Battleship Potemkin: What happened to the ship after the movie was over?

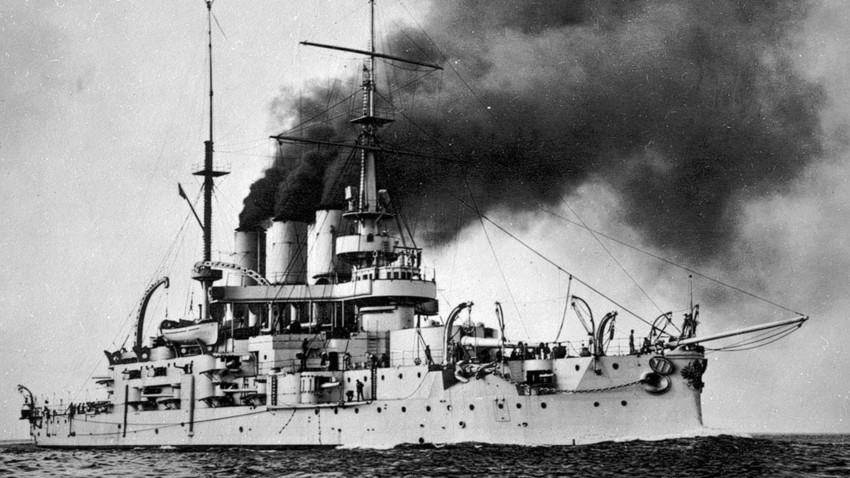

The Battleship Potemkin.

WikipediaA baby carriage with a child inside rolls down the steps as the crowd runs in panic from the soldiers firing at them… This scene, from Battleship Potemkin, is one of the most iconic in world cinema. The film is about a mutinous Russian naval ship during the Revolution of 1905, which shook the entire empire.

Imperial fleet

The Potemkin, which was the Russian Navy’s most powerful and modern ship at that time, stayed in the Black Sea port of Odessa after the

As a response to the government’s harsh measures, the Potemkin fired several shots, but nobody was killed. There was no major shelling from the revolutionary ship as many Odessa residents feared. Instead, the Potemkin left port and sailed towards the main group of the Black Sea Fleet that remained loyal to the Tsar, and which was approaching Odessa in order to deal with the rebellious ship. The mutiny appalled the authorities so much that they were ready to destroy this state-of-the-art vessel that had entered the fleet only a couple of months before.

Still from film "Battleship Potemkin" movie, 1925.

RIA NovostiWhen the opposing ships met, however, there was no battle. The Potemkin and 11 vessels of the

Joined by another battleship

This is the point at which Eisenstein’s movie ended. But, in real life, the Potemkin’s saga was far from over.

As it turned out, the

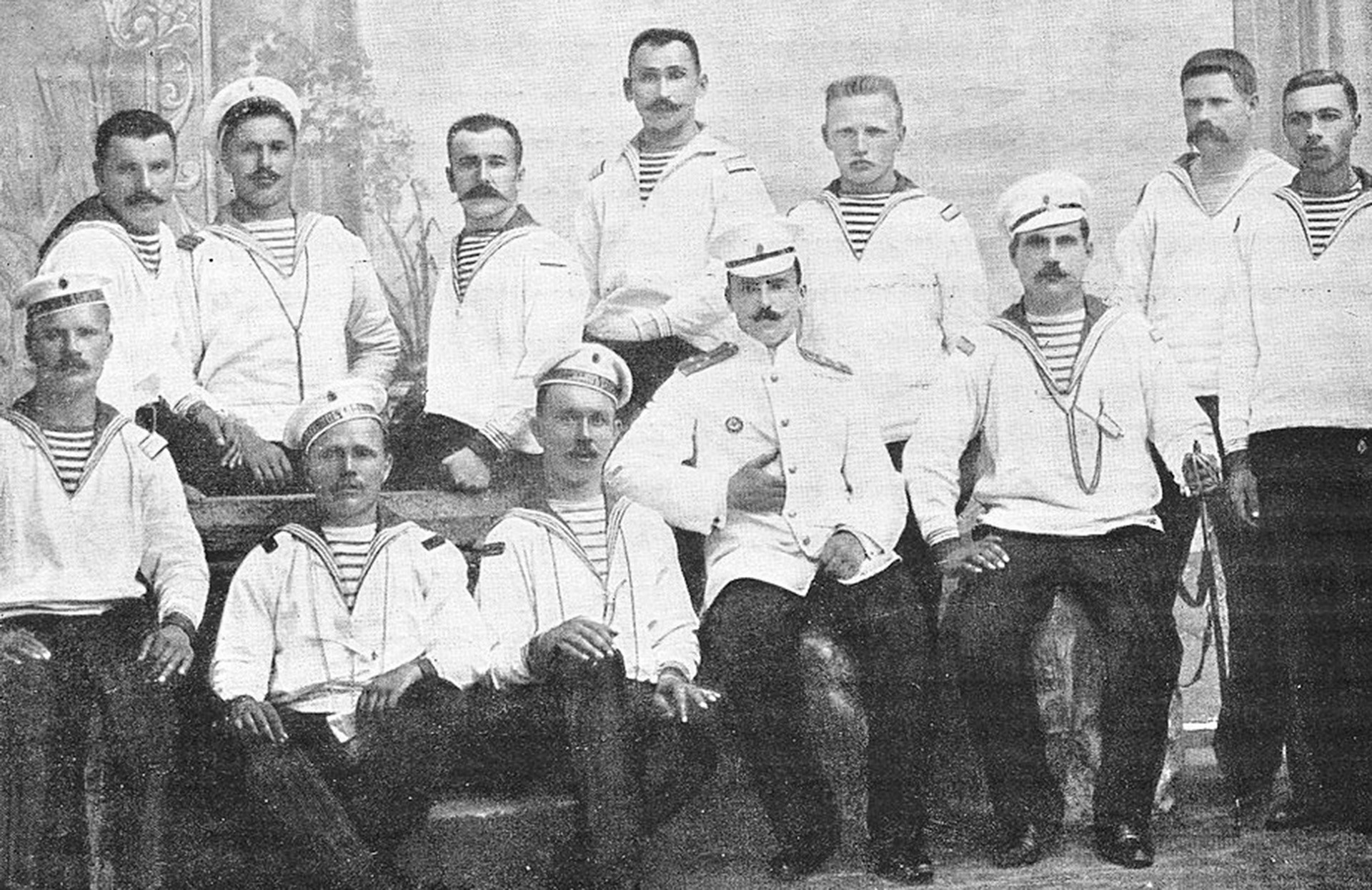

Some of the crew of the battleship Potemkin. The lieutenant in the center of the group was one of the officers killed by the rebels.

WikipediaThe revolutionary ship could not remain in Odessa, and since the revolutionary sailors did not want to expand their rebellion in the city, the Potemkin left for the Romanian port of Constanta, hoping also to take on food and fuel. The Romanians, however, refused to provide the ship with supplies, and so it set off for the Crimean port of Feodosia. There, however, it also couldn’t obtain the necessary supplies, and it returned to the Romanian port.

“Shameful story”

Meanwhile, the Black Sea Fleet sent a ship that was supposed to torpedo the Potemkin, but it couldn’t find the battleship that was sailing in the vicinity of Constanta. The main forces of the fleet were concentrated in their base at Sevastopol, where the situation was also on edge, and new mutinies were expected.

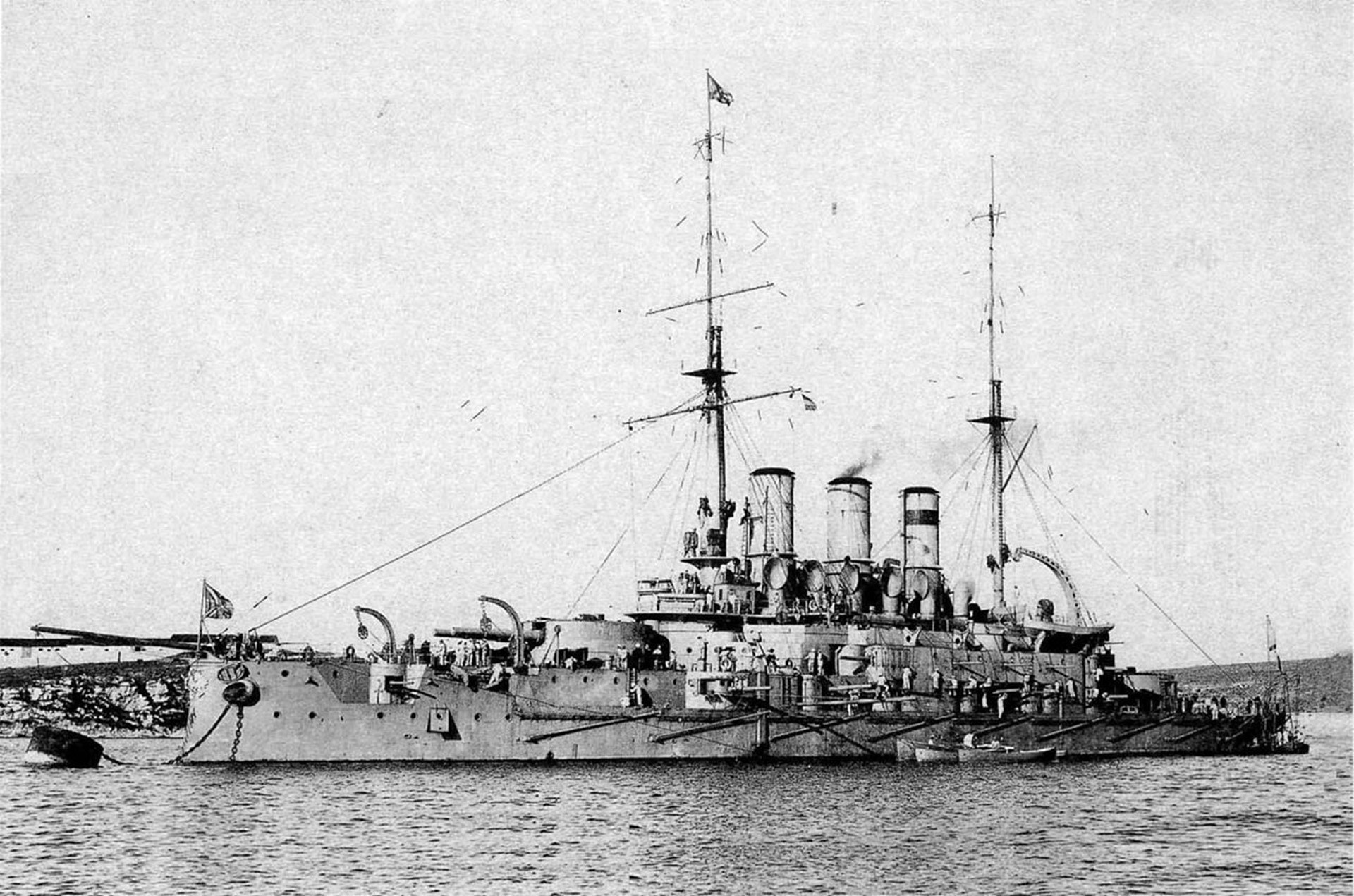

The battleship Potemkin at Constanta port in July 1905.

WikipediaThe story of the fleet being unable to capture the Potemkin and chasing it around the Black Sea was humiliating for Russia. “Let us hope for God’s sake that this difficult and shameful story is over,” Emperor Nicolas II wrote in his diary close to the end of the Potemkin’s adventures.

The Tsar’s indignation was intensified by Romania’s refusal to apprehend and extradite the Potemkin’s crew once the ship took up anchor there. Then, the sailors left the ship and obtained

Those sailors whom the Russian authorities eventually managed to capture were put on trial, and some were executed, and others were sent to harsh Siberian exile. Most of the mutineers, however, returned to Russia only after the Tsar was overthrown in February 1917.

Panteleimon in action

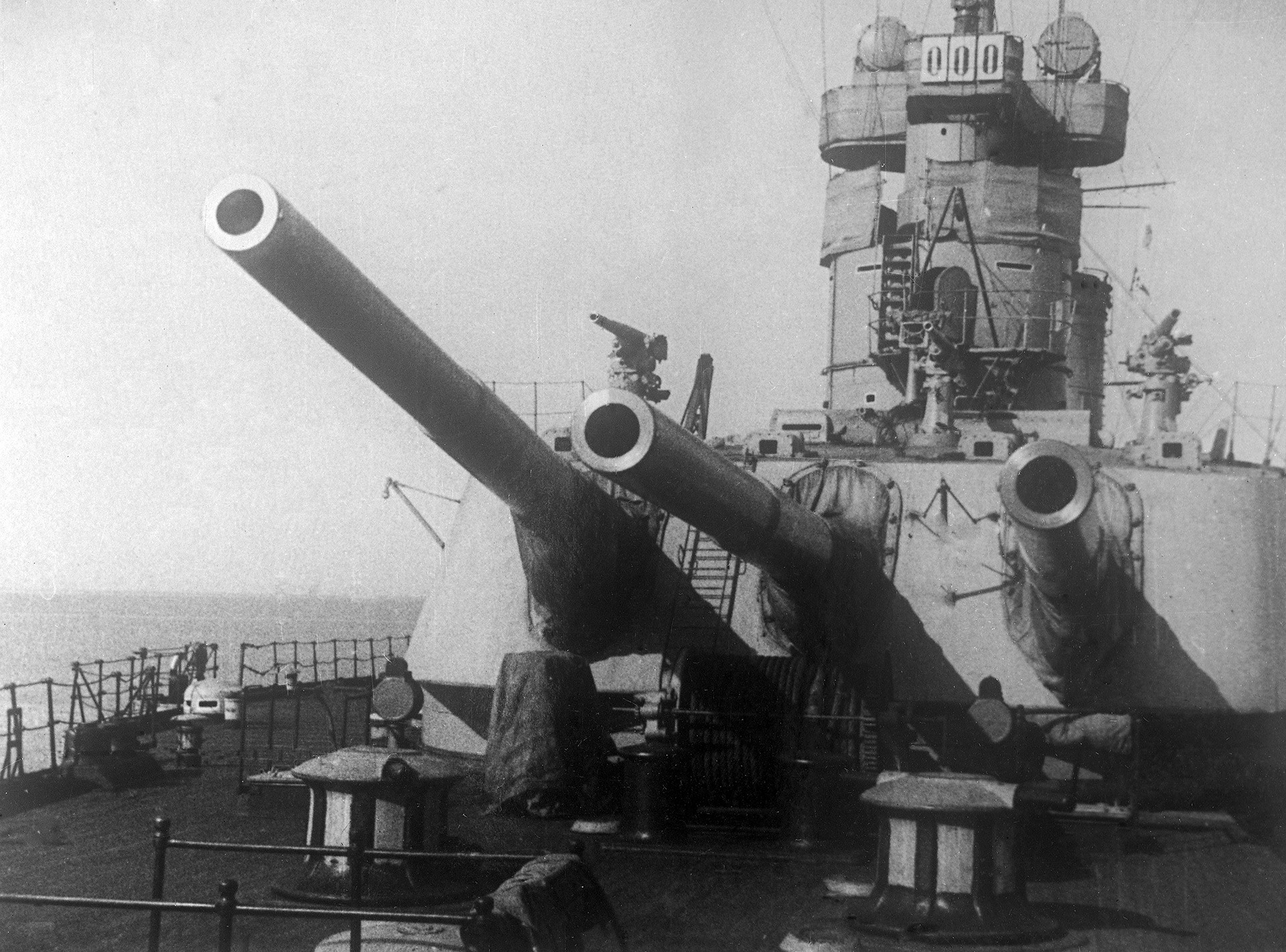

As for the Panteleimon, the ship subsequently saw limited action, as well as a number of mishaps. In 1909, it accidentally sank a Russian submarine. In 1914, just after the start of World War I, Panteleimon fought against the Ottoman Turkish navy at the Battle of Cape Sarych off the coast of Crimea, and a year later it engaged the Turks off their very own coast.

By 1916, the Panteleimon was demoted since it was almost obsolete, having been surpassed by new advances in naval technology. The ship was eventually captured by the Germans when they took Sevastopol in May 1918, and then after Germany’s

Imperial Russian battleship Panteleimon in Sevastopol, summer 1912.

WikipediaThe British destroyed her engines in 1919, however, in order to prevent them from coming in the hands of the advancing Bolsheviks. The death knell of the Potemkin/Panteleimon finally came in 1923 when the Soviets turned the useless and impotent ship into scrap metal.

In 1925, Eisenstein made his movie, giving the Potemkin legendary worldwide status as a symbol of Russia’s socialist revolution, even though the mutiny had taken place 12 years before the Bolsheviks had seized power.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox