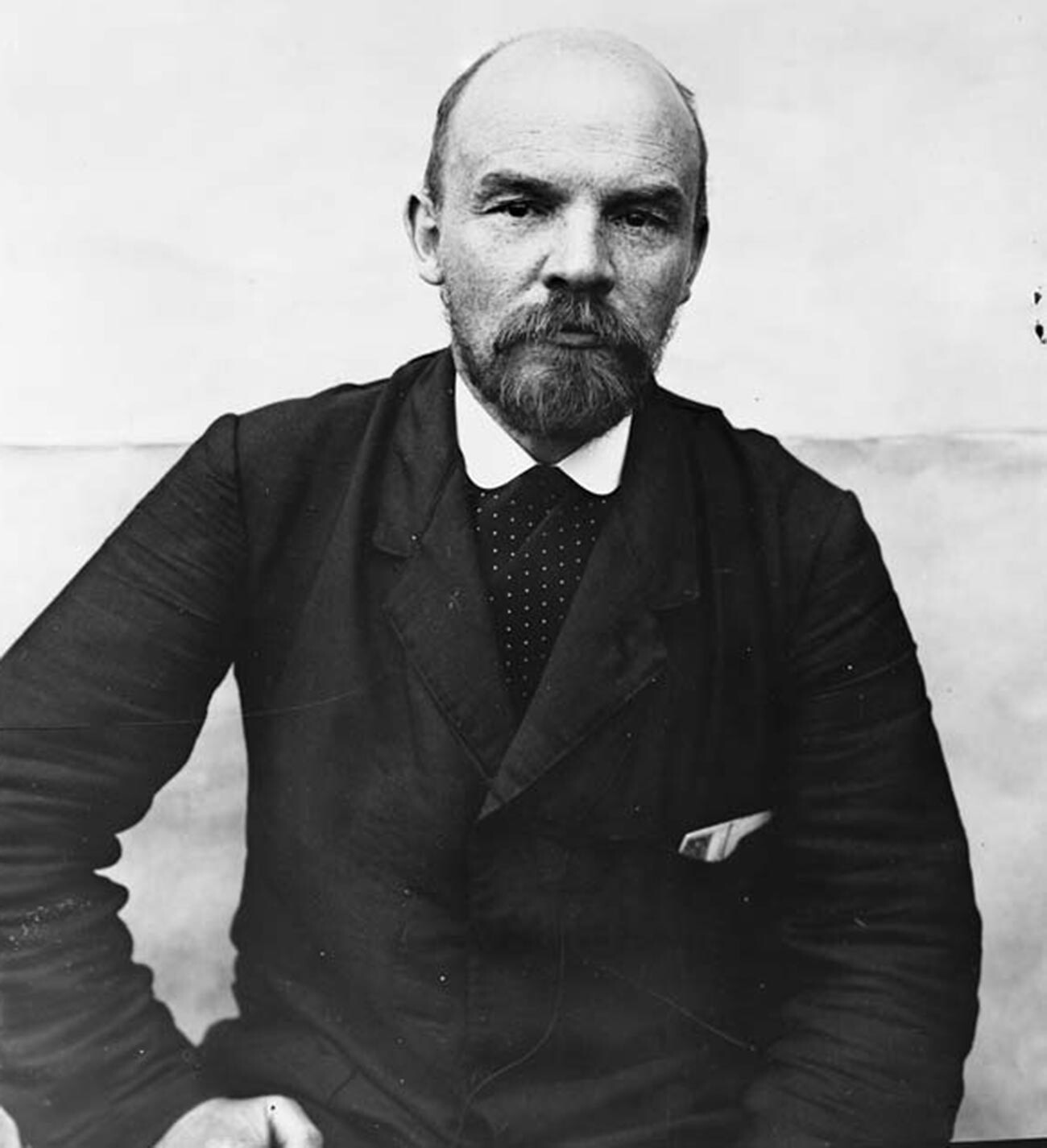

The most famous nobleman who trod the path of revolutionary struggle and eventually led the world’s first “socialist state of workers and peasants” was Vladimir Lenin (born Vladimir Ulyanov). His father, Ilya Ulyanov, in 1877 was conferred with the rank of state councilor in deed, which granted hereditary nobility to himself, his wife and his children.

Lenin also had noble blood through his maternal lineage. In the 1840s, his grandfather, Alexander Blank, rose to the rank of court councilor and, having received the right to hereditary nobility, acquired the Kokushkino estate in Kazan Province.

“I also lived in the manor house that belonged to my grandfather,” Vladimir Ilyich admitted to his colleague Mikhail Olminsky: “In a way, I too am a landowner’s son. Many years have passed since then, but I still have not forgotten the pleasant aspects of life at the estate, its lindens and flowers. Execute me. I remember with pleasure how I used to lie on mowed hay I had not cut, ate strawberries and raspberries I had not planted, drank fresh milk from cows I had not milked.”

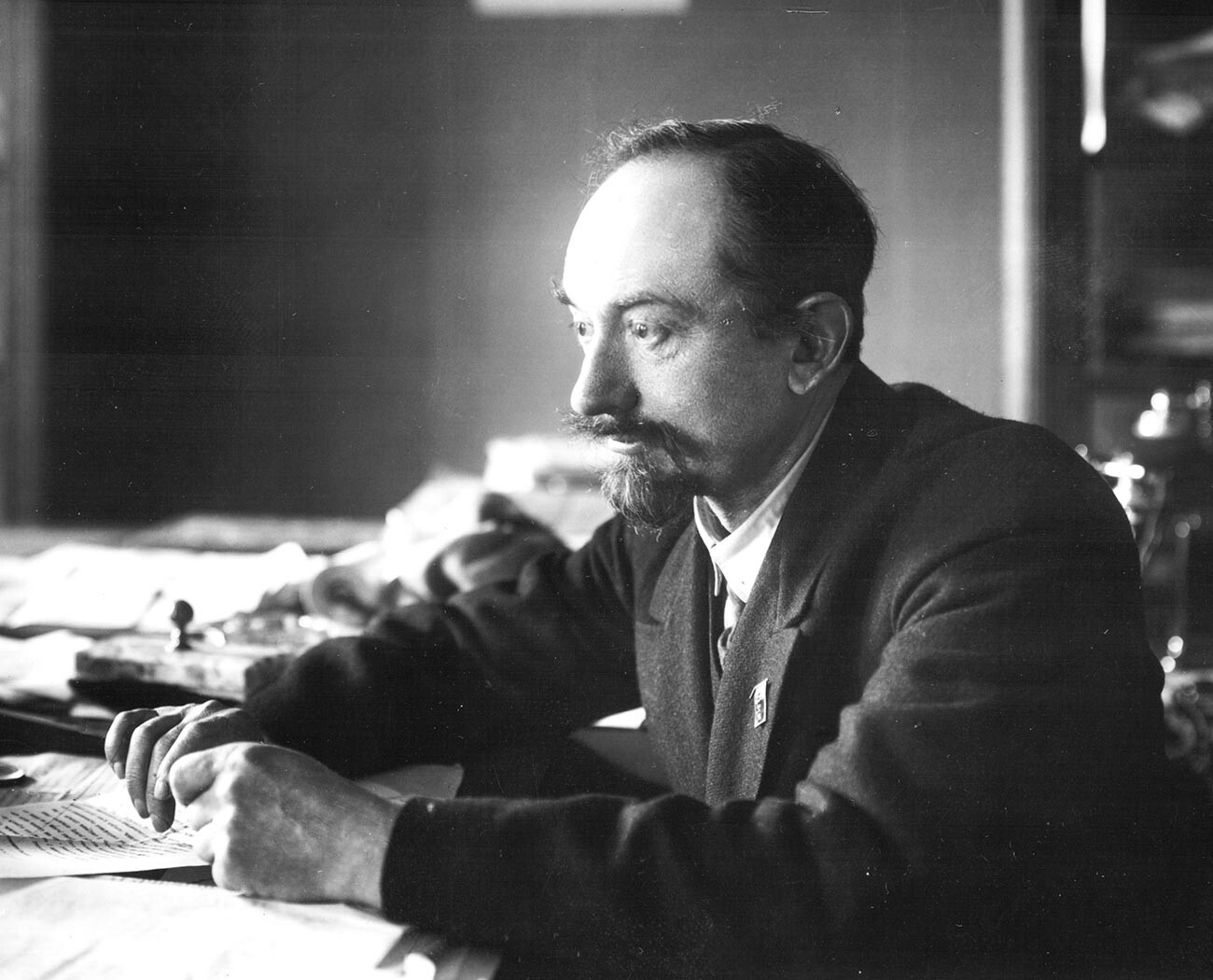

Few Bolsheviks could boast a pedigree like Georgy Chicherin. This prominent Soviet diplomat descended from the ancient Russian noble Chicherin family on his father’s side, and from the Ostsee (Baltic) baronial Meyendorff family on his mother’s. Nevertheless, Georgy chose the socialist struggle.

For 12 years, the hereditary diplomat Chicherin headed the country’s foreign affairs department, holding the post of People’s Commissar (Minister) of Foreign Affairs, first of the RSFSR, then, from 1923, of the USSR. With his direct involvement, the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was concluded with Germany on March 3, 1918, whereupon Russia withdrew from WWI. In addition, he played a key role in bringing the country out of the international isolation it found itself in after the Bolsheviks came to power.

“Chicherin is a marvelous worker, conscientious, intelligent, knowledgeable,” Lenin said of him. “Such people should be valued. His weakness, namely a lack of ‘commandship’ is not a problem. Show me someone who doesn’t have a weak side!”

A member of the Soviet government and one of Stalin’s chief economic advisers, Valerian Kuibyshev, was born in Omsk in the noble family of Lieutenant Colonel Vladimir Kuibyshev and his wife, school teacher Yulia Gladysheva. Despite its noble origins, the family could barely make ends meet.

“Not only was the family not wealthy, but lived below the average income,” recalled Elena, Valerian’s sister. “Father and Mother’s earnings were only enough to live and raise the family’s eight children. Clothes and shoes were always handed down from the elder children to the younger. Everything was thoroughly restitched and redone several times.”

Kuibyshev oversaw the development of the Soviet economy and led the drive toward electrification and industrialization. However, he did not live to see the full fruits of his labor: Kuibyshev passed away in 1936 from coronary artery thrombosis at the age of just 46.

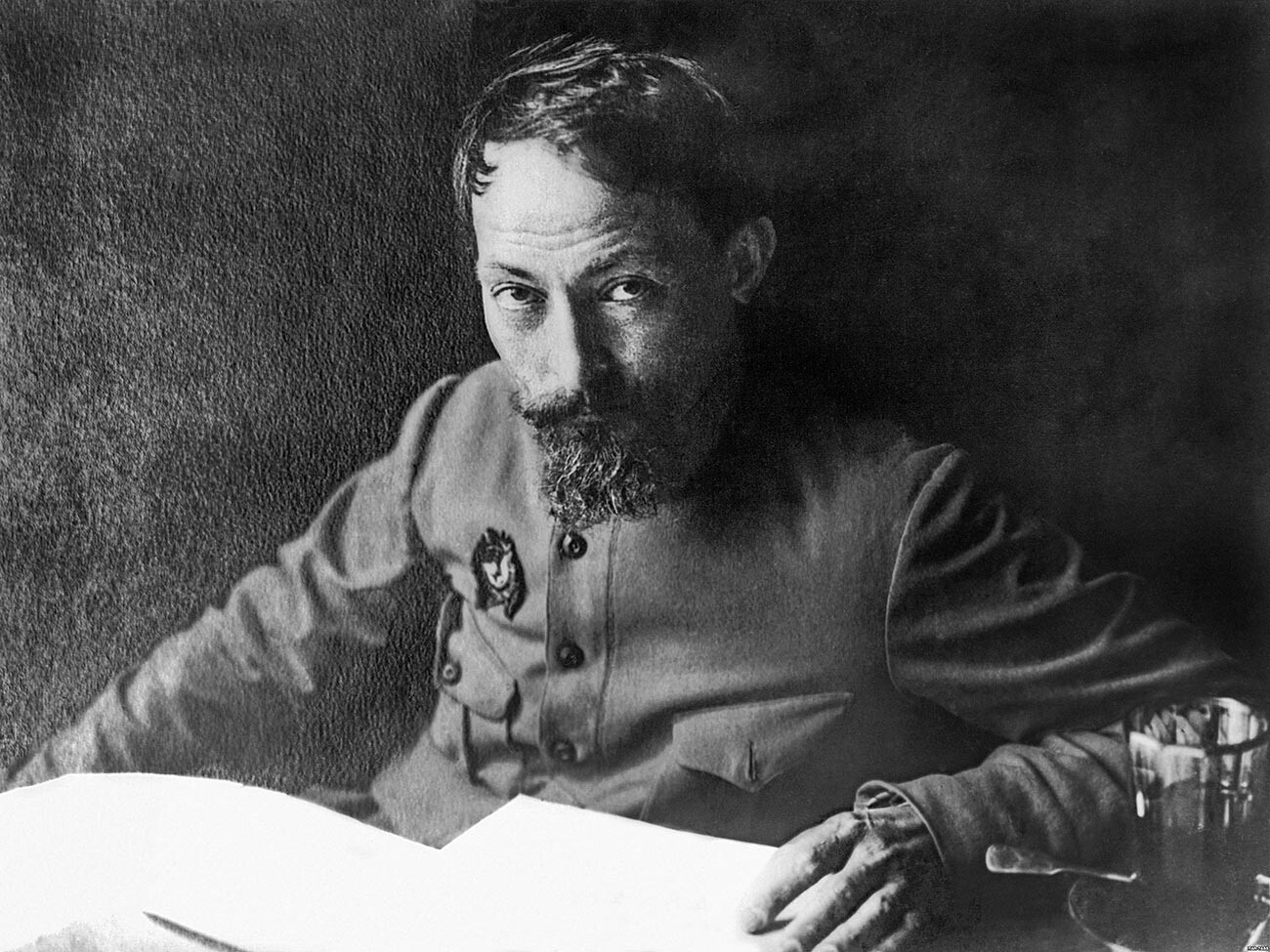

His name is inextricably linked to the birth and rise of the Soviet secret police. The son of a Polish nobleman, the owner of the Dzerzhinovo farmstead (near Minsk in modern-day Belarus), Felix Dzerzhinsky became one of the founders and the first head of the All-Russian Extraordinary Commission for Combating Counter-Revolution and Sabotage (Cheka for short), the predecessor of the Soviet KGB and the Russian FSB.

“Dzerzhinsky was the harshest critic of his brainchild…” recalled Vyacheslav Menzhinsky, an associate and later the successor of Dzerzhinsky. “He constantly dismantled and rebuilt the Cheka, reorganized its people, structure and methods time and again, above all fearing that the Cheka and its successor OGPU would not get overgrown with red tape, paperwork, indifference and routine… One thing was important to him: that the new organizational form of the Cheka, its new methods and approaches, continued to achieve the main goal of decomposing and defeating the counter-revolution…” wrote Menzhinsky.

“Iron Felix” was one of the ideologists and leaders of the mass purges known as the Red Terror, which he himself defined as “the intimidation, arrest and destruction of enemies of the revolution on the basis of their class affiliation or role in past pre-revolutionary periods.”

On March 5, 1953, after the death of Joseph Stalin, Georgy Malenkov took over as chairman of the Council of Ministers of the USSR and de facto leader of the Soviet state. A nobleman by birth, he hailed from a notable family of clergymen in the city of Ohrid, present-day North Macedonia, some of whom had emigrated to Russia.

Malenkov did not stay at the helm of the state for long, losing out to his political rivals less than two years later. “Officially, he was blamed for various political miscalculations and blunders,” opined Soviet statesman Mikhail Smirtyukov. “But in actual fact, his comrades in the collective leadership simply could not forgive him for trying to make important decisions without consulting them. Like Stalin.”

In early 1955, Malenkov was removed from power by Nikita Khrushchev, but served for some time as energy minister. After an unsuccessful attempt to repay Khrushchev in kind in 1957, Malenkov was expelled from the Communist Power and “internally exiled” to Kazakhstan. He died on Jan. 14, 1988, not long before the collapse of the Soviet Union.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox