The first ban on Christmas trees was enacted back in Tsarist Russia: after the start of World War I, it was decided to part ways with everything German, including the tradition of decorating a conifer for Christmas and New Year’s. After seizing power in 1917, the Bolsheviks reinstated the celebration and even arranged New Year’s parties for children. But in 1929 a new ban was introduced – from Stalin this time.

The new Soviet rule didn’t have anything against the return of Christmas trees and New Year’s celebrations after the tsarist bans - especially as a symbol of equality (before the Revolution, Christmas trees were a privilege of the wealthy). On the contrary, the authorities encouraged it: Vladimir Lenin himself took part in children’s New Year’s parties. In 1919 he visited a forest school in Moscow’s Sokolniki district, where the first New Year’s celebration with a Christmas tree for kids was arranged. His secretary, Vladimir Bonch-Bruyevich, remembered the children’s meeting with the leader of the world proletariat like this: “They took him from the adults. Dragged him away to drink tea, eat treats, gave him jam… And he gave them nuts, poured them tea, watched everyone closely, as though all of them were his family… Nothing could have been done about the kids. They captivated Vladimir Ilyich completely.”

Sokolniki park museum.

This leniency didn’t last, however. After Lenin’s death in 1924, attempts were made to turn Christmas into a communist holiday. Accusatory reports were read during the holiday to expose the economic background of the “bourgeois, religious” Christmas and New Year’s; performances and political plays were staged. Later, the Komsomol [the All-Union Leninist Young Communist League] version of Christmas was criticized as well – for its ineffectiveness in battling religion – and in 1927 Stalin gave a speech, in which he pointed out the flaws in the Communist Party’s work: “We also have another fault, the weakening of the anti-religious struggle.” And so, the struggle intensified: in 1929 the government published a decree, stipulating that Christmas and New Year’s were declared working days and were not considered holidays anymore. Cutting down and selling of conifer trees was also prohibited – volunteers were tasked with monitoring compliance with the new law, going from one apartment to the next to check if a Christmas tree was being put up in secret. Soviet writer Irina Tokmakova remembered: “The glorious holiday of Christmas was banned, and those who dared to celebrate it could pay with their job or even their freedom...”

Antichristmas children demonstration, 1929. Banner on the left says 'Parents, don't confuse us - don't organize Christmas celebration'; on the right: 'Raise your kids with the help of a teacher, not God'.

Public domainNevertheless , families loyal to traditions continued to celebrate Christmas and New Year’s despite the ban.

For six years the country celebrated New Year’s and Christmas clandestinely, afraid of the volunteer checks and neighbors’ denunciations. However, in 1935, a letter from party member and Stalin friend, Pavel Postyshev, was published in the Pravda newspaper, calling for ta New Year’s celebration for kids to be arranged: “At schools, orphanages, Pioneer’s Palaces…there should be a Christmas tree for kids everywhere! There should be no kolkhoz [collective farm] where the administration and Komsomol members didn’t arrange a Christmas tree party for their kids on New Year’s Eve.”

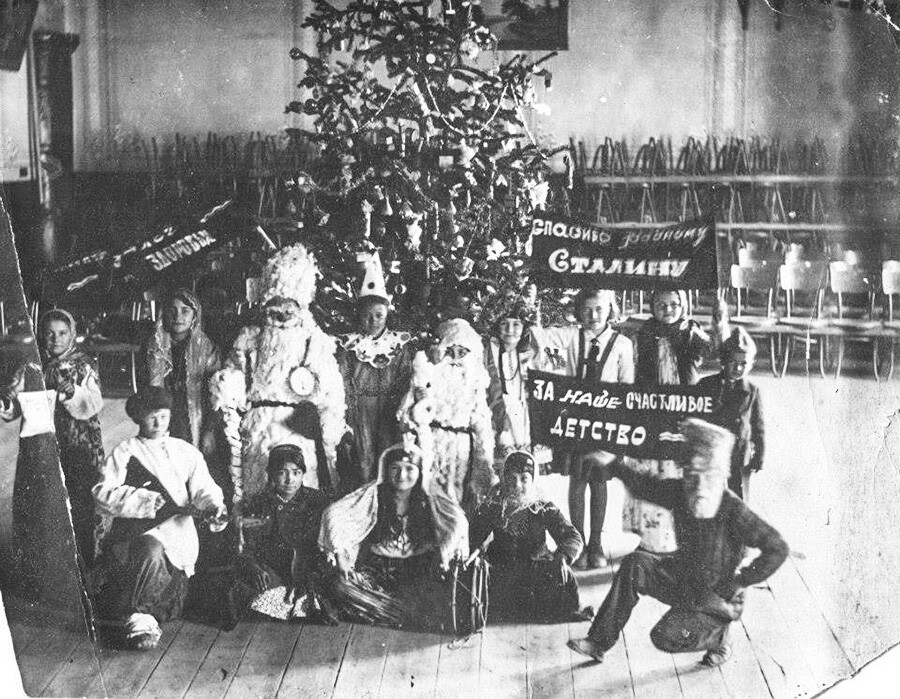

First legal New Year's celebration with a decorated tree in Namangana, Uzbek Repubic, 1936.

Unknown author/russiainphoto.ruThe letter, of course, happened with Stalin’s permission: Secretary General Nikita Khrushchev described in his memoirs how Postyshev raised the matter of bringing back the New Year’s celebration in a private conversation with Stalin. The latter replied: “Take initiative, publish a proposal in the press to give children back their Christmas tree, and we’ll support it.” It’s still unclear why Stalin made such a decision. But what had recently been banned was now compulsory – Christmas tree parties for schoolchildren and kindergartners were to be arranged even in the most remote corners of the country.

Postyshev’s initiative transformed a Christmas tradition into a New Year’s one – before the Revolution, the Christmas tree was a symbol exclusively of Christmas, but the USSR’s struggle against religion changed all that.

The New Year's celebration in the column hall of The House of the Unions, 1948.

Сергей Васин/МАММ/МДФIn 1937 the first Kremlin yolka – or “Christmas tree party” - took place. It was to become the main children’s party of the entire country. And it was a great honor to be invited. Among the guests were distinguished pioneers [the Soviet version of Boy or Girl Scouts], high-achieving students and children of leading industrial workers and the political establishment. There, Snegurochka, the granddaughter of Ded Moroz (Russian Santa Claus), appeared for the first time – and has been a necessary part of Russian children’s New Year’s celebration ever since.

Moscow, USSR. Children, Ded Moroz (Father Frost) and Snegurka (Snow Maiden) dance as they take part in the New Year celebrations in the Kremlin Palace of Congresses.

Nikolai Malyshev, Valery Khristoforov/TASSDear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox