Taking war into the skies: The age of the airship

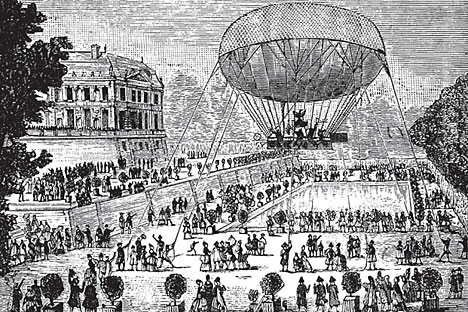

The Leppich’s hot air ballon test. Source: UllsteinBild / Vostock_photo

In the summer of 1812, an extraordinary construction appeared by Moscow. On the Vorontsovo estate, seven kilometers from the city, German engineer Franz Leppich led round-the-clock work on the creation of an unprecedented aircraft. Warfare was about to get airborne.

Sewn from thick fabric, Leppich’s huge inflatable oval was attached to a 20-meter wooden platform. Forty rowers were to use giant paddles to power the craft, which had gun mounts around its perimeter and compartments for fuse bombs.

The early blimp was meant to help the Russian Army halt Napoleon's invading forces, but it was plagued with problems. Above all, the material leaked and the paddles constantly broke. By the time the Russians finally turned and fought a bloody and inconclusive engagement with the invaders at the Battle of Borodino the device was still not ready and it was ultimately dismantled, its wooden platform burned and its designer disgraced.

And so the story of Russian military aeronautics began with a failure. But Leppich’s work was not forgotten. Throughout the 19th century there were attempts in Russia to create an aircraft lighter than air for military use.

The airship’s chance came again in 1854 when British warships blockaded the imperial capital St. Petersburg from the sea, preventing the weak Russian fleet from breaking out.

Army Lieutenant Ivan Mantsev proposed a simple and bold counter-measure, entailing the construction of several dozen airships which the wind would carry out to sea, allowing the crews to drop incendiary bombs on the wooden British ships. But time was against the plan and it was dropped.

Until the early 20th century, it was generally only isolated enthusiasts who still tinkered with airship design. The original idea of attacking the enemy from the air was not embraced by the Tsarist army, although in 1887 the idea was also taken up by the future father of Russian cosmonautics, Konstantin Tsiolkovsky.

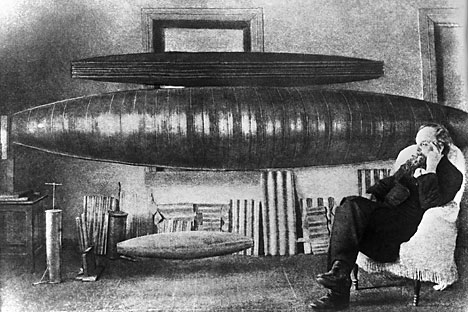

Konstantin Tsiolkovsky (1857-1935), Russian rocket scientist, pioneer of astronautic theory, at work. Source: ITAR-TASS

Even by today’s standards his airship design was ambitious: 200 meters long, it would be propelled at 25 mph by eight steam engines and would carry 200 people and 14 tons of cargo.

In 1898 engineer Konstantin Danilyevsky also built several pedal-powered airship models. But none of these projects got further than the drawing board.

After the turn of the century the Russian General Staff decided instead to stake its future on the development of planes and helicopters, which given the existing industrial base was a more complex and expensive option.

Consequently, when the Tsar’s forces desperately needed intelligence and air support in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905, repeated requests to St. Petersburg for airships went unanswered. After the war, though, the government purchased models from abroad while gradually building up its own construction capacity.

During the First World War, Russia built two airships, including the world's largest, the “Air Cruiser", which was 150 meters long and could fly at 50 mph. Including foreign-built models, the Russian Army deployed seven airships from 1914-1917, providing invaluable support to troops on the ground.

During the First World War, Russia built two airships, including the world's largest, the “Air Cruiser". Source: UllsteinBild / Vostock_photo

Having a greater range than planes and surpassing their load capacity, airships were widely used for reconnaissance and bombing. In the summer of 1915, Russian airships based in Brest-Litovsk carried out daily bombing raids on concentrations of enemy troops and railroad yards. The German command sent squadrons of fighter planes against them without any success.

Meanwhile, airships were also highly effective in determining weak points in the front lines, and in some cases even scattered special anti-cavalry spikes over large areas.

In the Soviet period, interest in airships tailed off. While they enjoyed a boom in the 1920s and 1930s, they were almost entirely supplanted by planes in the Second World War.

They were still irreplaceable in some tasks, however, like demining seaways and locating sunken ships and submarines. Three Soviet airships proved so successful in the latter task in the Bay of Sevastopol that the Black Sea Fleet command appealed to Moscow to send several more.

Although the era of the military airship finally came to an end after the war, the craft does not appear to have been consigned to the history books just yet, antiquated as it might now seem.

In 2013, the 55-meter-long AU-30 blimp built by the Russian company Augur RosAeroSystems took flight in the Vladimir Region. With a larger model capable of carrying 16 tons of cargo reportedly under development, the airship may yet re-emerge as a cheaper variant than helicopters and planes in such tasks as aerial photography and technical monitoring in the oil and gas industry.

An AU-30 zeppelin during a flight over the city of Kirzhach. Source: ITAR-TASS

The Russian military and border guards are also said to be interested in the potential use of airships to haul equipment over large distances and to monitor stretches of border that are vulnerable to drug trafficking.

Even if these plans come to nothing and a line is finally drawn under the age of the airship, the craft represented a vital progression in the history of Russia’s air power.

Alexander Vershinin is an historian and holds a Ph.D in History. He is a senior researcher at the Governance and Problem Analysis Center in Moscow.

Read more: Modern zeppelins may help develop Russia’s regions>>>

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox