreements only with its major trade and investment partners: with the EU for 350 billion yuan, with Hong Kong for 400 billion yuan, and with South Korea for 360 billion yuan.

In 2014, the year the swap agreement between Russia and China was signed, the prospects for bilateral trade were quite bright. Moscow and Beijing aimed for $100 billion in bilateral trade in 2015 and wanted to double this amount by 2020.

However, the swap deal could not help improve the bilateral trade due to the depreciation of the ruble, which affected trade between Moscow and Beijing.

According to Chinese statistics, Sino-Russian trade turnover reached $88.4 billion in 2014, but then fell by almost 30 percent to $63.6 billion in 2015, and only slightly increased up to $69.5 billion in 2016.

Despite disappointing trade statistics, according to Russian President Vladimir Putin, mutual payments in national currencies between China and Russia have increased since the swap deal was signed. But nevertheless, such payments are mostly dominated by the RMB as the Russian ruble is used in just 3 percent of mutual transactions.

Ruble volatility and disproportional trade

It is important to point out, that Vladimir Putin’s recent statement is probably the only source of information on payments in national currencies between China and Russia.

“It is unclear, how many companies have actually used the mechanism of the swap agreement between China and Russia. It’s either expensive or risky. Most likely, it is all the fault of the excessive volatility of Russian currency,” says Alexander Gabuev, Chair of the Russia in the Asia-Pacific Program at the Carnegie Moscow Center.

The swap agreement cannot be of help in the general context of weak economic cooperation between Moscow and Beijing. “The key driver for the growth of bilateral trade and investment is the increase of demand for commodities and investment assets,” says Vasilii Nosov, senior analyst at the Center for Macroeconomic Research at Sberbank.

“Unfortunately, China’s demand for Russian goods and assets stays quite weak. The only Russian commodity China is really interested in is oil, but there is no reason to expect a sharp increase in supply.”

Sino-Russian trade stays quite disproportional, and no swap agreement is capable of altering this situation. Russian exports to China are overwhelmingly dominated (60 percent) by hydrocarbons, and Moscow is not even a top-10 trade partner of Beijing.

The trade imbalance between China and Russia (Beijing has been Moscow’s main economic partner in recent years) practically makes the swap deal quite useless.

“China is not interested in the ruble, so de facto, payments can only be performed in yuan. On the other hand, considering the fact that yuan is not a freely convertible currency, Russia can only use it in transactions with China,” Nosov adds.

Sagging Russia-China bilateral trade

The Sino-Russian swap agreement was signed right before a major crisis and the depreciation of the Russian currency. Although the idea of an escape from the U.S. dollar in bilateral payments is quite positive, the deal could not help improve bilateral trade and investment.

General economic cooperation and business relations between Moscow and Beijing stay quite weak and disproportional.

Under such circumstances, a swap agreement cannot operate in full capacity as it does, for example, between China and the EU, which had a trade turnover worth almost 515 billion euros in 2016. The agreement per se proves to be a useful tool for developing trade and covering risks.

However, it works at best only on the back of strong economic ties, which Russia and China do not enjoy.

RMB takes over the world

Sino-Russian steps to conduct mutual transactions in national currencies using swap deals are a part of Beijing’s widely discussed policy of internationalizing its currency. A Major breakthrough for establishing the yuan as an international currency happened in the end of 2016.

The IMF included the RMB to the SDR (Special Drawing Right) basket, making it one of the world reserve currencies along with the U.S. dollar, the British pound, the Japanese yen and the euro.

However, the actual usage of the RMB in international payments is relatively small for now. At the end of 2016 Chinese currency accounted for 1.68 percent of global transactions (while the U.S dollar was used in 42.1 percent of cases).

China’s active steps to internationalize its currency has led some analysts to assume that Beijing aims to act as a competitor to the U.S. on the global financial stage.

However, it is quite debatable whether Beijing is actually interested in shattering the dollar’s role as the world’s major reserve currency. Michael Pettis, professor of finance at Peking University and a specialist in China’s financial markets, in one of his articles proves that reserve currency status for the RMB is actually undesirable for China.

In this case Beijing would neither be able to keep a big trade surplus and nor avoid high unemployment and currency volatility risks, he argues.

Vita Spivak is Coordinator of the Russia in Asia-Pacific Region program at the Carnegie Moscow Center. Views expressed are personal.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox