Killing 2 birds with 1 stone: The Komsomolsk-on-Amur aircraft factory

Assembling the Su-35 in the shop at the Komsomolsk-on-Amur aviation plant. Source: Marina Lystseva / TASS

As the industrialisation of the Soviet Union gained pace in the early 1930s, the Russian Far East was still a virtually uninhabited wilderness in human terms. Fewer than a million people lived across a territory the size of Europe, while the phrase “economic development” barely applied anywhere. Nor were there any large industrial enterprises that could support the region's economy and military infrastructure, the need for which had been painfully demonstrated by the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905.

Without a strong industrial base it was impossible to win an armed confrontation at the country’s eastern borders, and it was this stark reality that pushed the Soviet leadership to revise its approach to the development of the Far East as it prepared for war with Germany and Japan.

Construction of the plant in the Amur taiga, 1930s. Source: The Komsomolsk-on-Amur aircraft factory

The idea of creating an ultramodern aircraft production facility in the Amur taiga forest was extremely bold, given the absence of human resources or developed transport and energy infrastructure. There was not enough in place to build the factory, let alone a city with apartment buildings, shops and hospitals that had to be built from nothing in just a few years. The only human settlement in the vicinity was the main encampment of the indigenous Nanai people, where factory buildings were now to be built in place of the animal skin tents, or yurts, in which they lived.

A rapid tempo was set for the fulfilment of the task. In January 1932, the government decided to build the aviation plant on the banks of the Amur River to form the heart of a future city. Within six months, the Communist Party had dispatched several thousand civilian workers and members of the Komsomol youth organization to their new place of work and residence in the Far East from the central regions of the Soviet Union.

Construction of the plant in the Amur taiga, 1930s. Source: The Komsomolsk-on-Amur aircraft factory

The nascent city was named Komsomolsk-on-Amur in their honor, while a discreet veil of silence was drawn over the assignment of several thousand prisoners to build the aircraft factory and surrounds.

Planes from the east for war in the west

In 1934, everything was ready for laying the foundation of one of the country's largest aviation plants, which turned out its first aircraft in just two years from its still uncompleted workshops. The work was driven on relentlessly since the looming conflict demanded a fast spike in production volumes. The first Komsomolsk-built product was the P-6 light reconnaissance aircraft, designed by a future star of Soviet aircraft design, Andrei Tupolev. However, the speciality of the far eastern engineers would be another aircraft, the DB-3, one of the first Soviet long-range bombers, which was created in the design bureau of Sergei Ilyushin, who won prominence in aviation before the Second World War. Soviet DB-3 pilots set world records performing non-stop flights from Moscow to the Far East and North America.

During the war, the DB-3 proved to be one of the most formidable fighting aircraft of the Red Army. This was the plane that on the night of August 8, 1941, mounted the first major bombing raid on Berlin, at a time when Soviet ground forces were retreating on all fronts. The Komsomolsk plant was one of the few centers of production of the aircraft, which after modernization became known as the Ilyushin Il-4.

The Tupolev R-6 on the Amur river, 1936-37. Source: The Komsomolsk-on-Amur aircraft factory

During the war, the Amur plant supplied almost 2,800 units to the front. However, the facility’s heyday did not come until the post-war years, when the country’s distant former backwoods grew into a huge center for the production of new combat aircraft, unrivaled by any others at the time.

The USSR’s fighter jet workshop

The plant was also given the daunting task of mastering the production of fundamentally new jet aircraft when no Soviet factory had the necessary experience in this field. The task involved restructuring the entire production chain amid an acute shortage of resources and a deterioration of relations between the USSR and the West that heralded the Cold War.

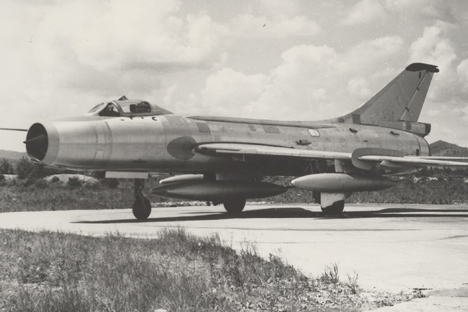

The Su-7MK. Source: The Komsomolsk-on-Amur aircraft factory

However, Komsomolsk rose to the challenge, and the first Soviet MiG-15 jet fighter rolled off the line in 1949. In the 1950s, the plant’s fate became inextricably linked with the work of the Sukhoi Design Bureau, and the resultant Su-7 became the first Soviet fighter plane to break the sound barrier.

The Su-17. Source: The Komsomolsk-on-Amur aircraft factory

This was followed by a series of outstanding “hits” from the enterprise: the Su-17, a pioneer among third-generation fighters, followed by the Su-27, the first fourth-generation fighter and its various modifications, the Su-27SK, Su 30MK, Su-33 and Su-35, which still form the backbone of many air forces in the world.

The Su-27 over the Amur river. Source: The Komsomolsk-on-Amur aircraft factory

The Su-27 has for many years been the primary product and specialization of the Komsomolsk plant, and since 2010 the company has been working on a new breakthrough development, a prototype of a fifth-generation fighter.

The aircraft, which has the working name of the T-50, has the potential to rival the only existing aircraft of this type, the U.S. F-22 Raptor.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox