Why did Napoleon invade Russia?

Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821), the French Emperor (1804-1814, 1815), had ambitions of total control over continental Europe, which meant not only political control over European states, which Napoleon achieved with his victorious military campaigns but also control over the seas and main trading seaports.

1. Napoleon wanted to ‘crush’ Russia

Emperor Napoleon I (1769-1821) by Jacques-Louis David, 1807

Emperor Napoleon I (1769-1821) by Jacques-Louis David, 1807

In 1807, Emperor Alexander I of Russia and Napoleon signed the Treaty of Tilsit, which ended the War of the Fourth Coalition (Russia, Prussia, Saxony, Sweden, and Great Britain against France) with France winning. According to the second Treaty of Tilsit, signed between France and Prussia, the Prussian king ceded almost half of his pre-war territories to Napoleon. On these territories, Napoleon created the Kingdom of Westphalia, the Duchy of Warsaw and the Free City of Danzig; the other ceded territories were awarded to existing French client states and to Russia.

A French medallion dating from the post-Tilsit period. It shows the French and Russian emperors embracing each other.

A French medallion dating from the post-Tilsit period. It shows the French and Russian emperors embracing each other.

The Treaty of Tilsit between Russia and France made the two great empires allies against Great Britain and Sweden. This created a harsh situation that very soon, in 1809, resulted in the War of the Fifth Coalition – a coalition of the Austrian Empire and the United Kingdom against Napoleon's France and its allied states. Prussia and Russia didn’t participate in this war, but it became apparent that Russia was the next country on Napoleon’s list. In 1811, Napoleon said to Dominique Dufour de Pradt, the French ambassador in Warsaw: “In five years, I shall be the master of the world, Russia alone remains; but I shall crush her... I shall then also be the master of the seas, and all commerce must, of course, pass through my hands.” The ‘friendship’ of the two emperors was shaky, to say the very least. “He’s a real Byzantine,” Napoleon said famously about Alexander, who was very elusive and didn’t like to be frank.

2. Russia didn’t join the continental blockade of the UK

The meeting of Napoleon I and Alexander I on the Niemen, 25 June 1807, by Adolphe Roehn

The meeting of Napoleon I and Alexander I on the Niemen, 25 June 1807, by Adolphe Roehn

According to the Treaty of Tilsit, Russia was to join the continental blockade against British sea trade: Britain was to be banned from exporting goods to continental Europe. And what did they export mainly at the time? Iron and textiles – the basic needs of any army that needs guns and uniforms. So with the blockade, Napoleon also wanted to deprive the armies of European countries, Russia included, of supplies. Also, because of the blockade, Russia’s export of grain, according to Russian historian Lubomir Beskrovnyi, decreased fourfold.

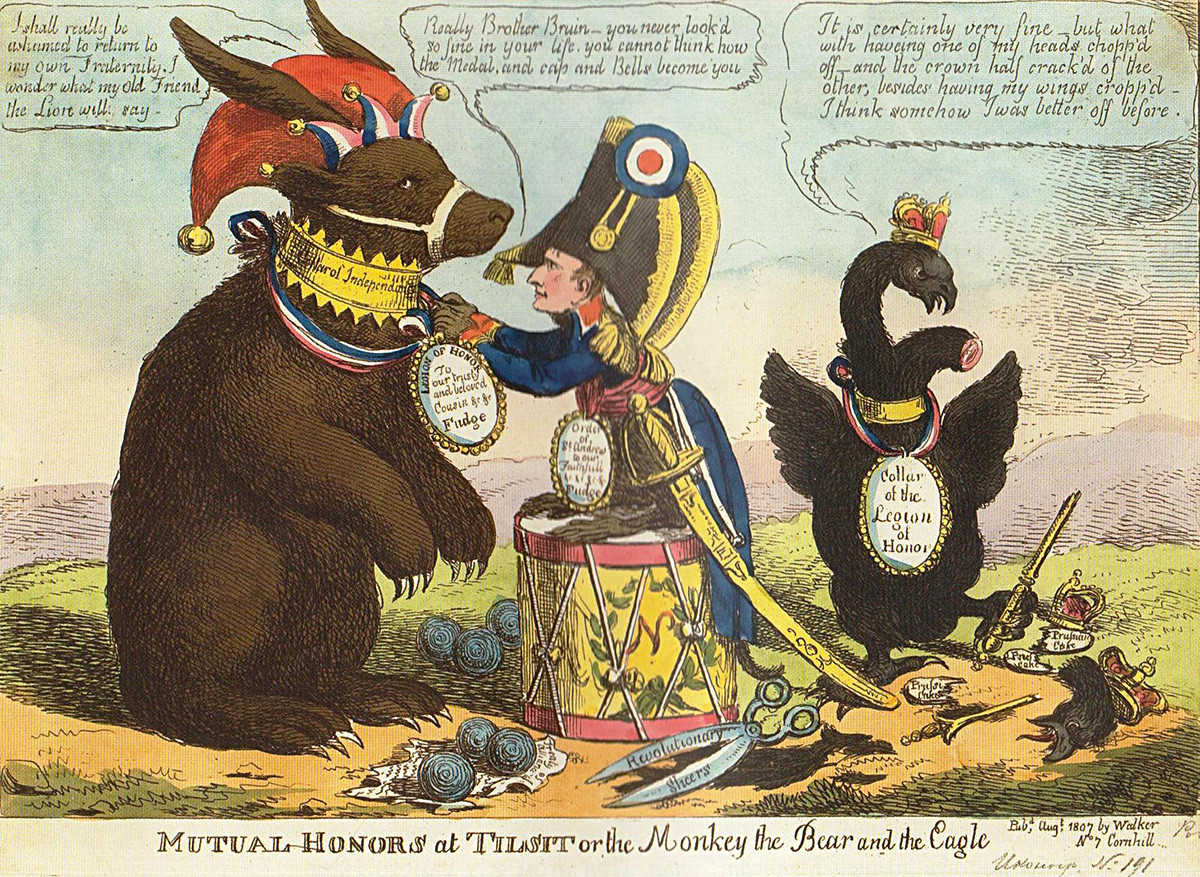

A satirical cartoon about the Treaty of Tilsit, by Charles Williams, 1807

A satirical cartoon about the Treaty of Tilsit, by Charles Williams, 1807

The blockade was clearly the opposite of what Russia as a political power wanted and needed – just like other European states. Napoleon’s direct orders to his navy to capture and restrain different nations’ trading ships that broke the blockade were often of no use. In 1810, Russia continued trade with Great Britain, and more, increased duties on French goods. This was an open offense.

3. Napoleon was insulted by two marriage refusals from Russian princesses

Catherine Pavlovna of Russia by Johann Friedrich August Tischbein

Catherine Pavlovna of Russia by Johann Friedrich August Tischbein

Napoleon didn’t have royal blood, and he wanted at least to marry into royalty. Twice he made marriage proposals to Russian princesses. By doing so, he also hoped to gain control over Russian politics through private influence. In 1808, shortly after the Treaty of Tilsit, French foreign minister Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand personally conveyed to Alexander I Napoleon’s proposal to Grand Duchess Catherine Pavlovna (1788-1819), Alexander’s sister. The proposal was turned down by Alexander – in his characteristic style of not saying anything specific.

Grand Duchess Anna Pavlovna of Russia, circa 1813.

Grand Duchess Anna Pavlovna of Russia, circa 1813.

In 1810, Napoleon proposed again, this time to 14 year-old Anna Pavlovna (1795-1865), later Queen of Netherlands, also Alexander’s sister. After this proposal was, too, turned down, Napoleon quickly married Marie Louise (1791-1847), daughter of Francis I (1768-1835), the Austrian Emperor. It was quite an obvious move: Napoleon needed this alliance with Austria if he wanted war with Russia, so his marriage exacerbated the relationship between two countries, already very damaged.

4. Russia allied with Sweden, which defected from Napoleon’s coalition

Jean Baptiste Bernadotte, Marshal of France, King of Sweden and Norway, 1818 after a painting by Francois Joseph Kinson

Jean Baptiste Bernadotte, Marshal of France, King of Sweden and Norway, 1818 after a painting by Francois Joseph Kinson

By then, Napoleon was assembling an international European allied army. Only one state refused to support the Great Army, and it was Sweden, headed by… Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte (1763-1844), a former Marshal of the French Empire turned Charles XIV John of Sweden through his wise political intrigues. With his wish to be an independent sovereign, Bernadotte (Charles XIV John) didn’t fit into Napoleon’s system, and they became enemies.

In January 1812, Napoleon occupied Swedish Pomerania. In March, Bernadotte chose to ally Sweden with Russia. Alexander promised Bernadotte help in also becoming the King of Norway (which later actually happened).

Napoleon's army crossing the Neman in 1812

Napoleon's army crossing the Neman in 1812

The alliance with Sweden was decisive for Russia. Shortly after, on May 28th 1812, Russia signed the Treaty of Bucharest with the Ottoman Empire, which ended a six year war. The Ottomans have also pledged to withdraw from their alliance with France. The treaty, signed by the Russian commander Mikhail Kutuzov, was ratified by Alexander I of Russia 13 days before Napoleon's invasion of Russia.