In the midst of the Cold War, security services on both sides of the Iron Curtain had to stay vigilant and look out for spies planted by the enemy. The Soviet KGB was notorious for its ruthless fight against the CIA spies operating undercover in the Soviet Union.

To help its agents detect a spy among foreign citizens who legally came to the USSR, the Soviet secret police drafted a document titled ‘How to detect a foregn spy’.

The manual, which can be found online, lists a number of traits that the KGB thought to be inherent to spies operating in the USSR. While some of the points are fair, others sound as if they were borrowed from a James Bond book.

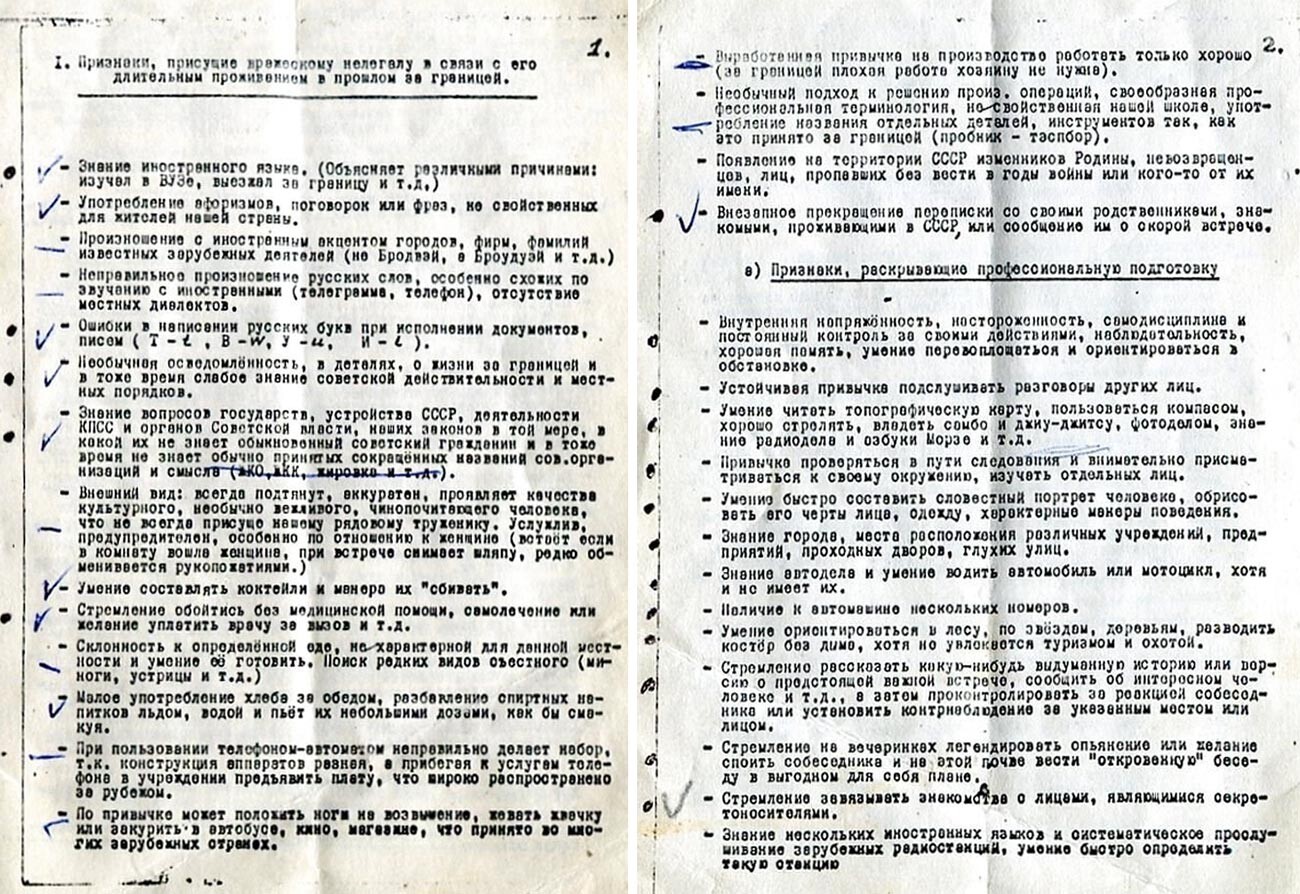

The KGB manual is divided into chapters each dedicated to different aspects of his life in the USSR. Some parts detail his handling of documents, while others advise Soviet counterintelligence officers to look for blind spots in a biography of a potential spy.

Yet, the most interesting parts of the KGB manual describe a spy’s appearance and his tastes in alcohol and women.

“Appearance: always neat, tidy, shows the qualities of a cultured, unusually polite, respectful person, traits that are not always inherent in our average worker. He is helpful and courteous, especially to women (he stands up if a woman enters the room, takes off his hat when greeting and rarely shakes hands),” reads the manual.

According to the KGB, a foreign spy was always a gentleman with elegant taste and a craving for luxury.

A typical Cold War spy appreciated rare edibles like oysters and lampreys. Unlike a typical Soviet worker, he was believed to refrain from eating bread and knew how to properly fix a cocktail.

An foreign intelligence agent “mixes alcoholic beverages with ice, water and drinks them in small doses, as if savoring them,” says the manual.

Given the assumption that a spy has unlimited resources at his disposal, the KGB deduced that a clandestine operative would not be too interested in the size of his Soviet salary.

“He is looking for a job with a simplified registration and a flexible schedule. Demonstrates indifference to his future salary,” reads the manual.

At the same time, the KGB assumed a spy would be inclined to please his bosses by working harder than an average Soviet laborer. A rather ironic explanation was provided to support this argument.

A spy has “developed a habit of working only well in production [because] foreign employers do not tolerate bad work abroad”, states the manual.

Of course, nobody is perfect… not even a foreign spy. And the KGB knew it. The manual also includes traits that were seen as rude in the USSR, but were believed to be typical for people who grew up in the West.

“As a habit, he may put his feet up on an elevated platform, chew gum or smoke on the bus, in a movie or in a store, as is customary in many foreign countries,” says the manual.

A foreign spy would also have a “nasty” habit of “eavesdropping on other people’s conversations”.

Besides the somewhat funny James Bond style tips, the manual draws a fair portrait of a person who values privacy, seeks out secret information and gives himself away by adhering to habits inherent to residents of Western countries.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox