In the 1920s, “free love” reigned in the USSR - pre-Revolutionary prohibitions and restrictions became a thing of the past. Along with the Socialist revolution came the sexual one. But, none of its proponents had any inkling of what would become of it in the 1930s.

The October Revolution led not just to a change of power, but also to a radical shift in culture and this affected relations between the sexes, too. In Tsarist Russia, extramarital relationships, whether premarital or adulterous, had been considered sinful and were condemned by society, as was divorce. But, while for men, such behavior had been quite acceptable, albeit frowned upon, a woman in such a situation would be labeled a ‘fallen woman’, which would permanently exclude her from society. A marriage was concluded in church, it was difficult to have it dissolved and the process was always damaging to the reputation of the individuals concerned.

When the Bolsheviks came to power, many moral and legal obstacles that had existed in relations between the sexes before the Revolution disappeared.

With the abolition of religion, marriage lost its sacred nature, became exclusively secular and it was easy to enter into marriage or dissolve a marriage an infinite number of times. Also, non-marital relationships were no longer regarded as reprehensible.

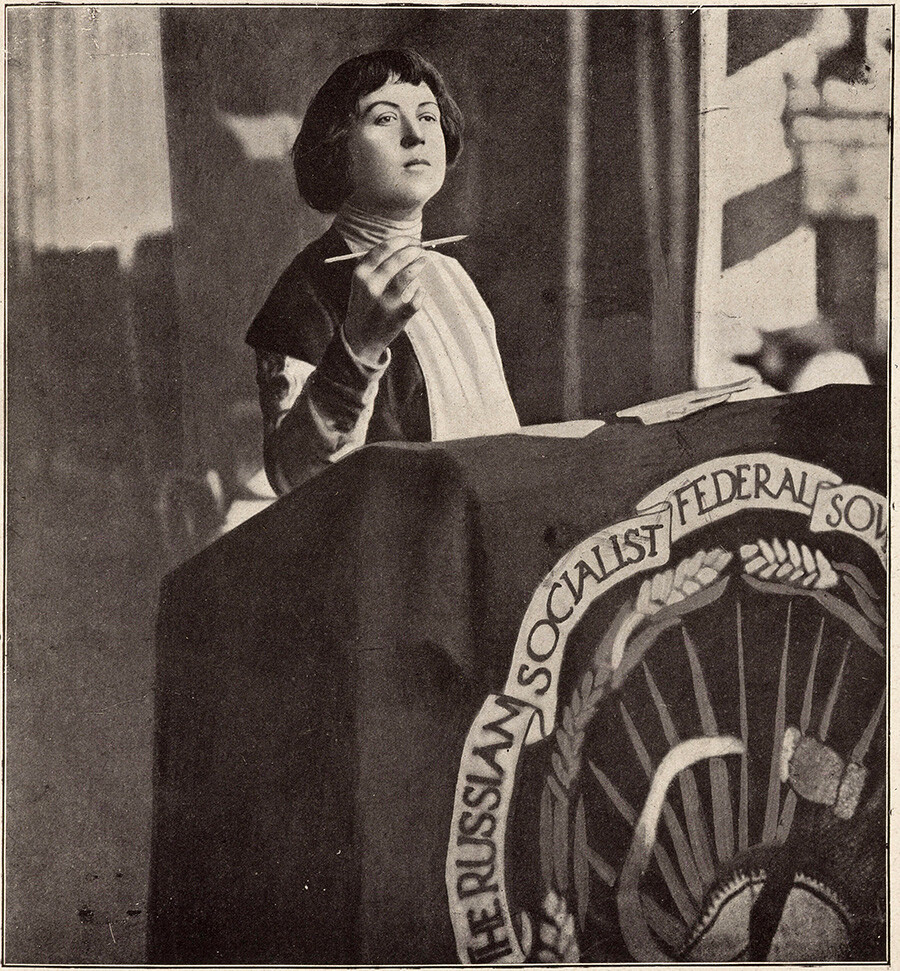

The Bolsheviks insisted that it was necessary to eradicate oppression, inequality and exploitation in not only societal, but also amorous relationships and that relations between the sexes must be based on mutual love and comradeship. “The task of proletarian ideology is not to banish Eros from social intercourse, but merely to replenish his quiver with arrows of a new paradigm, to cultivate a feeling of love between the sexes in the spirit of the greatest new psychic force - comradely solidarity,” Alexandra Kollontai, one of the main ideologists of women's rights in the USSR, once wrote on the subject.

Alexandra Kollontai, 1920.

Legion MediaIntoxicated with freedom, people didn’t delve into complex theoretical considerations and treated the change in morality as a sexual revolution. Party leaders themselves were often not blameless in this respect. According to some historians, Lenin had an affair with Inessa Armand, a colleague of Kollontai’s on women's rights issues. The latter was credited with having many lovers, as were other party leaders, such as Nikolai Bukharin and Anatoly Lunacharsky, who would themselves later become proponents of “the fight against sexual promiscuity”. The celebrities of the time embraced the trend: Vladimir Mayakovsky, the Revolution’s poetic icon, lived with married couple Lilya and Osip Brik, while another poet, Sergei Yesenin, was married three times - on top of his relationships outside marriage.

Mayakovsky with Lilya and Osip Brik.

Public domainThe change in morals among young people was borne out by statistics: In 1922, a survey was conducted among students at one of the Moscow higher educational establishments about their sexual relations. The percentage of girls who were sexually experienced at the time of the survey had increased from 25.7 percent (in 1914) to 53 percent. Admittedly, for men the difference was not as striking: The figure rose from 67 percent (in 1914) to 85.5 percent.

Far from all party leaders supported the idea of free love and the new family policy. But even those who weren’t initially put off by it were rapidly disabused of its attractions. Young people’s behavior in the 1920s only reinforced their negative impression of moral license. In her book ‘Reminiscences of Lenin’, revolutionary figure Clara Zetkin cited the Bolshevik leader’s views on the subject: “Young people’s changed attitudes to matters to do with sex is, of course, ‘principled’ and is alleged to be based on theory. Many describe their stance as ‘revolutionary’ and ‘communist’. […] None of this has anything to do with free love as we, communists, understand it. You will know, of course, the famous theory that in a communist society the satisfaction of sexual urges and amorous desires is as straightforward and insignificant as drinking a glass of water. […] Its proponents claim it to be a Marxist theory. No thanks to this kind of Marxism that exclusively derives all phenomena and changes in society’s ideological superstructure directly, linearly and totally from its economic underpinning alone. Things are far from being that simple.

[…] But, are we to believe that a normal person in normal conditions will lie in the street in the mud and drink from a puddle? Or even from a glass to whose rim dozens of mouths have been pressed? But, most important of all, is the societal aspect. Drinking water is indeed an individual matter. But, when it comes to love, two people are involved and out of this, a third, new life emerges. Here lies the societal interest, from whence a duty to the collective emerges.”

Vladimir Lenin with his wife Nadezhda Krupskaya.

Color by Klimbim 0.1The late 1920s saw the start of a return to a more conservative view of relations between men and women. In 1926, People’s Commissar for Education Anatoly Lunacharsky presented a report titled ‘O byte’ (‘About Everyday Life’) in which he criticized young people’s attitudes to sex: “…love should not be casual, a ‘glass of water’, but it should be raised to a rightfully high level, to something extremely meaningful. This was the rarefied love Engels was referring to in his book on the family and the state; the sort of love in which a man says: I love this woman and no other, with her I can construct my happiness, I shall make the greatest sacrifices for her, I can only be happy with her. It is when a woman says: I love this man, he is my choice - this is when love is not mundane or debauched.” In the same year, Nikolai Bukharin, a member of the Central Committee, one of the most important party bodies, delivered the speech, ‘Borba za kadry’ (‘The Struggle for Cadres’), in which he called for a moral code to be drawn up for the Komsomol and for a special struggle to be waged against “sexual license”.

The sexual freedom of the 1920s was becoming dangerous for the state. Abortions had been legal since 1920 and they were carried out without charge, something that led to a steep increase in their prevalence. The institution of marriage and motherhood was also breaking down: when a pregnancy could not be terminated, a woman could place a child in a children’s home, but these were already overcrowded. The USSR was waging a difficult battle against child homelessness: wars, revolutions and economic crises had led to an orphanage population of around half a million children by 1922. Others ended up in the streets and turned to crime.

Orphans of Samara region, 1920s.

Public domainAuthorities began tightening up the system with moral censure: After speeches by senior party officials condemning promiscuity, local authority and self-government bodies stepped in. Private life became a public matter - if someone behaved improperly in the opinion of his or her colleagues or bosses or, if the latter learned of discord in the family, the case was submitted to a public meeting at the wrongdoer’s place of work or in party organizations. At the meeting, the participants would attempt to “talk sense” into the individual who had strayed from the straight and narrow or try to make peace between the spouses. Almost anything could result in a public discussion of this kind: unfaithfulness, rows or simply “frivolous” behavior. For instance, at a Leningrad factory in 1935, a young fitter was expelled from the Komsomol for “going out with two women at the same time” and a female worker was issued with a reprimand for her “excessive preoccupation with dancing and flirting”. Any manifestation of immorality could entail expulsion from the party, prompting party members, whose lives were conducted in the public eye, to be particularly cautious in choosing their significant other.

Soviet poster, the inscription says: 'Children are the joy of a soviet family, the future of our country'.

Public domainFurthermore, the registration of a divorce was made a very expensive procedure and the fee increased many times over for successive divorces. In the post-war years, alongside ads for new theater productions and circus performances, the back pages of newspapers carried a separate column with divorce announcements: “Comrade Potapov Mikhail Petrovich, resident at [...] is instituting divorce proceedings against Comrade Potapova Mariya Pavlovna, resident at [...]. The case is to be heard by the People’s Court.”

Aleksei Pavlovich Solodvnikov The divorce, 1955.

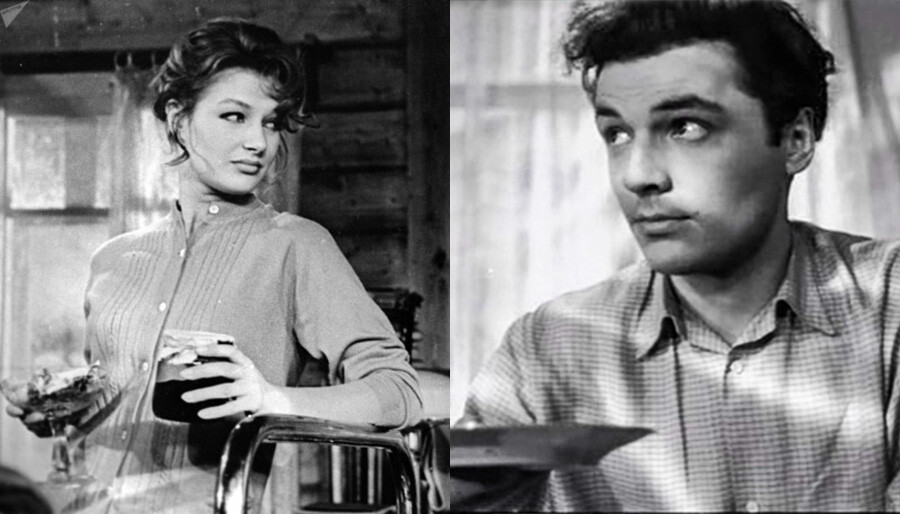

MutualArtPopular culture also affirmed the new norms of private life. In movies, protagonists who failed to show constancy in their intimate relationships were depicted either as negative characters, like the double-dealer and rapist Mark in the famous movie ‘The Cranes Are Flying’ (1957) or as characters whom no-one likes because they have ugly natures, despite their physical attractiveness, such as the good-looking Anfisa in the cult movie ‘The Girls’ (1962).

Anfisa from the movie 'The Girls' and Mark from the movie 'The Cranes Are Flying'.

Yuri Chulyukin/Mosfilm,1962; Mikhail Kalatozov/Mosfilm, 1957A fee had to be paid for abortions from the early 1930s onwards, although this was not announced in the media. Abortions were then completely banned in 1936, except when there were serious medical grounds to the contrary (the ban was lifted in 1955, because the large number of back-street abortions were costing women their health and even their lives).

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox