Russia had its own savage GOLD RUSH before America

Murder in Siberia

In 1827 a rumor reached two rich Russian merchants from the Urals – Andrei and Fyodor Popov – that somewhere in Siberia a peasant and an Old Believer named Egor Lesnoy found gold somewhere near the Dry Berikul River in Tomsk Province in Siberia.

The merchants sent their envoy to meet Lesnoy but the envoy failed to extract information about the gold’s whereabouts. Then, Popov decided to personally make the man an offer he could not refuse. They came to Lesnoy but found out that the man was strangled to death sometime before.

The merchants did not give up and pursued Lesnoy’s stepdaughter to show them where the man used to go when he was alive. The girl agreed and showed the merchants where her deceased stepfather used to dig the earth. Examining his work, the Popov merchants realized there was gold in Siberia.

Thus began the history of the gold rush in Russia.

Gold rush

By that time, the Russian government had already sanctioned private efforts to mine gold in all regions of the vast empire. A Senate decree issued in 1812 gave all Russian subjects the right to search and mine gold and silver ores if they paid taxes to the treasury. Depending on the region and decade, the tax varied from five to up to 40 percent of total production.

Gold-bearing sand washing. Photo by Prokudin-Gorsky, Ural, Beryozovsky District, early 20th century.

Gold-bearing sand washing. Photo by Prokudin-Gorsky, Ural, Beryozovsky District, early 20th century.

A few months following Andrei and Fyodor Popov’s discovery, the merchants explored the land near the tributaries and funded numerous mines there. In the first year of operation, they extracted roughly a pood (the traditional Russian unit of measurement - approx. 16.38 kilograms) of gold, then four the next year, sixteen the year after, and so on. Production grew exponentially and rumors of the rich Siberian soil spread throughout the Russian Empire.

Major Russian industrialists and merchants rushed to Siberia as well as myriads of poor daredevils who dreamed big. The Siberian gold rush began.

Filthy rich

In the golden decades of the Siberian gold rush that lasted from the early 1830s until the 1850s, the major players made fortunes mining gold in Siberia.

Prospectors at Sakhalin gold-bearing sand washing.

Prospectors at Sakhalin gold-bearing sand washing.

Earning big money fast, some of the merchants received a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to make their most ludicrous dreams come true. Then, hell broke loose.

One of the successful miners named Nikolai Myasnikov is said to have made his business cards from pure gold. A former serf named Tit Zotov who made a fortune from mining gold is said to have celebrated his son's wedding for an entire year. During the wild festivities, champagne was in such abundance that people used it to wash horses and fill bathtubs for maidens.

Another miner named Gavrila Masharov ordered the medal to be cast in solid gold weighing over eight kilograms so that he would award himself the title of the “emperor of all taiga.” As if this was not a big enough whim, Masharov would order his silk underwear to be sent to Parisian laundries for washing in spite of the fact that he had never been to France himself.

Gold-bearing sand mining on the Beryozovka River. Photo by Prokudin-Gorsky. Urals, District of the city of Beryozovsky, early twentieth century.

Gold-bearing sand mining on the Beryozovka River. Photo by Prokudin-Gorsky. Urals, District of the city of Beryozovsky, early twentieth century.

By 1836, Masharov had a lavish mansion built in taiga where he spent time in glass galleries and a greenhouse where pineapples grew. However, the eccentric lifestyle ended as abruptly as it began when Masharov was declared bankrupt as he was not able to pay his numerous creditors.

Hell on earth

For regular workers recruited from different corners of the Russian Empire, life in the mines was characterized by inhuman conditions.

Mining companies recruited a vast number of people by offering them a salary many times higher than what an average factory worker earned in Moscow. Moreover, every person who agreed to go to Siberia to work for mining companies received an advance of 135 rubles which amounted to half a year's wages for a worker in Moscow.

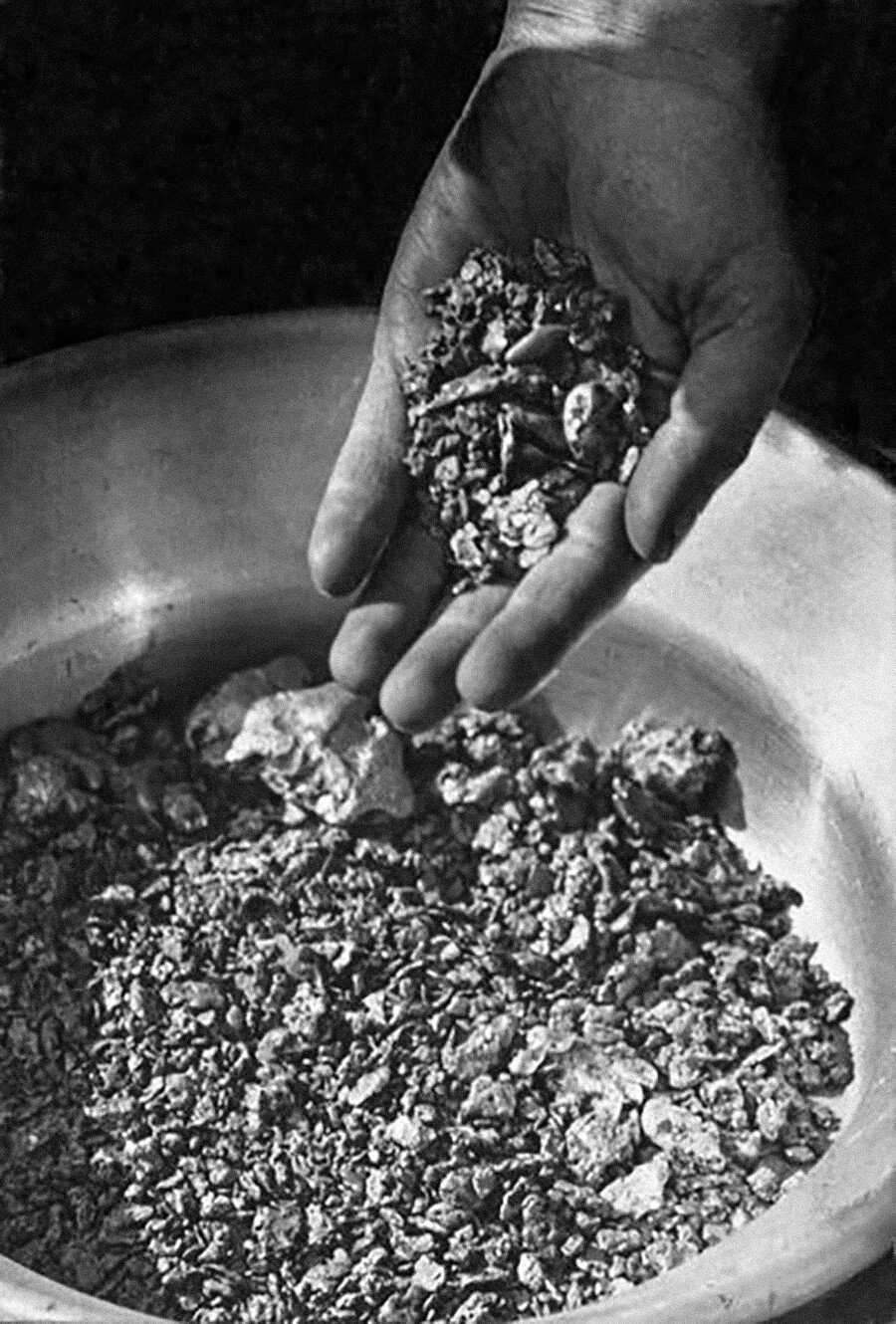

Washing gold by miners from waste dumps.

Washing gold by miners from waste dumps.

People rushed to the mines but the reality was far too grim for most of them. They worked for 12 hours a day and rested in cold and overcrowded barracks. In winter, workers operated knee-deep in water as bonfires were used to melt the frozen soil and rock formations. Having to walk for several kilometers to barracks in wet clothes and in freezing temperatures after another shift caused pervasive sickness and death.

In February 1912, a massive workers' strike broke out in the mines triggered by some of the workers having been served rotten meat for lunch. By March 1912, the number of protesters grew to up to 6.000 people. Workers demanded better living conditions, better food, increased salaries, a shorter workday, and the dismissal of 25 employees of the administration of the mines among other things.

The protests ended in a tragedy that would shock the whole Russian Empire. On April 17, 1912, soldiers opened fire on the workers killing, by different accounts, 150 -250 people. A photograph of the massacre was leaked to the press and reached St. Petersburg, triggering a government investigation, as well as massive protests throughout the country.

Victims of the Lena execution (apparently, the photos were taken by the station master of the Gromovsky mines, seized by Rt. Treshchenko, but were preserved and went to press).

Victims of the Lena execution (apparently, the photos were taken by the station master of the Gromovsky mines, seized by Rt. Treshchenko, but were preserved and went to press).

After the Russian Revolution and the Civil War, the new Soviet government monopolized gold mining in the 1930s, ending the years of the Russian gold rush forever.