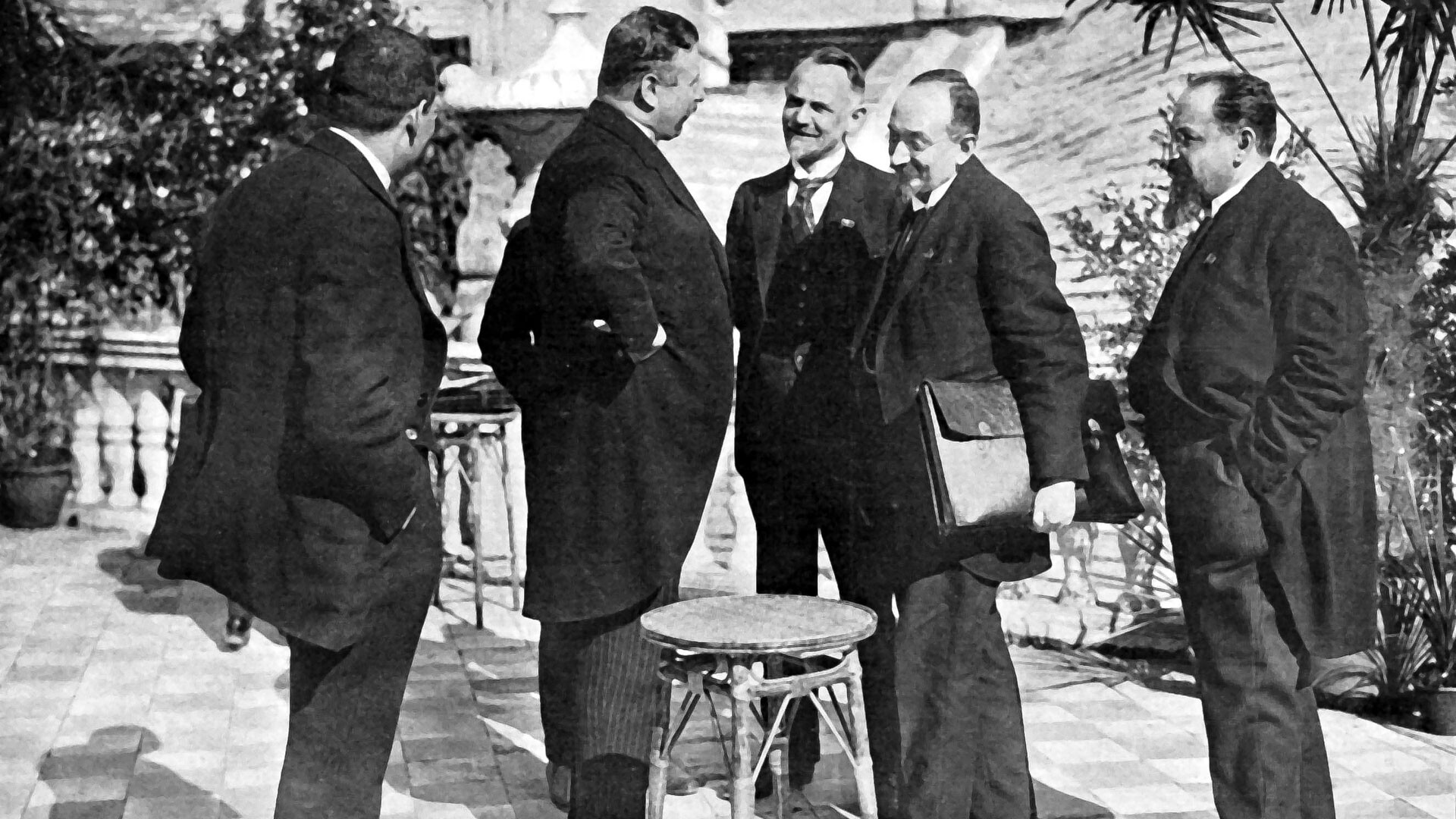

Russian and German diplomats in Rapallo.

Photo12/UIG/Getty ImagesOn April 16, 1922, Western European powers woke up to a shocking development. In Rapallo, near Genoa, Soviet Russia and the Weimar Republic signed a treaty in order to establish diplomatic relations, resolve disputes, and set up long-term cooperation. By doing so, both rogue states sent a clear message to the Entente that they did not intend to perish in international isolation.

It was far from the best period in history for Germany and Russia. The Germans were declared the main culprits in the outbreak of World War I, and were weary of the weight of the exorbitant reparations laid on them. The Russians were practically cut off from the rest of the world since the only countries that recognized the newly formed socialist "state of workers and peasants" were Afghanistan, Estonia and Latvia.

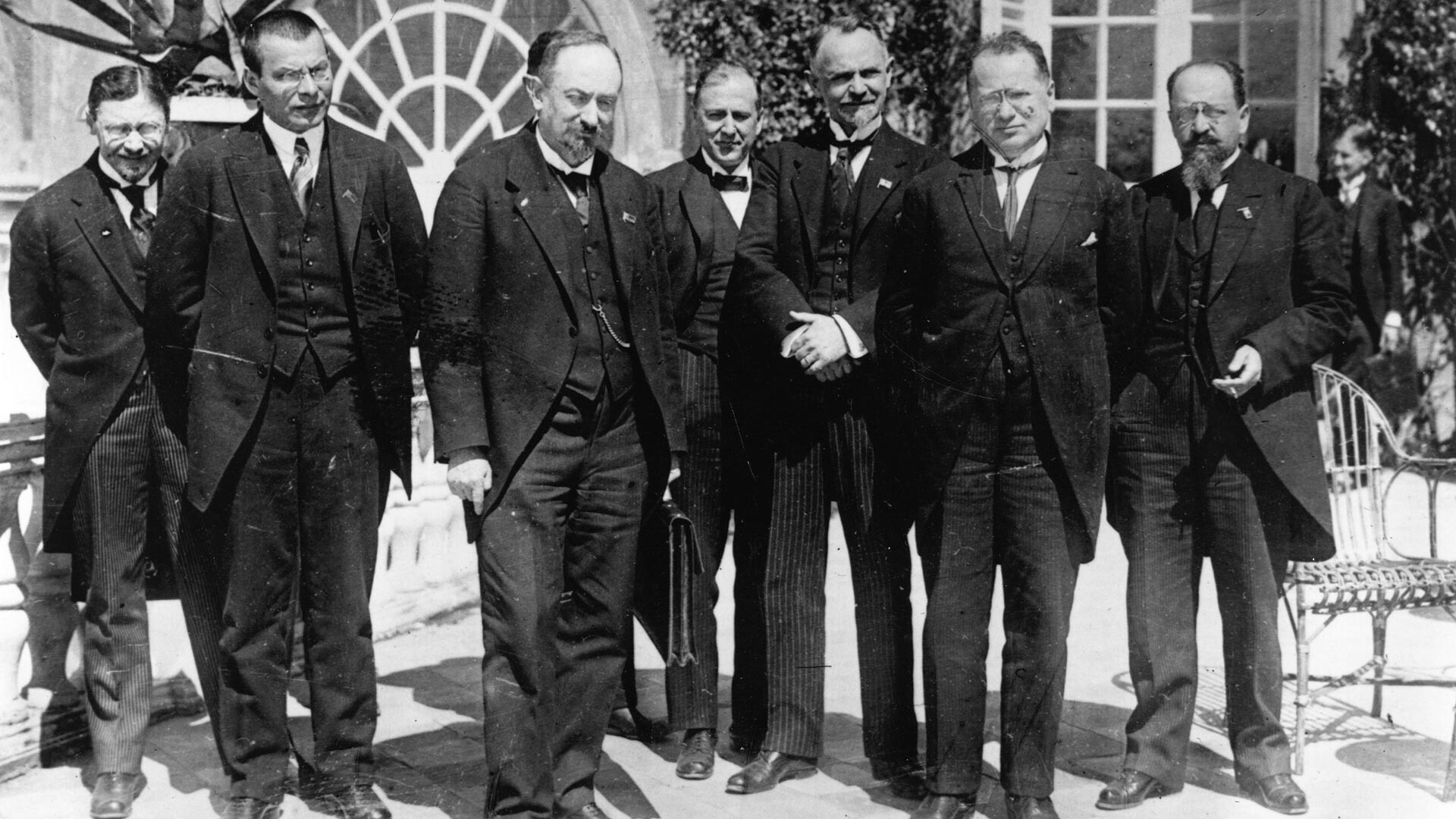

Soviet delegation in Genoa.

Public DomainThe Entente powers were convinced that Germany and Russia were under their thumb, and that it would be Paris and London that would pave the way out of their difficult situations. No one had expected a settlement between two ideologically distant "outcast" states that, until recently, had been enemies on the battlefield.

The journey to Rapallo for the two countries began immediately after the war ended. Having no formal diplomatic relations, they nevertheless started taking small steps to engage economically and politically.

"Breaking the Versailles diсtate can only be achieved by close contact with a strong Russia," argued Reichswehr commander-in-chief General Hans von Seeckt: "Whether we like Communist Russia or not is irrelevant. What we need is a strong Russia with wide borders - on our side... For Germany it is important to untie the entanglements of the Entente via Soviet Russia."

Hans von Seeckt.

Musvage (CC BY-SA 4.0)Moscow, in turn, was looking for points of contact with Berlin to break through international isolation and punch a hole in the united Western anti-Soviet front.

The historic treaty was signed during the Genoa International Conference, to which the British and the French invited representatives of the Bolshevik government. The official mission of the event, which was attended by nearly thirty states, was proclaimed as "the final restoration of European peace."

Full of hope, the Soviet delegation, headed by Georgy Chicherin, People's Commissar of Foreign Affairs, set out for northern Italy in the spring of 1922. However, for Soviet Russia to return to the family of European nations, it was required to pay the debts of the Tsarist and Provisional governments, compensate the former foreign owners for their nationalized property, open the country to foreign capital, and stop its revolutionary propaganda around the world.

Georgy Chicherin in Genoa.

Public DomainThe Soviet delegation, for its part, stated that it was ready to consider questions of compensation, but only after the Entente had fully compensated Soviet Russia for the multimillion-dollar damage inflicted during the intervention. Since the British and the French were not going to take such a step, the negotiations reached an impasse.

The Russians then decided to negotiate with the Germans, who also realized by then that the conference would not provide them any relief from their difficult economic situation.

On the fifth day of the Genoa Conference, the Soviets proposed to the German delegation, headed by Walther Rathenau, Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Weimar Republic, a clean slate in bilateral relations by immediately restoring diplomatic relations and renouncing the financial losses caused by the war and the revolution. The Germans were to recognize the nationalization of their private property in Russia, and the Russians were to give up their right to war reparations.

Walther Rathenau in Genoa.

A.& E. Frankl/Ullstein bild/Getty ImagesThe German delegation spent the whole night discussing the Soviet proposals. The Weimar Republic could conclude the first equal treaty since the humiliating Versailles and, moreover, do so with the most important power in Eastern Europe. At the same time, the Germans feared a harsh reaction from the British and the French.

After the "meeting in pajamas" (as that night was nicknamed in the West), Rathenau decided to sign a treaty with the Bolsheviks, which took place on April 16 in Rapallo. Among other things, the parties agreed to long-term economic cooperation and also informally expressed their willingness to establish military ties to circumvent the restrictions imposed by the Allies.

"The Rapallo Treaty of 1922 was the result of a long and complicated struggle for the right to independent and separate economic cooperation between Russia and Germany outside the mandatory international capitalist front, which represented a kind of trap for Russia," Georgy Chicherin wrote in his article "Five Years of Red Diplomacy".

The Russian-German treaty had a bombshell effect. The Entente instantly lost one of its most important leverages with Soviet Russia. "This will shake the world! It's the biggest blow to the conference," said Richard Childe, the American ambassador to Italy, present in Genoa as an observer.

Soviet diplomats in Rapallo.

Topical Press Agency/Getty ImagesRathenau was immediately pressed by the British and the French to tear up the agreement. Suppressed, he even went to Chicherin with this, but was told it was no longer possible.

There were cries for an immediate end to the conference among European diplomats, but this idea was reluctantly abandoned. One way or another, some agreement had to be reached with the colossus in the East.

Both Moscow and Berlin were pleased with the agreement, which became the first step in the long-term cooperation between the two countries. Along with the rapid growth of trade, military cooperation also began: the Junkers plant was soon opened in the Soviet Union, and the Reichswehr aviation and tank schools began operating. However, after the Nazis came to power in Germany in 1933, all such joint projects were immediately shut down by the Soviet side.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox