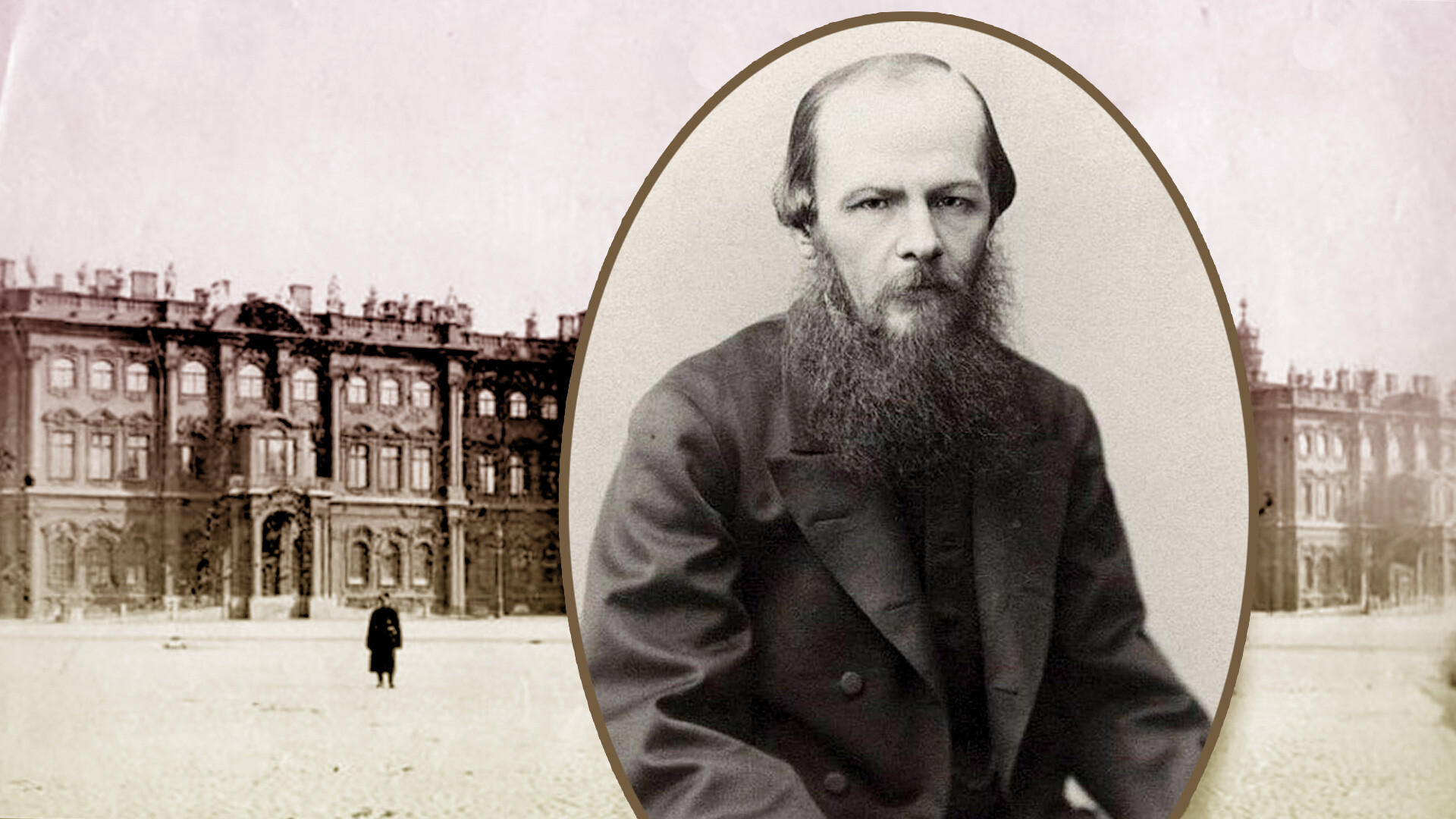

Fyodor Dostoevsky was born and raised in Moscow, but in later life he lived almost 30 year in St Petersburg. Having no home of his own, he rented apartments and changed address several times.

Anichkov Bridge.

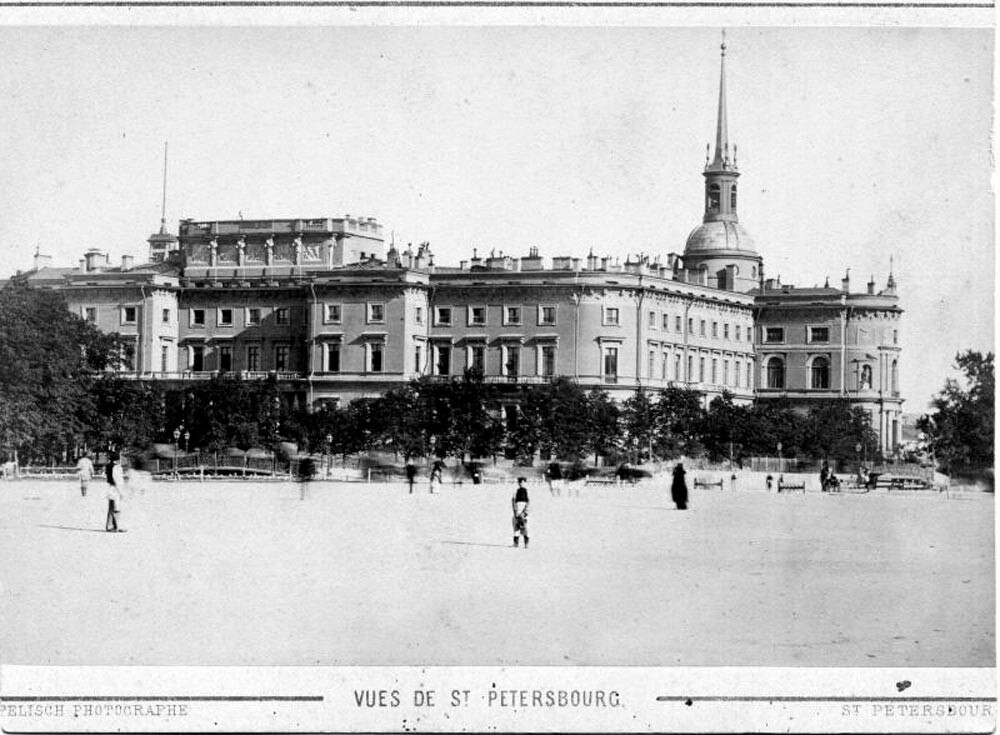

Alfred Eberling/V.A. Nikitin collection/russiainphoto.ruHis father sent the teenage Fyodor to study at the Military Engineering Institute, which was located inside Mikhailovsky Castle, the palace of the late Emperor Paul I, in St Petersburg (pictured). A fellow student of the future writer, Dmitry Grigorovich, recalled that the young Fyodor was uncommunicative and did not take part in social games, but rather "sat deep in a book, away from everyone."

Mikhailovsky Castle (Military Engineering Institute)

Albert Felish/MAMM/MDF/russiainphoto.ruA stone’s throw from the institution were the Summer Garden and the chain-type Panteleymonovsky Bridge across the Fontanka River. This was replaced in the early 20th century by a road bridge for cars.

Fontanka River near the Summer Garden

Karl Bulla/MAMM/MDF/russiainphoto.ruIn 1849, Dostoevsky was arrested and spent eight months in prison at the Peter and Paul Fortress. The initial death sentence was commuted quite literally at the last minute to hard labor in Siberia. Dostoevsky was accused of being a member of a revolutionary circle and of disseminating a banned letter from literary critic Vissarion Belinsky to writer Nikolay Gogol in 1847, which called for civil liberties and the abolition of serfdom.

Peter and Paul Fortress

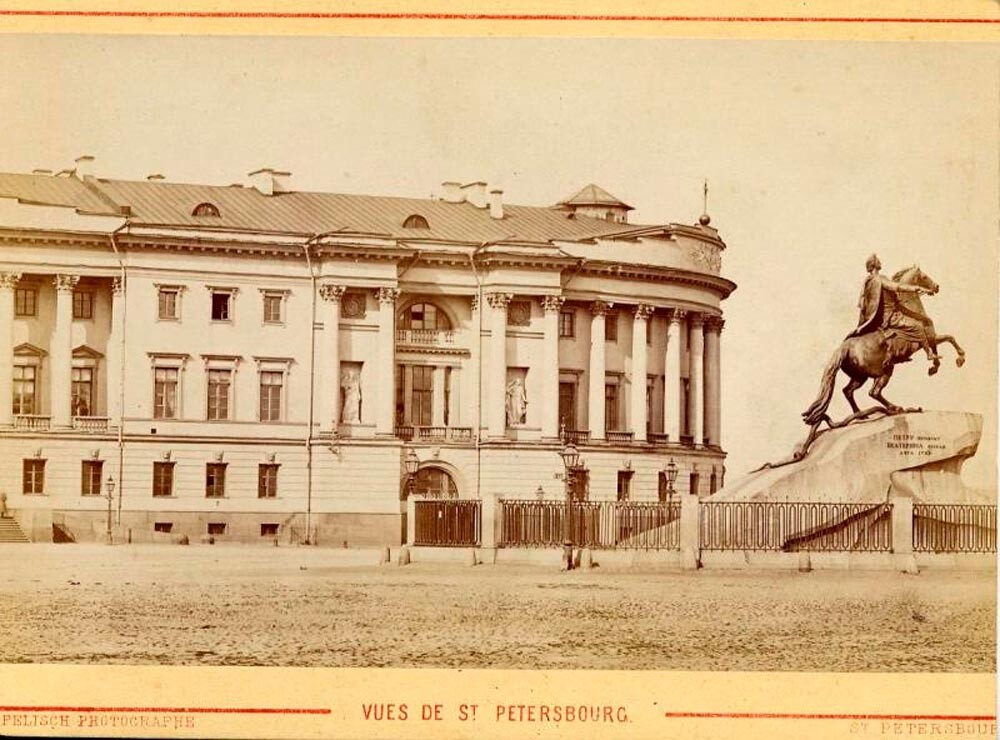

Karl Bulla/MAMM/MDF/russiainphoto.ruThe first literary diatribe against the famous monument to Peter the Great, the city’s iron-willed founder, came from the protagonist of Pushkin's poem The Bronze Horseman. After a terrible flood, he curses Peter for having founded his new capital in the middle of a swamp with a dreadful climate. In the novel A Raw Youth, Dostoevsky voices a similar sentiment: "What if this fog should part and float away, would not all this rotten and slimy town go with it, rise up with the fog and vanish like smoke, and the old Finnish marsh be left as before, and in the midst of it, perhaps, to complete the picture, a bronze horseman on a panting, overdriven steed?”

'The Bronze Horseman' monument

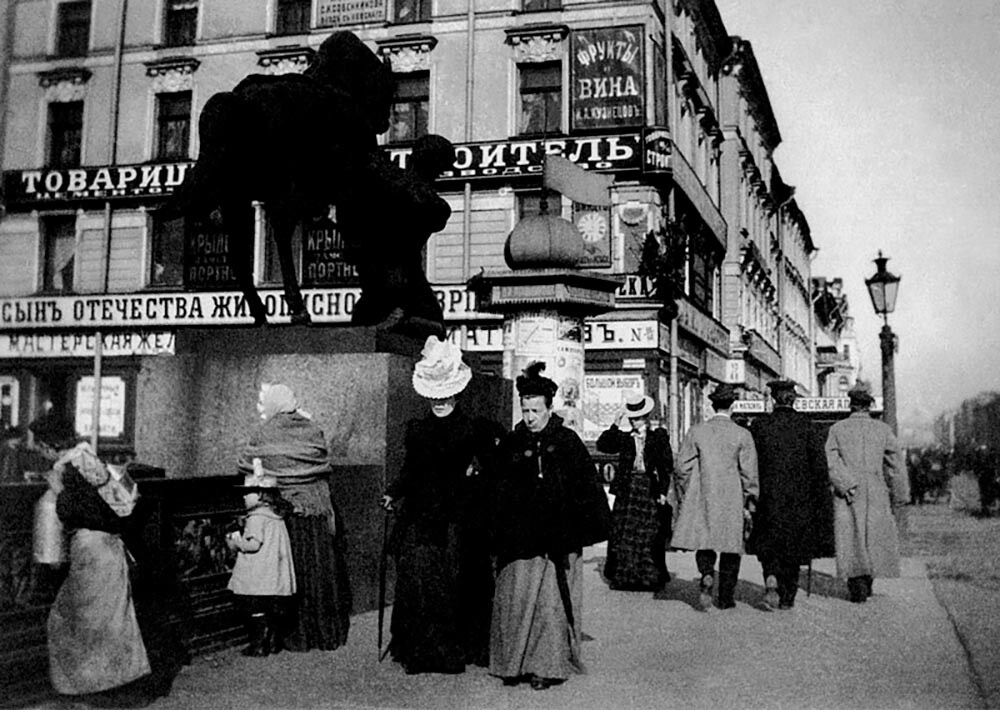

Albert Felish/MAMM/MDF/russiainphoto.ruAlthough Dostoevsky’s novels paint a gloomy, rather than grand, St Petersburg, the writer himself often went to Nevsky Proskpekt, the city’s “shop front”, where bankers and merchants worked and elegant ladies strolled. And when the writer lived abroad and did not have a rented apartment, he stayed in a hotel on Nevsky Prospekt when visiting.

Nevsky Prospekt

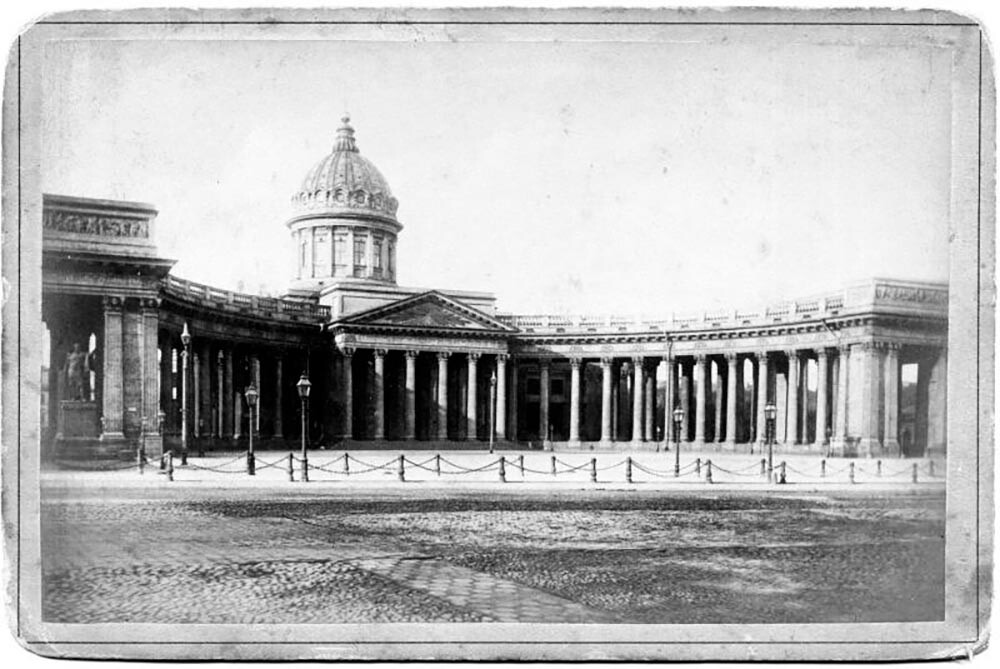

Ivan Nostitz/MAMM/MDF/russiainphoto.ruThe writer used to go to Kazan Cathedral on Nevsky Prospeckt to pray (his wife stated that he went there after the declaration of the Russo-Turkish War in 1877, for example).

Kazan Cathedral

MAMM/MDF/russiainphoto.ruA minute's walk from Kazan Cathedral was (and still is) the famous Wolf & Beranger candy store, where Dostoevsky loved to visit and where, in 1846, he made the acquaintance of Mikhail Petrashevsky, the organizer of the above-mentioned secret revolutionary circle. It was at a meeting of the circle that Dostoevsky read Belinsky’s banned letter. Petrashevsky, also exiled to Siberia, was later immortalized as the impish Petr Verkhovensky in the novel Demons.

Kotomin House on the corner of Nevsky Prospekt and Bolshaya Morskaya street

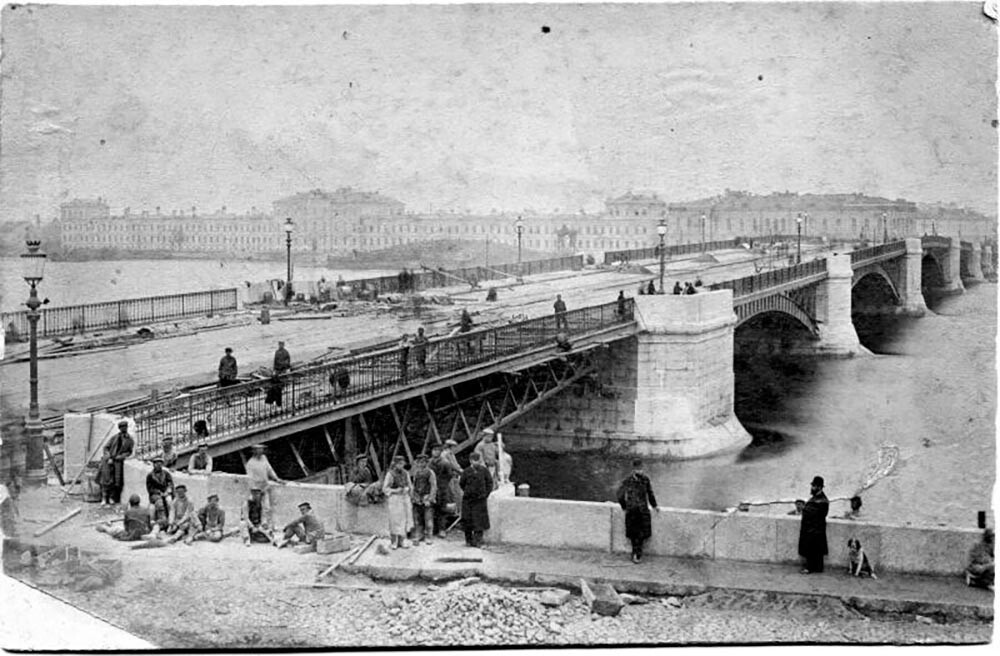

Public domainMany places in St Petersburg are described in Crime and Punishment. On Nikolaevsky (now Blagoveshchensky) Bridge, the novel’s antihero Rodion Raskolnikov, lost in thought, is nearly run over by a horse-drawn carriage, and gets whipped on the back by the livid driver. A couple of compassionate young ladies take him for a beggar and give him alms.

Nikolaevsky Bridge with horse-drawn railroad

Karl Bulla/MAMM/MDF/russiainphoto.ruRaskolnikov also wandered past the Summer Garden, wishing that the whole city could be immersed in such greenery with fountains everywhere to refresh the dusty city air: “Then he was interested by the question of why in all great towns men are not simply driven by necessity, but in some peculiar way inclined to live in those parts of the town where there are no gardens nor fountains; where there is most dirt and smell and all sorts of nastiness.”

St Alexander Nevsky Chapel in the Fence of the Summer Garden

Public domainAnd here is the embankment of the Catherine Canal near St Nicholas Naval Cathedral. Not far from there lived the old pawnbroker who was murdered by Raskolnikov, and further along the canal lived his beloved Sonya Marmeladova. Today, the waterway is called the Griboyedov Canal, and Dostoevsky did not live to see the construction of its main attraction: the Church of the Savior on Spilled Blood. Just one month after the writer’s death, Emperor Alexander II was assassinated on the site of the present-day church, which stands as a memorial to the late tsar. Had he been alive, Dostoevsky would have been shocked to the core by this event: he was a patriot and a monarchist, who was deeply concerned about the growing number of attempts on the tsar's life.

St Nicholas Naval Cathedral

Archive of A.N. Odinokov/russiainphoto.ruRaskolnikov himself lived not far from Sennaya Square, an artisan district. “Near the taverns on the lower floors, in the dirty and smelly courtyards of the houses of Sennaya Square, and most of all near the drinking houses, there crowded all sorts of craftsmen and rag merchants.”

Sennaya Square (a later photo of 1900)

Public domainThis street fishmonger could have been lifted from pages of a Dostoevsky novel. “Again the stench from the shops and the drinking houses, again the drunken men, the Finnish pedlars and half-broken-down cabs.”

Fishmonger

Karl Bulla/MAMM/MDF/russiainphoto.ruIn Crime and Punishment and other works, Vasilyevsky Island plays a major role; the writer himself lived there at several addresses. Not having money for a cab, the protagonist of The Humiliated and the Insulted goes there on foot, even though it lies at the other end of the city. Once Dostoevsky almost fell ill while was walking "to Vasilyevsky [where he and his wife lived at that time], it was a long way to go.” Just as people today use carsharing services, so too in Dostoevsky’s time travelers going in the same direction would split the cost of a cab — or use their own vehicle as a taxi: “...on hearing that I was going to Vasilyevsky, he kindly offered me a ride.”

Coachman on the spit of Vasilyevsky Island

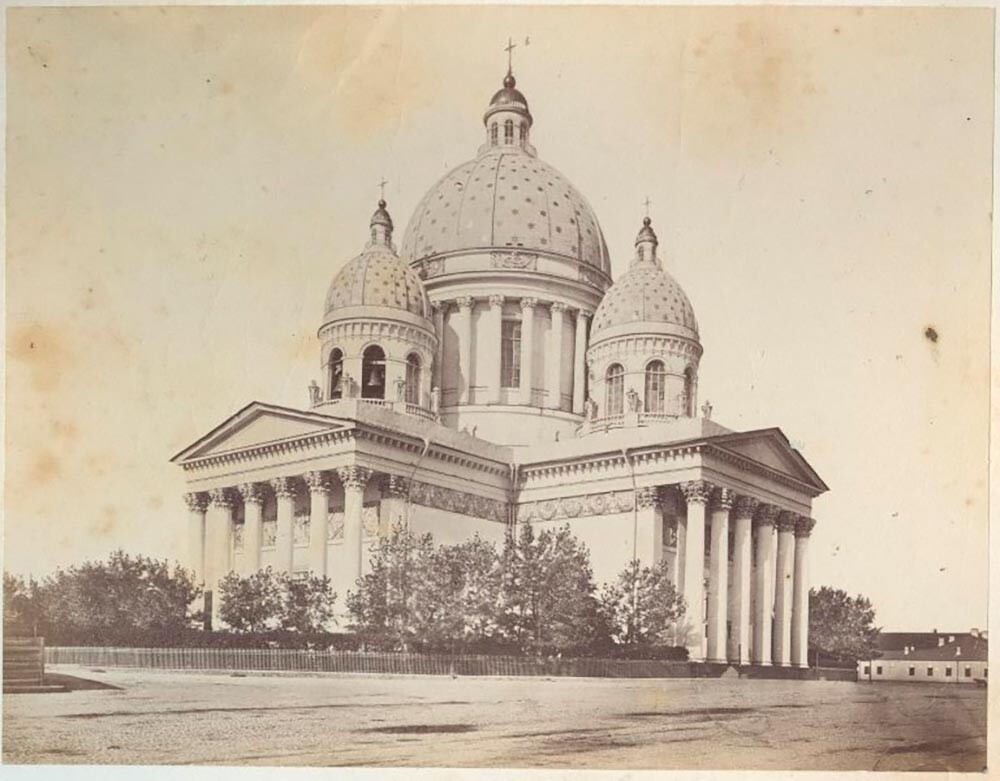

Karl Bulla/MAMM/MDF/russiainphoto.ruOf special significance for the writer was Trinity Cathedral. It was here in 1887 that he married his second wife Anna Snitkina, who was 25 years his junior. She was his stenographer, and without her help The Idiot, Demons, A Raw Youth, The Brothers Karamazov and other works probably would not have seen the light of day.

Trinity Cathedral

Alfred Lawrence/MAMM/MDF/russiainphoto.ruThe building of the Kurt Siegel Mechanical Plant was constructed in 1876 on Yamskaya Street in St Petersburg. Now it bears the name Dostoevsky Street. On the corner of this street stands the house in which his last apartment was located, where he lived from 1878 until his death in 1881. Today it houses a memorial museum dedicated to the writer.

The Kurt Siegel Mechanical Plant

MAMM/MDF/russiainphoto.ruDostoevsky lived to see the construction and opening in 1879 of the drawbridge-type Alexandrovsky (now Liteiny) Bridge, one of the city's calling cards. Just as people say that Moscow is not Russia, so Dostoevsky believed that St Petersburg was not representative of the country as a whole. “After all, you cannot deny that they did not know the soil, knew Russia through service in St Petersburg, had a baron-serf relationship with the people,” he wrote in his Diary of a Writer about the heroes of Pushkin and Gogol.

Alexandrovsky (now Liteiny) Bridge under construction

MAMM/MDF/russiainphoto.ruIf using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox