How shamans were persecuted in the Soviet Union

Bogdan Onenko, 65, from the village of Nay Khin, some 8,500 kilometers from Moscow, was arrested on September 12, 1937, and executed by firing squad 40 days later. That same year, the first representative of the Nanay district executive committee, B. Hodzher, was accused of “concealing and protecting shamans and providing false evidence, claiming there were only six shamans in the district, while a census revealed that there had been 130 individuals”. All shamans had lost the right to be elected.

These are actual historical facts that can be gleaned from archives, detailing everyone who suffered bolshevist persecution. Soviet rule had targeted everyone who belonged to a different ideology and this battle spilled over beyond just political parties. The atheistic state liquidated all religious faiths and their adepts, from Orthodox Christianity to Islam and Buddhism. Shamanism, as a traditional worldview of the peoples of Siberia and the Far East, was also on that list.

“They corrupted the kolkhoz”

“When I was little, we lived in the village of Rezemovo… We, kids, were warned in advance that there would be a ‘dark house’- that the home would go dark. This was done to prevent us from being frightened if we hear something unusual or scary,” Elizaveta Kopotilova, 63, says, recollecting her childhood encounter with the village shaman.

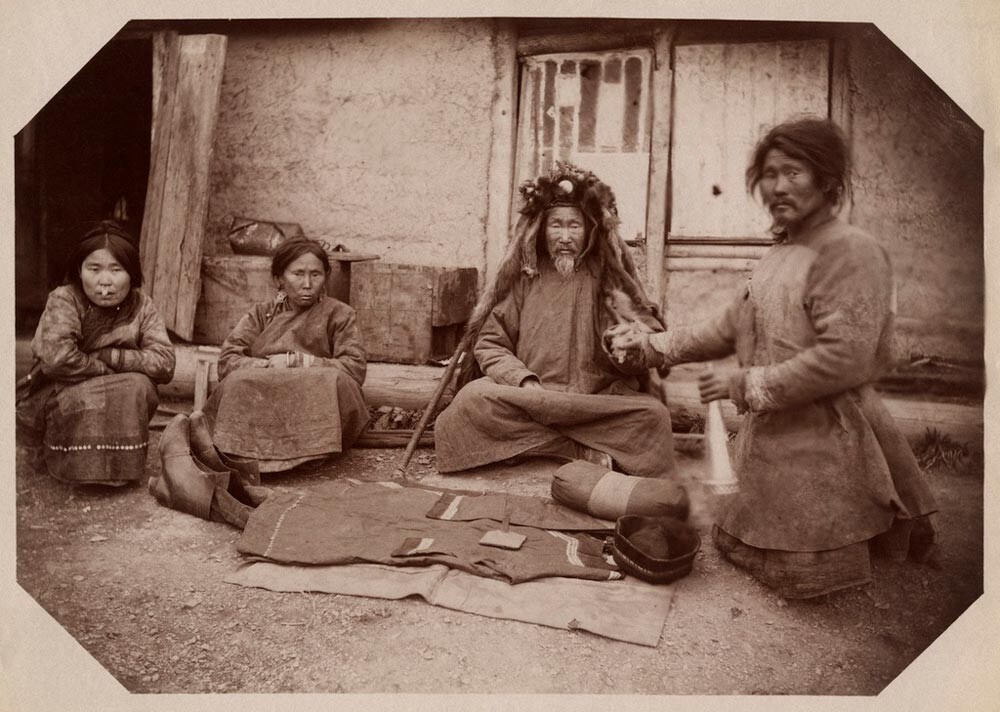

Funeral day

Funeral day

And so it was: in the darkness, an eerie sound had begun to spread, as though someone was running. “It wasn’t loud, but rather soft… but you could clearly make out pronounced thuds, that were getting closer and closer… And the sound would grow louder and louder. And then, it ceased, as if someone had stopped. And then, on the contrary, it would begin to grow quieter, until finally disappearing completely, as though someone was in the process of leaving. The lights were turned back on, and the adults resumed talking, discussing something,” she remembers.

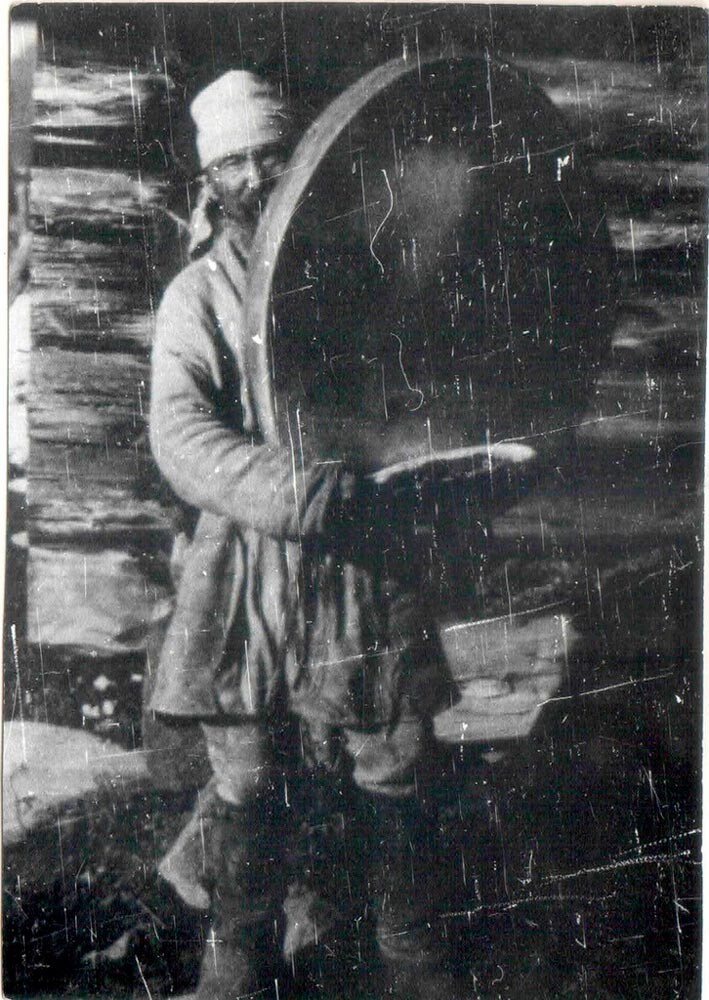

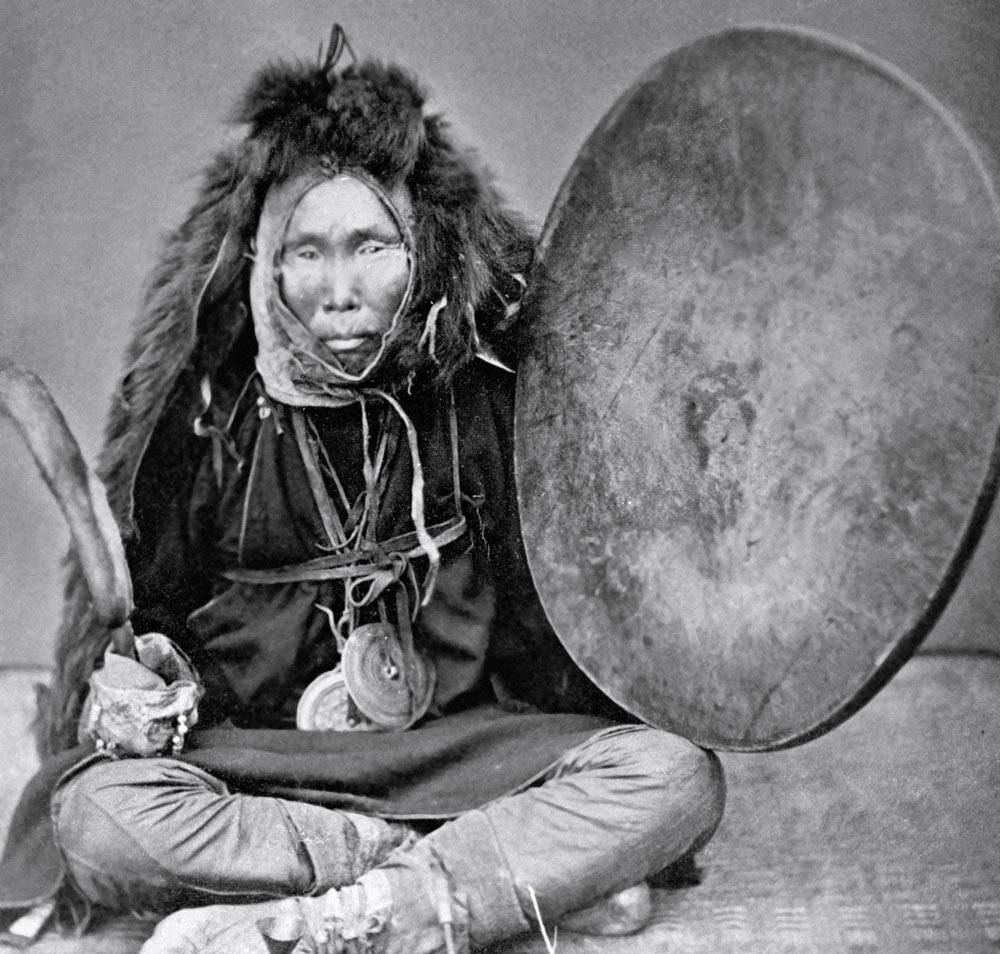

Shor Shaman, 1930 - 1940

Shor Shaman, 1930 - 1940

This took place in Yugry, which is the territory of present-day Khanty-Mansiysk Autonomous Region. Yugry, since time immemorial, was considered the cradle of Siberian shamanism. One can easily surmise that the above story took place during the culture’s purge by the usage of the phrase “dark house” - this is when they would cover up the windows and perform rituals in complete darkness, so as not to attract attention from the outside.

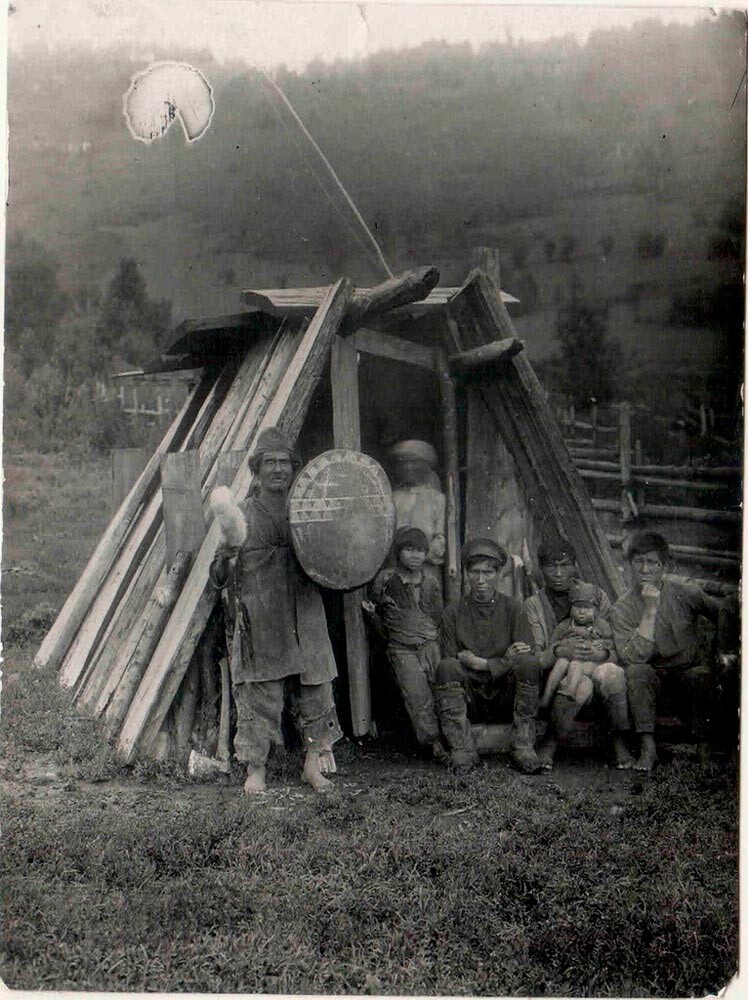

Shalash hut, 1927

Shalash hut, 1927

Shamanic kamlaniya (“rites”) were visited by the whole village. People would come to cure their ailments, pray for their dead relatives, ask the spirits for health for their livestock - to end their mass morality and to provide good weather. Shamanas were always revered and listened to; but Soviet rule did not want to share power and authority and saw shamanism as “opium for the people”, referring to them as “hostile” elements and enemies of the state.

It all started in the 1920s, almost after the formation of the new Soviet state. Shamans were promptly stripped of electoral rights in every election, including at village and district levels. In practice, this meant that such a person was excluded from the collective farming (kolkhoz) system and, as a result, deprived of all means of subsistence. Some village committees voted on evicting shamans from the villages, which meant losing their homes, on top of everything.

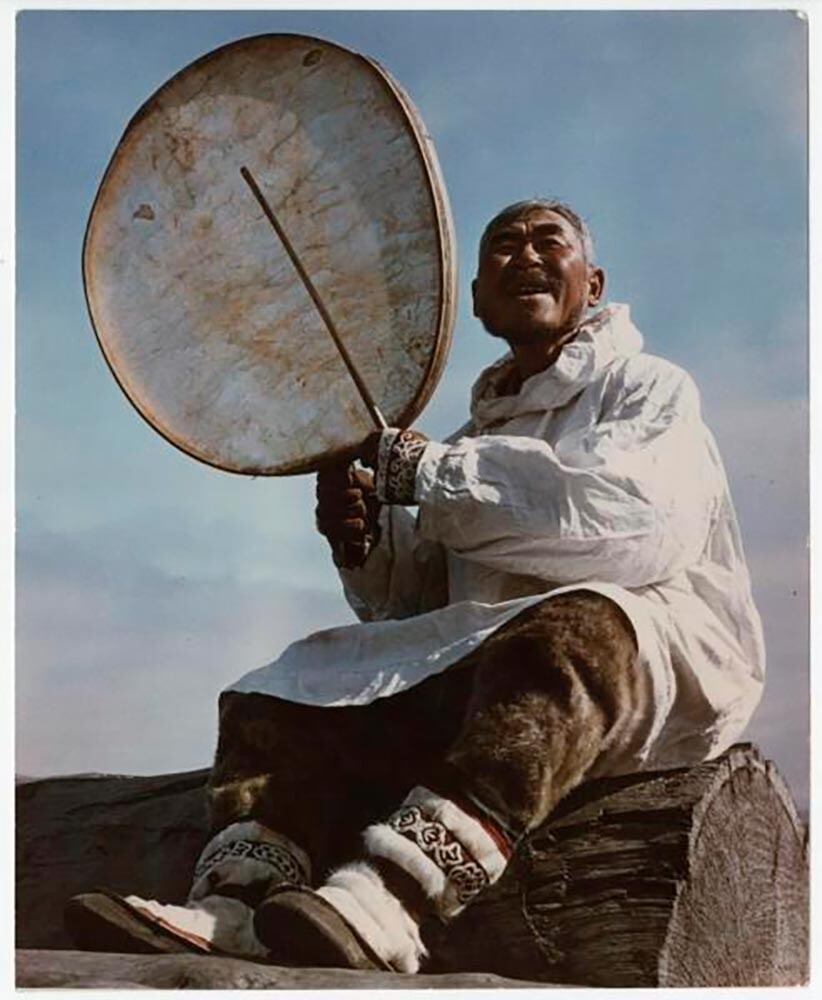

Shaman, 1972

Shaman, 1972

The first wave of the anti-shamanic campaign - masqueraded as part of the fight against the kulaks (peasants with ownership rights, who used hired labor to work the lands). Together with the shamans, all other unfavorable social groups went under the hammer: priests, merchants, Cossacks, tradesmen - their properties all confiscated.

“The Shaman ‘Beldy Pelkha’ (an individual peasant) has used his influence to corrupt the kolkhoz,” one of the reports stated. The kolkhozniks, who had close ties to him, supposedly “left the kolkhoz fishing brigade for another aquifer, and aren’t fulfilling their quotas (instead of 35 centners [a unit of weight in parts of the former Soviet Union equal to 100 kg], submitting five and selling the rest)”.

In order to transition from local, unorganized attacks on religion and alternative spiritual practices to full-scale systematic persecution, the authorities in 1925 created the Union of Warring Atheists. This civil organization then began a hearts-and-minds campaign against religion at the public level. These bezbozhniki (“atheists”) began to hold meetings, exhibitions, publishing literature, creating networks in factories, kolkhozes and universities and so on. They referred to shamanism as a “vengeful and fierce religion”, from which the population was “tired”.

However, these measures didn’t have the desired effect. Shamanism had gone underground.

Dark years

The 1930s turned out to be the most repressive period when it became clear that the program to completely wean the population off alternative practices had failed. Only the form of the rites changed: instead of the traditional Siberian drum (which was very loud), shamans would use an ax, which they would hang around their necks, with the blade pointing toward the face. The rituals themselves became increasingly quieter. And gatherings would be held far more carefully: informants would say - “you could never hide the fact of grannies all entering the same house”.

The latter would become especially risky. Raids had begun to be commonplace. Any cult parafernalia is confiscated and burned. There were cases when the children of shamans entered commnist organizations and confiscated those items from their own parents. The archives tell us of one Pavel Tumali, who took his father Podya Tumali’s drum and belt and threw them into the Amur river, adding: “Don’t embarrass us!”

Because of that, shamans would increasingly have to travel to fields and hide in the woods to carry out their rites. Many preferred to leave the practice altogether, fearing arrest and a possible execution. Although, some researchers note that mass repressions and shootings never took place. This happened allegedly on a case by case basis.

Simpler punishments, taking on the form of fining or firing, were commonplace. This included not just shamans, but everyone who appeared to “not be fighting shamanism hard enough”. In 1937, a note in a report read: “The shamans took advantage of the village counsel and management’s lax work. With the new Constitution in place, they only increased their activities. If, in 1935, only one shaman was active - Beldy Pelkha, there are nine active at present.”

Not a true end

With time, after World War II had ended, the ban on shamanic activity had not gone away. It would exist all the way until the 1980s, but only symbolically.

Painting "Exile of the Shaman. Artist A.G. Shavkerin. 1960.

Painting "Exile of the Shaman. Artist A.G. Shavkerin. 1960.

In the 1960s, shamans still faced fines for performing rites, but that did nothing to stop them: they simply went off the grid - gathering in houses with lights turned off, or after midnight, with windows boarded up and so on. And by the first half of the 1980s, not one official report contained even a small detail about the supposed fight against alternative spiritual practices. Shamans, according to official data, had supposedly disappeared altogether in some regions. For example, a Khabarovsk publishing house (a region in the Far East) in 1982 released the book ‘The Tale of the Last Shaman’ by A.A. Passar.

Of course, this didn’t mean the end of shamanism in practice. After many years of persecution, it changed its face. If, in Yakut and Buryat villages, its image stayed unchanged, surviving years of deprivation, the situation was different with regard to the far less popular Kyrgyz shamanism, which mutated into something else: Kyrgyz shamans don’t bang drums - that element is gone for good; they also don’t wear special costumes, but retain only certain attributes of their religion, such as the scepter and lash.