The Obukhov State Plant: Funded from an engineer’s own pocket

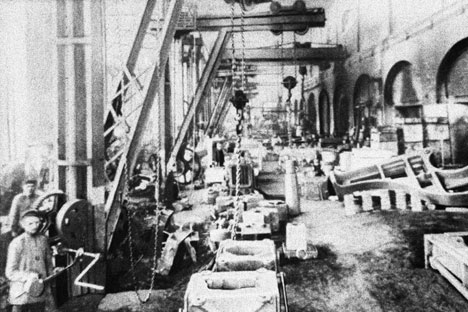

Inside the Obukhov Plant. Source: PhotoXPress

In the second half of the 19th century, Russia entered the era of modernization with only a handful of factories, all of them state-owned. However, the government could not ensure the rate of growth of industrial production required to drive on the economy and ensure the fighting capacity of Russia’s army.

So when in 1863 metallurgists Nikolai Putilov and Pavel Obukhov came to the Navy Department with a proposal to create a plant near St. Petersburg that would supply the fleet with rifled artillery guns, the initiative was enthusiastically received. Putilov invested his own capital in the project and Obukhov contributed the patent for the unique cast steel he had invented while working at the Zlatoust arms factory in the Urals.

The two men set themselves the ambitious goals of establishing a full production cycle from scratch and delivering one million rubles’ worth of weapons to the government in five years. Work began almost immediately in the marshland by the city to create one of the largest factories in the country. The planners thought well ahead in terms of the skilled workers that would be needed for the plant, and gave steel industry training to peasants from the outlying villages.

Soon named the Obukhov plant after one of its two main concessionaires, the company turned out its first products a year later. But since the costs proved to be higher than expected, the private owners had to turn to the state for assistance. After receiving a powerful financial boost, the Obukhov plant had by the start of the 1870s attained parity with the world's largest manufacturers of artillery weapons.

Bringing science to steel production

It was in St. Petersburg that a serious scientific approach was first taken to Russian steel production. To this end, the Obukhov management brought on board one of the greatest steelmakers of his time, Dmitry Chernov. Under his leadership the steel production process was tied to a clear formula, which in turn enabled breakthrough innovations such as the installation of open-hearth furnaces.

Obukhov Plant workshops in St.Petersburg, 1860s. Source: RIA Novosti

By 1872, the plant was already manufacturing the first Russian 305-mm heavy naval guns, production of which had previously been monopolized by the German company Krupp. In the 1880s, the plant also mastered the manufacture of a new kind of weapon, the torpedo. Other innovations included engines for the first aircraft prototypes in the world, built by Alexander Mozhaisky, armored plates for warships, artillery shells, rifle scopes, binoculars and a wide range of civilian products.

The government gave constant recognition to the Obukhov plant for its outstanding work and granted it, together with a few other select companies, the right to place the imperial double-headed eagle on its products. In 1886, it was accorded “strategic” status and in 1886 was nationalized by the state. In 1908, Tsar Nicholas II gave instructions for the plant to receive its own flag, and its products went on to win consistent acclaim at exhibitions in Paris, Philadelphia and Vienna, despite stiff competition from global armament giants like Krupp, France’s Creusot, and Britain’s Armstrong. The Obukhov plant was unrivaled on the Russian market, however, and in 1913 more than half of the imperial army’s land guns and more than 90 percent of Russia’s naval guns bore the Obukhov stamp.

New beginnings

The enterprise was given a new name and a new profile in the Soviet era: The "Bolshevik" plant in Petrograd (later renamed Leningrad) built tractors, aircraft engines, railway carriages and drive shafts for hydroelectric power stations. In the 1920s, the plant gradually mastered the production of a new generation of weapon – the tank, with the first Soviet tank the T-18 being built here. The plant’s weapons engineers were by now absolute masters of their trade and were duly combined in a separate design bureau.

Obukhov guns massively increased the might of the Soviet army on the eve of World War II, and from 1941-1945 the plant in Leningrad did not stop production for a single day, even during the 872-day siege of the northern city by Nazi forces. Its production lines also turned out thousands of shells and mines, while the plant workers built an additional 30 artillery batteries on railway platforms.

The 1941-1945 Great Patriotic War. Cannons melted in 1898 at the Obukhov plant in St. Petersburg installed on the top of the Eagle's Nest mountain during the 1904-1905 Russo-Japanese war. Soviet soldiers in liberated Port-Arthur, 1945. Source: N.Maximov / RIA Novosti

After the war, the industrial complex grew ever bigger and by mid-1987 employed more than 17,000 people in the development and production of a wide range of products for the navy, nuclear missile forces, and military space forces that depended on the missile industry. The 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union and the crisis of that decade dealt a major blow to production at the plant, causing output to plummet almost 30 times over.

The turnaround came at the start of the21st century with a decree signed in 2002 by Russian President Vladimir Putin, which added the plant to the Almaz-Antey air-defense concern. Today the main products of the Obukhov plant are surface-to-air (SAM) missile systems, including the world-famous and still unrivaled S-300 and the S-400 systems. Maintaining Russia’s edge in the SAM leagues, the two series will be followed up by the state-of-the-art S-500 system, which is already on the Obukhov drawing board.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox