“A shopkeeper in St. Petersburg had a beautiful Siberian cat, a huge one. The owner and his neighbors loved the cat and even the local policeman often came up to pet it. But, suddenly, the cat disappeared and the shopkeeper wept bitterly over his loss. Two days later, he learned that the cat was seen in the park and that it was tied to a string and was sold for 25 roubles silver by a German skipper among the rare animals brought from abroad. The shopkeeper ran to the skipper and explained the case, but the skipper did not want to hear anything and in his excuse kept repeating: “Danzig, Danzig,” and the shopkeeper said: “What Danzig? - It’s not Danzig, it’s my purr-fect, which the whole market knows!”

But the stubborn German wouldn’t give up the cat. Then, the enraged shopkeeper ran to the market and gathered some of his neighbors and the policeman. A heated argument began again in the square, but finally, with the help of other German skippers, the cat’s false owner gave it back to its real owner.”

Count Alexander Benckendorff, 1835

Public DomainThis nice urban legend would hardly have had a chance to make historical chronicles if not for the Third Department of His Imperial Majesty’s Own Chancellery, the tireless eye of the sovereign, who tried to look into the lives of all his subjects – from the shopkeeper to the prince. Agents of the secret police carefully collected all the gossip of the city (including such stories as the one above), so its documents are just a treasure trove and an encyclopedia of Russian life, except that, in the memory of the people, the Third Department is imprinted very differently.

The building in St. Petersburg where the Third Department was housed, Fontanka Embankment, 16.

GAlexandrova (CC BY-SA 4.0)On December 14, 1825, representatives of prominent aristocratic families, later called the ‘Decembrists’, attempted to take advantage of the delay in the succession to the throne by organizing a military mutiny and eliminating future Emperor Nicholas I. The most desperate heads even offered to kill the entire imperial family, but the defenders of the throne prevailed. A special role in the defeat of the revolt was played by General Alexander von Benckendorff, a hero of the 1812 Patriotic War and a personal friend of the emperor. On the day of the Decembrists uprising, he commanded the government troops and then was a member of the Commission of Inquiry into the Decembrists’ case.

Inspired by the experience of the legendary Napoleonic Minister of Police Joseph Fouché, in 1826, Benckendorff headed a new body of political investigation – the Third Department of His Imperial Majesty’s Own Chancellery. In addition, Benckendorff established the post of Chief of the Gendarmes (and took it himself in 1827) and created the Independent Corps of Gendarmes. Thus, the higher police and the gendarme units were united under the command of one person.

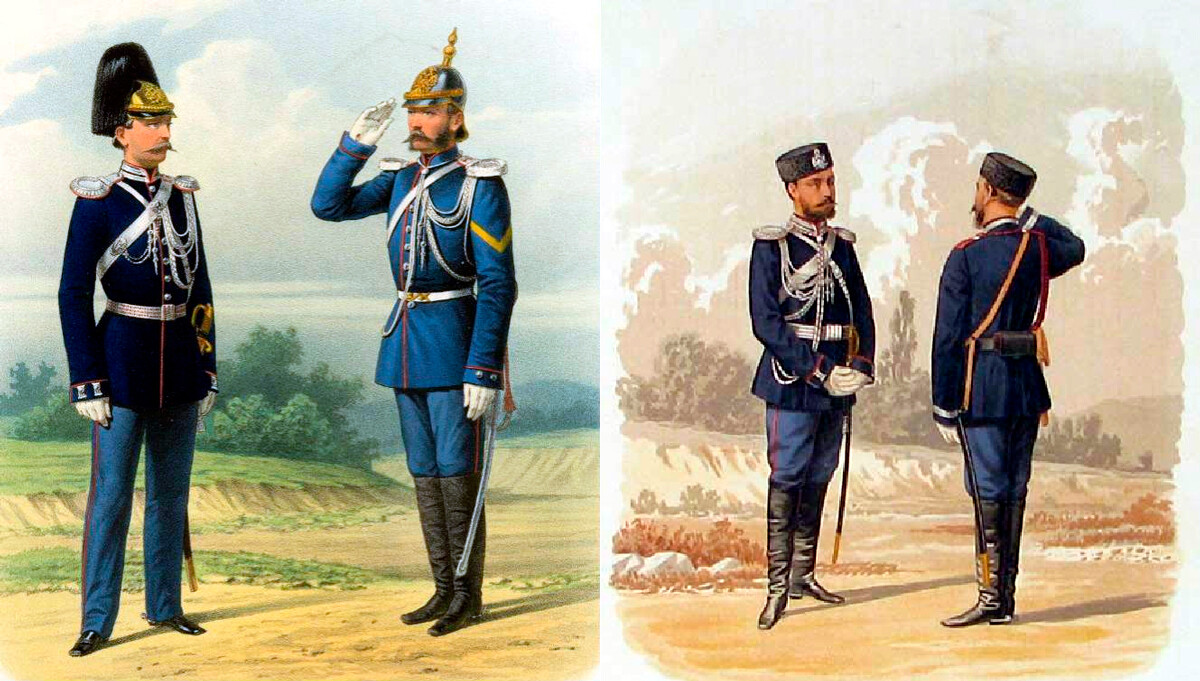

The uniforms for the Corps of Gendarmes

Public DomainAccording to the plans of Benckendorff, his brainchild was not only to protect the throne, tame riots and root out dissent, but, above all, to serve the public good: to expose the embezzlement, to combat bureaucratic abuses. “To bring the voice of the suffering mankind to the throne of the tsar and to put the defenseless and voiceless citizen immediately under the highest protection of the Emperor” was the goal that the chief gendarme of the Empire urged his subordinates to follow. The legend of the handkerchief, allegedly given to Benckendorff by Nicholas I as an illustration of the assigned tasks – to wipe the tears of the unfortunate, appeared not without reason.

"Pushkin and Benckendorff" by Alexander Kitaev

Mikhail Ozersky/SputnikThe authorities tried to recruit yesterday’s rebels and freethinkers. Benckendorff invited poet Alexander Pushkin to join the Third Department and his brother Lev – to the Corps of Gendarmes. But, the aristocracy was in no hurry to respond to this call, because five Decembrists were hanged by Nicholas I’s order and their comrades – also members of noble families – were imprisoned in Siberia. This alone poisoned the reputation of the Department and the police itself was deeply despised in Russian society.

Here is how a contemporary described Benckendorff and his close associate Leontius Dubelt: “There was a time when every word said in defense of these two men could only stain the defender himself, to cast suspicion on him of servility or proximity to the Third Department.” Allegedly, Benckendorff’s own aide-de-camp refused to serve him for fear of public censure.

At first, there were fewer than 20 men in the Third Department and, by the time it was liquidated in 1880, there were 72. They monitored foreigners, revolutionaries, students, writers, sectarians and counterfeiters, were engaged in counterintelligence and censorship, wrote reports on public sentiment and all significant events in the empire.

The secret police also had another unexpected, but important role: the resolution of family conflicts. For example, in 1870, Gendarme Lieutenant Colonel Knop and his superior, Count Peter Shuvalov, head of the Third Department, stood up for the wife of the famous painter Yulia Aivazovskaya, whom her husband was beating ruthlessly. A conversation with them was enough to tame the ardor of a rebellious artist and ensure the safety of the unhappy wife and her daughters.

The assassination of Alexander II

Public DomainBy the end of the 1870s, Russia was overwhelmed with revolutionary terror, which the Third Department was no longer able to cope with. Former revolutionary Lev Tikhomirov wrote about that time: “The Third Department was in a weak and disorganized state and it is difficult to imagine a more trashy political police force than that time. In fact, such a police force was a real gift for the revolutionaries; with it in function, one could do wonders with a serious plan of a coup…”

The emperor was hunted like a wild beast: eleven attempts were made on Alexander II’s life. In 1880, at the height of this bloody manhunt, when the powerlessness of the Third Department became quite apparent, it was abolished and replaced by the Police Department of the Ministry of the Interior. But, the measures that were taken could no longer save the tsar and, on March 1, 1881, he was killed by the bomb of Ignatius Grinevitsky.

As the years passed, the revolutionary terror grew more and more rampant, so much so that, at times, newspaper editors prepared obituaries for newly appointed governors well in advance and taking the post of Minister of Internal Affairs sometimes meant signing your own death warrant. So, the successors of Benckendorff, officials of the Police Department, no longer had the time, energy or desire to describe the petty tangles of life, such as the story of the shopkeeper and his Siberian purr that we began with.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox