At the wedding of Anna, Peter the Great’s daughter, and Charles Frederick, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp, in 1725, the guests were entertained by dwarves.

“From the pâté placed on the bride’s table,” a German nobleman Friedrich Berchholz describes the wedding, “a very small and handsome dwarf dressed as a footman jumped out with unusual agility, holding a bottle and a glass to drink to the health of the royal bride. And, from the other pâté, which stood on the table the bridegroom, at the same time came, a pretty female dwarf dressed as a shepherdess, who, after a deep curtsy to His Highness and after a bow to all the society, danced around the pâté.”

But where, in the European power that was Russia in 1725, did such entertainment come from? It was started by the first emperor himself, because he, too, had room dwarfs in his childhood. In pre-Petrine times, the court of the Moscow tsars also had various jesters and freaks and they often had to endure humiliation worse than popping out of a cake.

"Ivan the Terrible demonstrates his treasures to Jerome Horsey, ambassador of Queen Elizabeth I of England," 1875. In the left lower corner, one of Ivan's jesters is pictured.

Alexander Litovchenko/Russian MuseumCourt jesters appeared in Russia under Ivan the Terrible. It is possible that the first Russian tsar tried to imitate Henry VIII (1491-1547), at whose court lived the jesters Will (Sommers) and Jane Foole, even depicted together with the monarch in his ceremonial portrait. Sommers was an iconic figure at court: he could address the king directly and jokingly warned him against unreasonable spending and drastic actions. Later, he even attended the coronation of Elizabeth I of England. In the Moscow Tsardom, jesters never played such a role – it belonged to “holy fools”.

Basil the Blessed could call the tsar by his diminutive name ‘Ivashka’ and the tsar, in response, did not order the execution of the holy fool. It was believed that God spoke through the mouths of the blessed. Jesters, on the other hand, were quite secular, with their own lives outside the jester “profession”. Even a Rurikovich prince, relegated to a disgraceful position for political purposes, could have been a jester under Ivan the Terrible.

"Henry the Eighth and His Family," by unknown artist, c. 1545. The man at the far right is the jester Will Somers, and it has been suggested that the woman at the far left is the jester Jane Foole.

Legion MediaPrince Iosif Gvozdev-Rostovsky, at first, served in the tsar’s army, but then he became a jester and was called ‘Osip Gvozd’ ('Osip the Nail'). Historian Nikolay Karamzin reports that, “dissatisfied with some joke, the Tsar poured a bowl of hot soup over him. The poor jester yelled and wanted to flee: Ivan then stabbed him with his knife.” The English doctor who was summoned only stated Gvozdev’s death, to which “the Tsar shook his head, called the dead jester a disgraceful dog and went on having fun. In this case, Tsar Ivan committed, of course, a political murder – we know that he eliminated many princes and boyars who disagreed with his policies. He was known to cut off the ear of another boyar once; he once stabbed another courtier in the foot with the sharp point of his staff. Neither a fool nor an ordinary jester was usually treated in this way.

At Ivan the Terrible’s court, the tsar and his guests were entertained by the skomorokhs, artists from pagan times, whom the Orthodox Church could not tolerate. They wore funny dresses and masks, staged comic sketches, trained bears, played cymbals, tambourines, domras, reeds and gusli (Russian plucked zithers). As Samuel Collins, the physician to Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich, wrote: “Take a few owls, a few starlings, a couple of hungry wolves, seven pigs, as many cats with their spouses and make them all sing.” That, to the European ear, was how the skomorokh instruments sounded.

Engraving of Will Sommers by Francis Delaram, c. 1615–1624.

Public domainHowever, in the 17th century, only the music remained of the skomorokhs: the first Romanovs were pious kings and did not allow dances and masks in their palaces. Only musicians remained at court: “The gusli players, domra players and fiddlers” played during Mikhail Fyodorovich’s reign during feasts in the palace, “all day long and into the evening”. Under Tsars Mikhail and Alexei, European musicians, such as organists, also appeared in the male quarters of the royal palaces, where foreign guests were often received. But dwarfs and freaks continued to live in the depths of royal palaces throughout the 17th century.

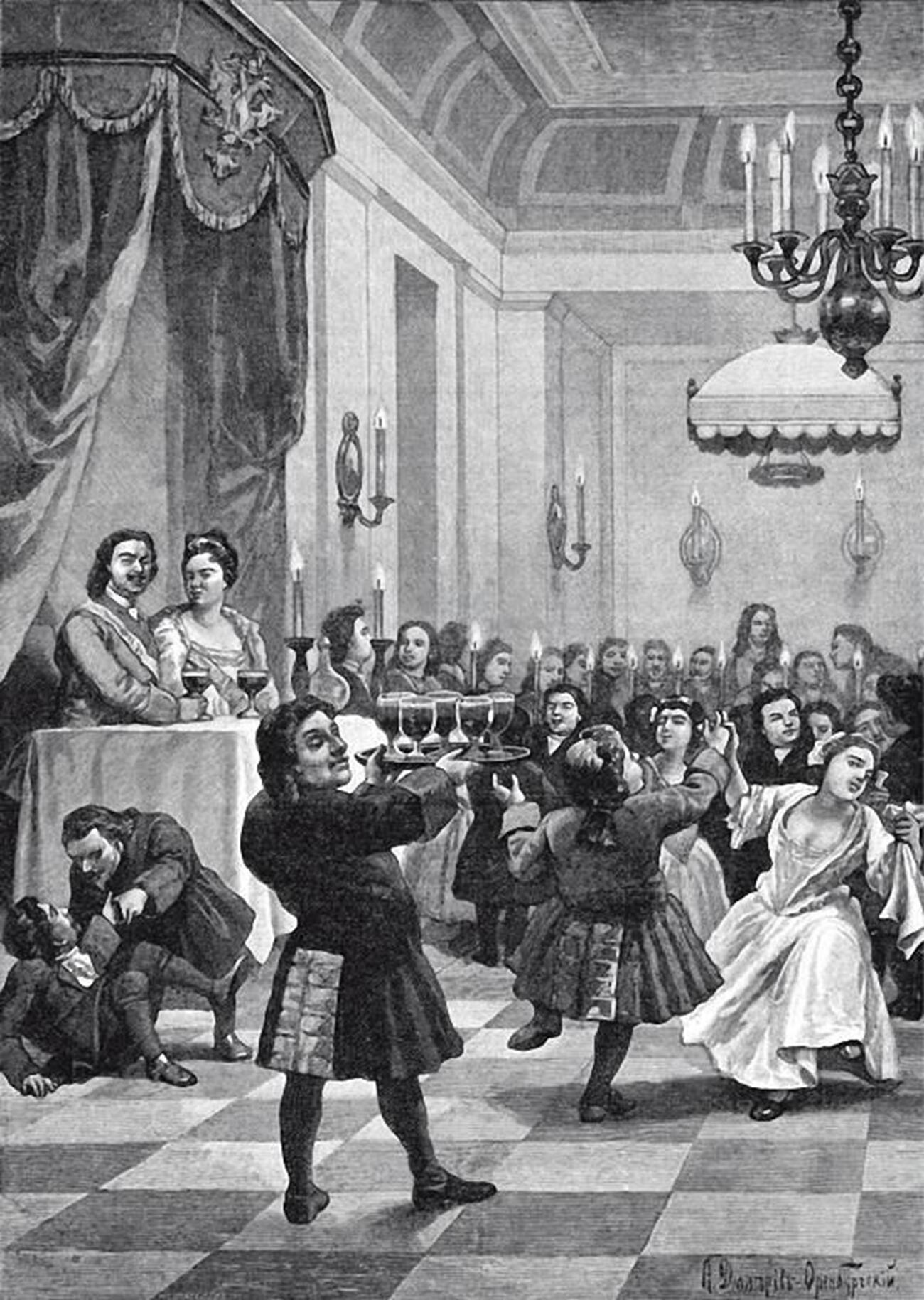

"The dwarfs' wedding under Peter the Great," by Nikolay Dmitriev-Orenburgsky. Peter the Great and his wife, Catherine, can be seen on the left.

Nikolay Dmitriev-OrenburgskyEven in Peter’s Russia, dwarfs continued to live with the Russian nobility and the tsars. ‘The list of dwarfs that are in Moscow’, compiled in 1710, shows that two dwarfs belonged to Tsarina Praskovia Feodorovna (wife of Ivan Alexeevich, Peter’s half-brother) and Tsarina Marfa Matveyevna (wife of the late tsar Feodor Alexeevich). Also dwarfs lived in the homes of the boyars Shein, Saltykov, Prozorovsky, Khovansky, Apraksin, Naryshkin – all of these families belonged to the old Moscow nobility. In total, in Moscow in 1710 there were 34 domestic dwarfs.

Dwarfs also accompanied the little Tsarevich (prince) Peter, who in the first years of his life was brought up in the old Moscow traditions. The dwarves were the first “retinue” of the little tsarevich. When he grew up, dwarves and midgets became the first soldiers of his army, from which the famous Izmailovsky and Preobrazhensky regiments later emerged. Even in the quite serious Kozhukhov maneuvers in 1694, a pack of 25 dwarfs, dressed in tiny colorful uniforms, took part.

When Peter turned nine, his older brother tsar Fyodor Alexeyevich gave him the jester Komar (‘Mosquito’, born Yakim Volkov), who later, according to legend, saved the tsar during the riot of the Moscow streltsy (royal guard) in 1682. In November 1710, tsar Peter arranged a dwarf wedding – Komar was married to the female dwarf of Tsarina Praskovia Fyodorovna. Shortly before the wedding, Peter issued a special decree: “Dwarves, male and female… should be sought for all across Russia and sent to St. Petersburg.” He also ordered to make appropriate dresses for all these dwarves: “Kaftans (robes) and camisoles of fine, colored cloth, with gold-braided trims and buttons, and swords and hats; and German stockings and shoes; for the female sex – black dress and underwear and fancypants and any decent-looking good attire.” This was how the Tsar gathered his guests for a “miniature” wedding.

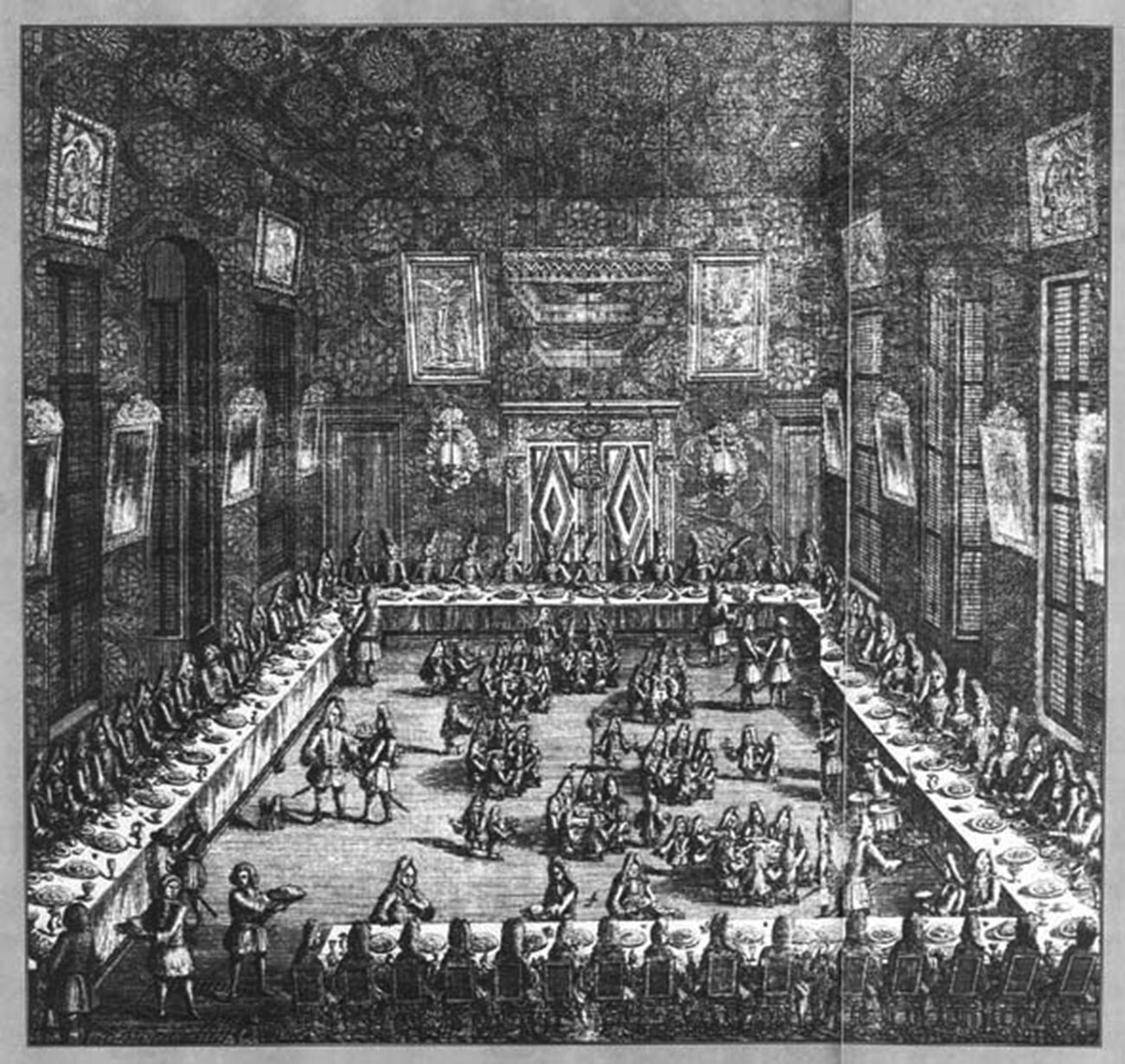

"The dwarfs' wedding under Peter the Great," an etching by Alexey Zubov, 1711.

Alexey Zubov/Pushkin State Museum of Fine ArtsOn the wedding day, the couple was married in accordance with the Orthodox rite. The tsar himself, several ministers and boyars – and a fancy procession of 72 dwarfs and midgets, all dressed up, took part in the solemn procession to the church. When they arrived home to celebrate, “the dwarfs, dapper and richly dressed in European attire”, occupied several small tables in the middle of the hall, while Peter and his guests sat by the walls to see everything clearly – the feast, the dancing of the dwarves and then the dwarf fight (possibly pre-arranged, as most of the dwarves had acting experience). However savage it may seem now, to Peter’s guests, including the Danish envoy Just Juel, who described it, there was nothing unusual about what was going on: “What jumps, wriggles and grimaces there were, it is impossible to imagine! – the Danish envoy wrote excitedly. “All the guests, especially the tsar, could not amuse themselves enough and, looking at the mangling and grimacing of these 72 ugly men and women, almost rolled on the floor laughing.”

This was not the only jester wedding arranged by Peter. In 1695, he held the wedding of one of his jesters, Yakov Turgenev. The wedding was attended by real boyars and other high-ranking officials. They rode “on bulls, on goats, on pigs and on dogs and wore ridiculous dresses, in piles of whiskers, in bald caps, in dyed coats, covered with cat’s paws and squirrel tails, in straw boots, with mouse gloves, in straw hats”.

It is evident from these outfits that the chief wedding planner, tsar Peter, had an excellent understanding of Russian laughter culture and borrowed much from the pagan rituals of Svyatki, the old Russian pagan feast. Svyatki is an old Russian pagan rite of passage, a passage from one year to another, which was celebrated after the winter solstice. The Svyatki games, therefore, traditionally parodied the rites of passage, such as weddings – and funerals. Tsar Peter also was known to hold a dwarf funeral.

"Jesters at the court of Anna Ioannovna," by Valeriy Yakobi, 1872.

Valeriy Yakobi/Tretyakov GalleryOn February 1, 1724, the funeral of the jester Komar (Volkov) took place – 14 years after his famous wedding. The funeral service was performed by “a tiny priest, who was deliberately chosen for this procession because of his small stature”. The deceased was carried in a small coffin placed on a small sleigh pulled by ponies and led by the court pages, young boys from noble families. In the funeral procession were rows of dwarfs and dwarves, led by dwarf “marshals” with large wands in their hands, taller than the “marshals” themselves. In stark contrast, on both sides of the procession “about 50 huge guardsmen walked with burning torches in their hands”. The tsar himself also took part in the procession, along with Prince Menshikov, but they were not in mourning attire – because Peter, again, apparently entertained himself: for example, he personally threw the dwarfs into the huge sleigh in which they were to be taken to the wake feast.

This was the last amusing ceremony in which Peter participated. After his death, under subsequent rulers and, especially under Anna Ioannovna, who was also brought up in Moscow traditions, dwarfs and jesters were still present at court. It was under Anna Ioannovna that the wedding of the jester Golitsyn and the jester Buzheninova took place, during which the newlyweds had to spend the night in an ice palace. After Anna’s reign, jesters in the Russian Empire became a relic of the past.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox