How many times did the Russians defeat the Mongol Golden Horde?

The Mongol invasion that spread across Rus’ (as medieval Russia is known) in 1237 was akin to an avalanche. It seemed nothing could stop the onslaught of the nomadic conquerors, who, without much difficulty, were crushing the forces of the Russian princes and taking even the strongest fortresses. Nevertheless, from time to time, the Russians managed successfully to resist the invaders. Thus, the Mongols had to lay siege to the small town of Kozelsk for a whole 50 days before they seized it, while they were thrown back altogether from Smolensk. But, major victories over the invading enemy were out of the question then.

Siege of Ryazan.

Siege of Ryazan.

In the end, Rus’ was subjugated and became politically and economically dependent on the mighty Mongol state of the Golden Horde, which lay near its borders in the southern steppes. Golden Horde khans began to levy regular tribute, as well as grant yarlyks (patents of office) to the Russian princes, giving them license to rule in their own lands. They relished pitting one prince against another, from time to time supporting one or other of the sides. It was during one such conflict that the Russian forces won their first major victory over the Mongols.

Basqaq (Mongol official, who was in charge of taxes and administration in a certain province).

Basqaq (Mongol official, who was in charge of taxes and administration in a certain province).

In the early 14th century, Prince Mikhail Yaroslavich of Tver and Prince Yury Danilovich of Moscow disputed the grand prince yarlyk, which gave its holder seniority over other Russian rulers. By marrying Konchaka, the sister of Uzbeg Khan, who had converted to Orthodox Christianity, Yury enlisted the support of the Horde. Despite this, on December 22, 1317, in a battle near the village of Bortenevo, the Tver army managed to defeat the joint forces of the Moscow ruler and Mongol commander Kavgady. Mikhail Yaroslavich knew that the enemy would not forgive him the ignominy he had brought upon them (especially after Konchaka died while in captivity in Tver). Without waiting for the arrival of a punitive expedition in his lands, in 1318, he voluntarily went to the Horde to be judged by the Khan and never came back alive.

Death of Mikhail of Tver.

Death of Mikhail of Tver.

In the middle of the 14th century, a political crisis known as the ‘Great Strife’ began in the Golden Horde - in the course of two decades, 25 khans were replaced on the throne. The Mongols waged a fierce power struggle among themselves, while not forgetting to plunder the Russian principalities, which, from time to time, managed successfully to fight back. Thus, in 1365, Bek (Prince) Tagai, who had been plundering the Ryazan lands, was crushed in a battle near the Shishevsky forest. Two years later, in a battle on the River Pyana, Emir Bulat-Timur was defeated when his forces invaded the Principality of Gorodets.

Battle near the Shishevsky forest.

Battle near the Shishevsky forest.

The culmination of the centuries-old Russian-Mongol confrontation was an encounter between the Principality of Moscow, which, by the 1370s, had become the main center of Russian resistance to the Horde and the powerful Beylerbey (Bey of Beys) Mamai, who had been extremely successful in bringing together the scattered parts of the Golden Horde under his authority. In 1378, on the River Vozha, the Russians managed to secure a crucial victory over an army dispatched by him: Five tumens (around 50,000 soldiers) were crushed and five commanders were left dead on the battlefield, including Murza (ruler) Begich, who had led the force.

Battle of the River Vozha.

Battle of the River Vozha.

Two years later at Kulikovo Field (not far from Tula), the troops of Prince Dmitry Ivanovich of Moscow encountered Mamai himself. “And the battle was fierce and mighty and the fighting savage and the din fearsome; ever since the creation of the world, the Russian grand princes had not had to fight such a battle…” according to the ‘Chronicle Tale’ about the battle. “When they fought from the sixth hour to the ninth, the blood of the Russian sons and that of the pagans poured like rain from a thundercloud and a countless number fell dead on both sides. And many men of Rus’ were overcome by the Tatars and the Tatars by the men of Rus’. And corpse fell on corpse, Tatar body on Christian body; here a Rusin could be seen in pursuit of a Tatar and there, a Tatar pursuing a Rusin.”

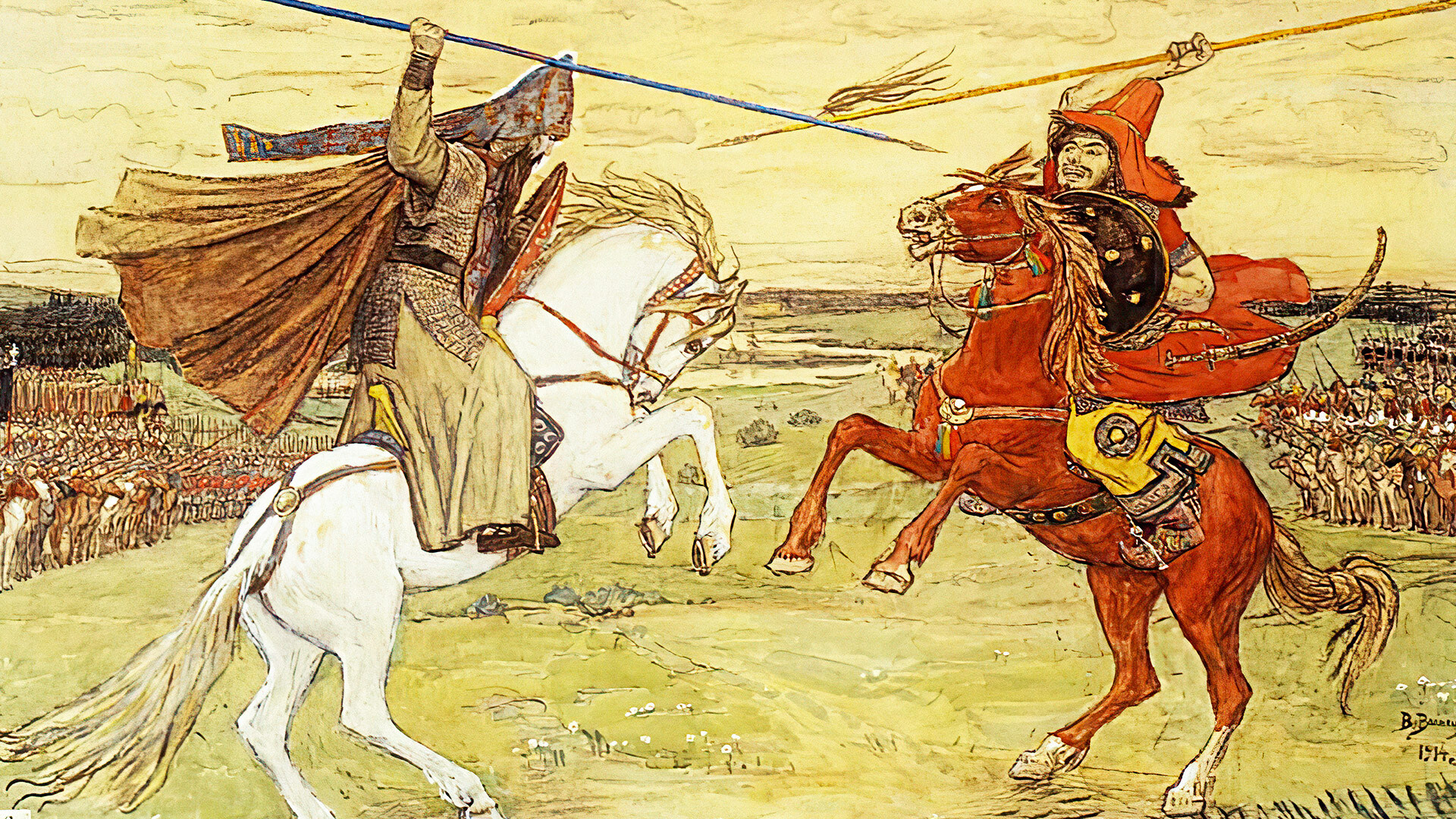

Duel between Peresvet and Chelubey on the Kulikovo field.

Duel between Peresvet and Chelubey on the Kulikovo field.

The outcome of the battle was decided by a Russian ambush force that struck the rear of the attacking Mongol horsemen. Losing almost his entire army, Mamai fled and was shortly conclusively finished off by his main rival, Khan Tokhtamysh, who, unlike the usurper Mamai, was a descendant of Genghis Khan and was regarded as the legitimate ruler of the Horde. Having ended the ‘Great Strife’, Tokhtamysh succeeded in burning down Moscow in 1382 and forcing the resumption of tribute payments. Nevertheless, the process of liberating Rus’ from the invaders that was set in motion after the triumph at Kulikovo Field was now unstoppable.

Siege of Moscow by Tokhtamysh.

Siege of Moscow by Tokhtamysh.

The Russian princes no longer regarded the Mongols with fear and trepidation. They frequently flouted the payment of tribute with little concern about the reaction from the Golden Horde, which, besides, was to fall apart by the beginning of the 15th century under the onslaught of the Central Asian conqueror Tamerlane. The final attempts to bring the Russians to submission were undertaken by Akhmat Khan, who ruled the so-called Great Horde, the largest of the fragments of the once-mighty state.

Defense of Moscow from the Khan Tohtamish.

Defense of Moscow from the Khan Tohtamish.

In 1472, a Mongol army attempted to reach Moscow, but was stopped on the River Oka near Aleksin. A new campaign was mounted eight years later. The two sides met on the River Ugra and, after several unsuccessful attempts at a forced crossing, Akhmat withdrew his troops. Mongol power in Rus’ was finally over.

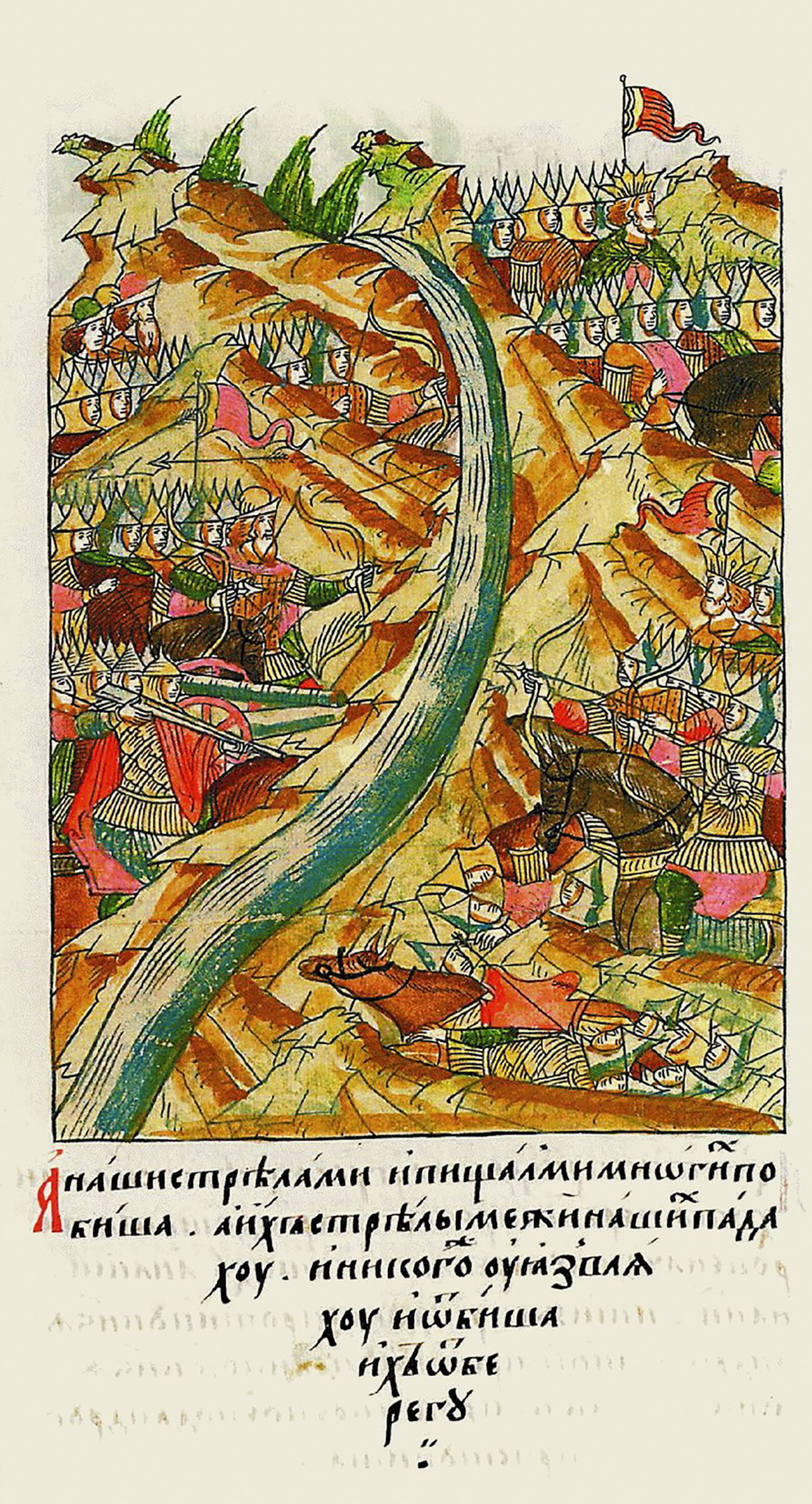

Standing on the Ugra River,

Standing on the Ugra River,