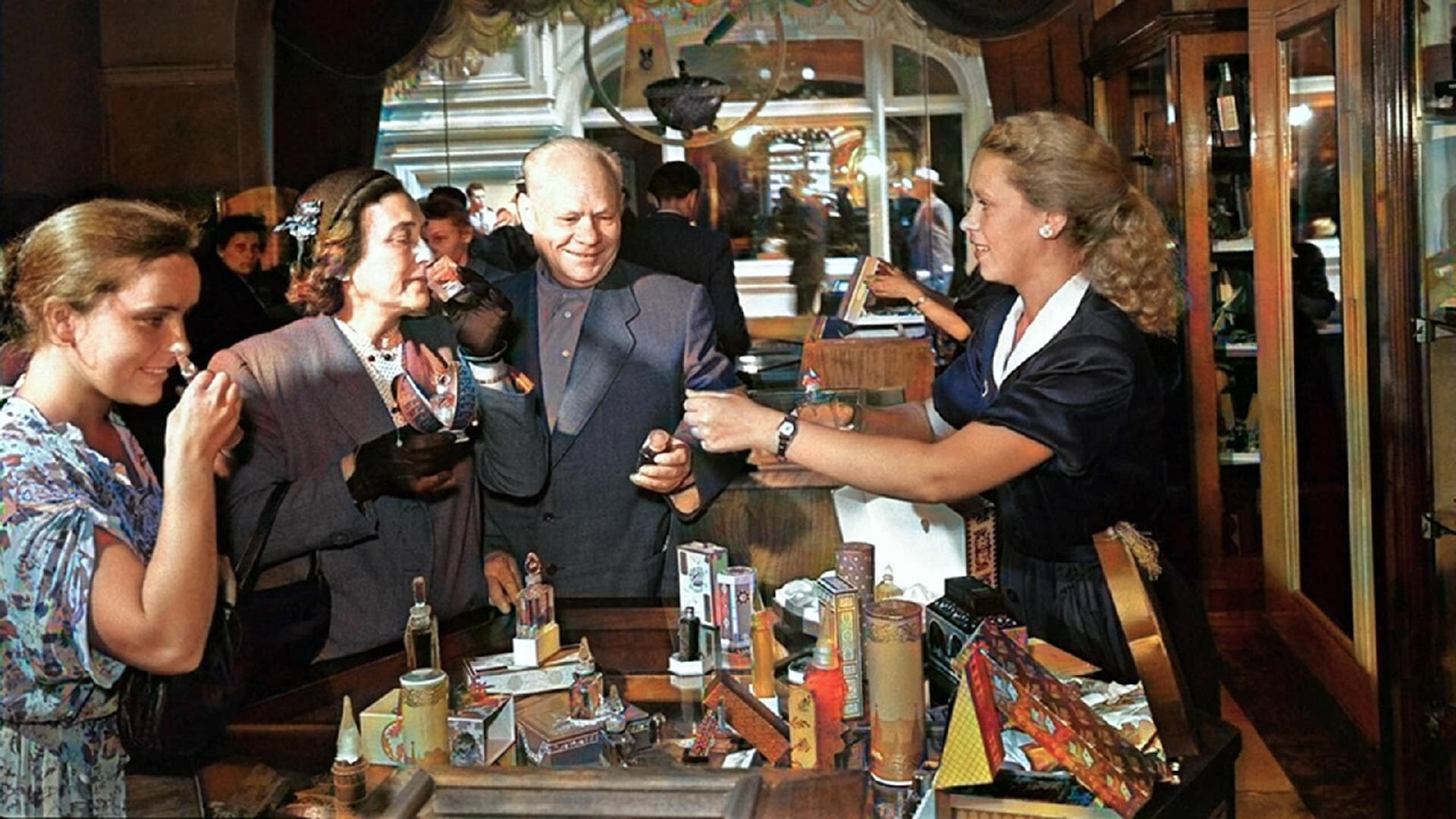

Perfume department at Moscow’s GUM store, 1954.

Mark Redkin/TASS/russiainphoto.ruWe’ve already written about what was sold in Soviet grocery stores, so now let’s take a look at the windows and counters of department stores. Where could Soviets buy clothes, shoes, household goods and other necessities?

A store window with dishes, 1960s.

Robert Diament/MAMM/MDF/russiainphoto.ruThe Soviet economy was planned and the amount of required goods was estimated by special organizations, after which everything was distributed to the regions. The best provision was, of course, in Moscow and Leningrad (now St. Petersburg), as well as in the large industrial cities. People from all over the Soviet Union went to them en masse in search of goods.

‘TsUM’s main stairs, 1946.

Arkady Shaikhet/MAMM/MDF/russiainphoto.ruBack in the early 1920s, the Mostorg Trade Department was established in Moscow and its main store was the ‘TsUM’ (Central Universal Store) near the Bolshoi Theater. The store building itself was constructed in 1885. There, you could find things from Hungary, Poland and the Baltics. And it was one of the first stores in the country with self-service.

‘Synthetic’ store in Moscow, 1960s.

Ivan Shagin/MAMM/MDF/russiainphoto.ruMostorg department stores were also built in the suburbs of the city and they were designed in a similar Constructivist style: as a rule, the building consisted of four stories with huge stained glass windows and a minimalist decoration. In the 1950s, every major city in the country had its own ‘TsUM’.

A department store in Novosibirsk, 1954.

Mikhail Ozersky/SputnikHowever, the main store of the USSR was still the ‘GUM’ (State Department Store) on Moscow’s Red Square. It was built in 1893, following the model of a European arcade, with gallery lines under a glass roof. In the mid-1950s, it was renovated and made into a model Soviet store.

Inside the ‘GUM’, 1970.

Denisenko/SputnikThere was literally everything, from combs to the most trendy dresses. The best samples of the Soviet light industry were displayed in the showcases. On the first floor, there was a grocery store with a gastronomy section. And the symbol of GUM has always been ice cream in a waffle cup, which is still sold there today.

One of ‘GUM’s show windows, 1950s.

Dmitry Baltermantz/MAMM/MDF/russiainphoto.ruGUM was open to anyone, but there were sections hidden from ordinary people, where only artists and officials shopped and many Soviet citizens were not even aware of this.

‘Beryozka’ store, 1974.

Yu.Levyant/SputnikIn the capitals of the Soviet republics and other large cities, there were luxury ‘Beryozka’ stores, where goods were sold for foreign currency, either to tourists or Soviet citizens who returned from foreign business trips, i.e. diplomats, construction workers, cultural workers. In short, not many people could get into ‘Beryozka’.

At the ‘Gifts’ store, Moscow, 1967.

Isaak Tunkel, Dmitry Ukhtomsky/MAMM/MDF/russiainphoto.ruIn the 1960s, Soviet authorities came to the conclusion that self-service department stores were the most prospective type of trade. The construction of similar shopping centers spread across the country. Prices in the USSR were also set by the state and they were more or less the same from Kaliningrad to Vladivostok, although, in some places, there was an increased markup, due to transportation costs.

A woman with her daughter in the shoes store in the town of Sovetsk, Kaliningrad Region, 1988.

Vladimir Fedorenko/SputnikFor children in the cities of the USSR, there was a network of stores called ‘Detsky Mir’ (“Kids’ World”) with toys, clothes, shoes and goods for school.

A store for kids in Leningrad, 1950s.

Vladislav Mikosha/MAMM/MDF/russiainphoto.ruIn Moscow and Leningrad, department stores began to open with things from other socialist countries: it became possible to buy toys from the DDR, boots from Yugoslavia and cosmetics from Czechoslovakia.

At the ‘Vlasta’ store, 1975.

Roman Denisov/SputnikPrices were high: in the late 1970s, one could pay more than 50 rubles for foreign shoes and 180 rubles for a coat when monthly salaries were just 150-200 rubles. Soviet shoes, meanwhile, cost 10-15 rubles and a coat about 60 rubles.

A happy lady after purchasing Italian boots in Yaroslavl,1990.

Sergei Metelitsa/TASSThis is not to say that there was nothing in the remote regions, but the rural areas were much worse supplied than the industrial cities, with only the bare necessities. Locals had to travel to regional centers to find more or less acceptable clothes, shoes, gardening tools or lamps. And they rarely dreamed of foreign goods.

A kolkhoz store in Kursk Region, 1957.

M.Radin/MAMM/MDF/russiainphoto.ruIn some regions, there were multi-monthly “virtual” lines for the purchase of necessary household goods - which meant that even if you had money, you could not just buy a refrigerator. Interestingly, sometimes the system brought surprises and in a small rural store you could occasionally see, for example, imported alcohol or musical equipment, which was expensive and, therefore, not in demand and gathering dust on the shelf.

A rural department store in Rostov-on-Don Region, 1954.

A.Agapov/SputnikIn the late 1980s, the shortage of many goods in the country was felt especially hard. There emerged the concept of “sausage” trains - it was when residents of the regions traveled to major cities for the most deficit “sausages”, as well as clothing, footwear, household chemicals and electronics.

A department store in Rostov-on-Don, 1989.

Vyacheslav Bobkov/SputnikThe main attribute of that time was the hours-long lines outside stores where something was “thrown away” - and often people didn’t even know what they were standing there for. But, if there was a line, it must surely have been something worthwhile. Although, today, the shelves are full of goods for every taste, many people who remembered that time are still in the habit of stocking up.

A line in ‘GUM’, 1989.

Vladimir Vyatkin/SputnikDear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox