Grand Duke Michael Romanov

Public domain, color by KlimbimMichael was not interested in politics. He liked women and automobiles. He was handsome, courageous, rich, well-educated and, at the same time, unassuming. He had every right to the Russian throne, but voluntarily gave it up. He was Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich Romanov, the youngest brother of Nicholas II.

Nicholas was Alexander III’s eldest son and ascended the throne after his father’s death. Michael was the fourth son and so distant in line to the throne that he never really expected to occupy it. But, Nicholas II didn’t have a male heir for a long time and his and Michael’s middle brothers had died. And, in accordance with the law of succession, Michael ended up next in line to the throne.

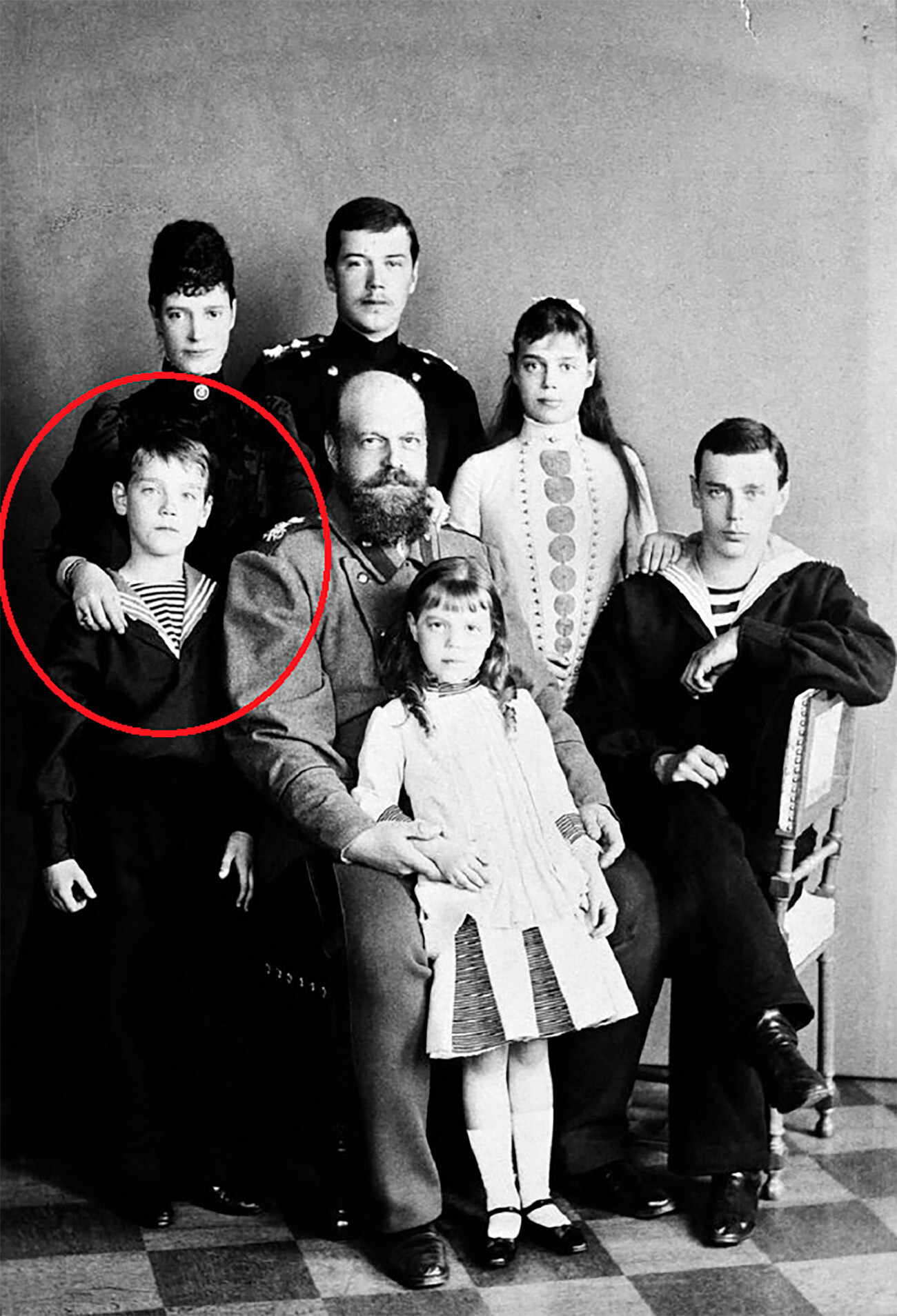

Alexander III with his children

Public domainUntil 1904, when Nicholas’ long-awaited son, Alexei, was born, Michael had been heir presumptive. But, even after the birth of Alexei, Michael was entitled to act as regent for his nephew, had the emperor died before his son came of age. And, bearing in mind Alexei’s poor health, Michael had every chance of inheriting the crown of the Russian Empire.

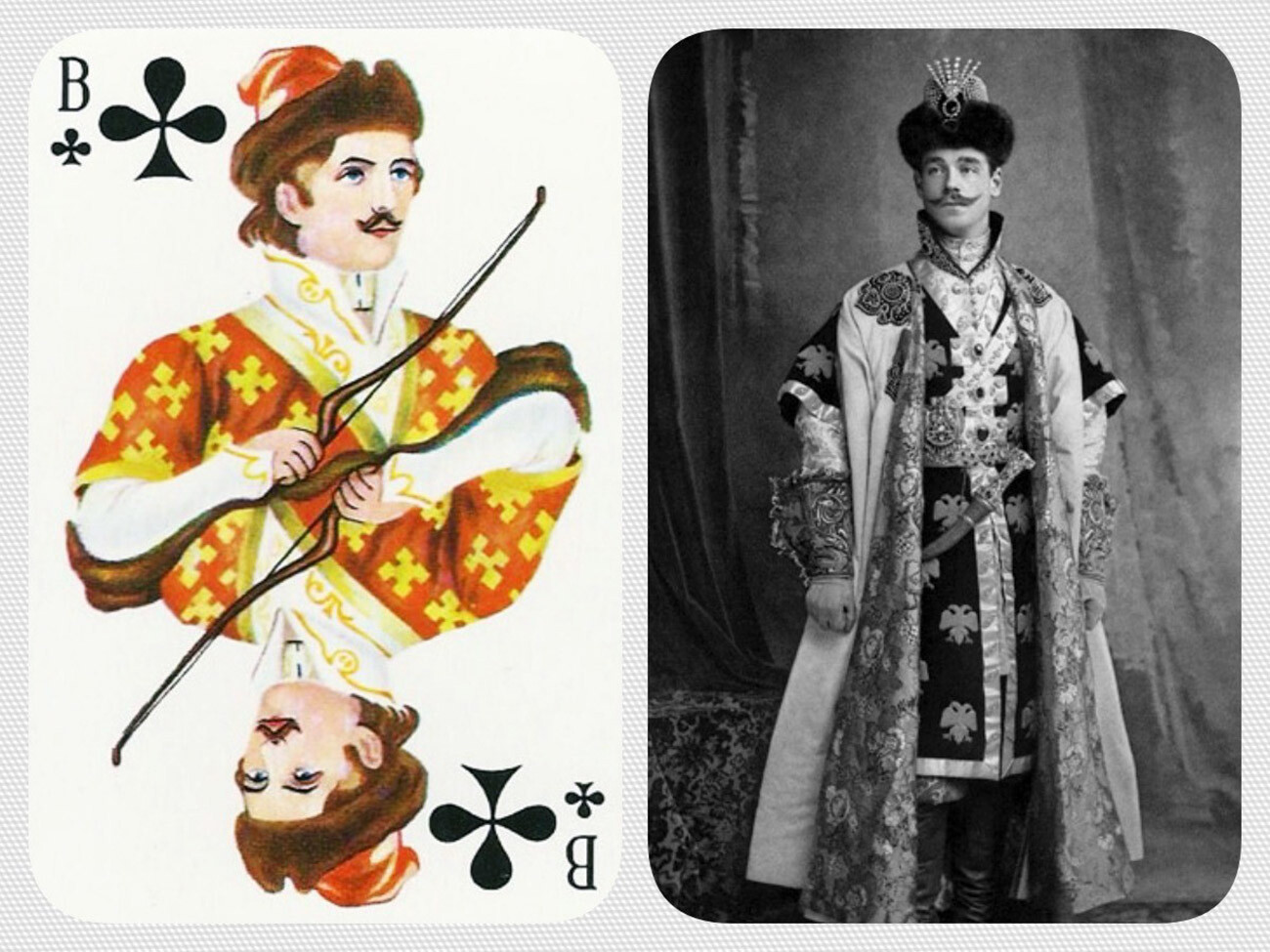

The image of Michael at a 1903 costume ball was used as the prototype of the Jack of Clubs in the famous “Russian Style” pack of playing cards.

Public domainIn some ways, Michael Romanov can be compared to British King Edward VIII (and even Prince Harry). What they have in common is their love for women who were absolutely unsuitable for them by social status and were not related to any royal family.

Michael fell in love with Natalia Sheremetyevskaya, the daughter of a Moscow lawyer. What is more, she was twice married and had a daughter. At the ball where they met, the Grand Duke disregarded decorum and asked her to dance the mazurka with him and then, according to rumors, they left the soirée together.

Grand Duke Michael Romanov

Public domainNicholas was against his brother’s liaison, but Michael chose love. He was said to be of a mild disposition, but, in matters of honor, he was extremely principled - he could not insult the woman he loved with the status of mistress. In 1910, they had a son, whom they named George, and, two years later, the couple married in a church in Vienna.

Michael Romanov and Natalya

Public domainNicholas was furious and wrote to his mother that he was severing all ties with his brother. Michael was stripped of all of his ranks and even forbidden to return to Russia. It goes without saying that he lost all his rights to the throne, too.

At the outbreak of World War I, Michael, as a man of honor, asked Nicholas for permission to return and fight for Russia. After getting the Imperial go-ahead, the Grand Duke commanded the so-called ‘Savage Division’, made up of Caucasian Moslem volunteers who could not fight in official units.

Michael as Commander of the ‘Savage Division’ with Natalya

Public domainMichael’s wife Natalia accompanied her husband everywhere and, as was the custom of female members of the tsarist family, performed charity work and organized military hospitals for the wounded. Michael also made his St. Petersburg mansion available for the needs of the Red Cross. Nicholas II softened his stance, recognized both his brother’s marriage and his nephew and granted Natalia the title of Countess Brasova.

In March 1917, during the events of the Revolution, Nicholas II signed a document of abdication on his own behalf and that of his underage son Alexei - in favor of his brother Michael. The now-former tsar sent his brother a telegram, in which he addressed him as ‘Michael II’ and expressed the aspiration that he would succeed in saving the Motherland. “The events of recent days have compelled me to decide irrevocably on this extreme measure. Forgive me if I have aggrieved you and for not managing to warn you in advance,” Nicholas II wrote.

Shocked by his brother’s abdication, Michael realized that his own position was even weaker. He understood that his ascending the throne could provoke further revolutionary turmoil. The popular anger seemed to him to be directed at the monarchy as a whole.

Ilya Repin. A sketch portrait of Michael for the painting 'Ceremonial Sitting of the State Council on 7 May 1901 Marking the Centenary of its Foundation'

Public domainAnd, although some military units had already managed to swear allegiance to Michael, he signed a “temporary” renunciation of the throne - permitting, as it were, the people themselves to choose their destiny in a vote. In the document, he also called on citizens to submit to the authority of the Provisional Government.

Less than 24 hours passed between Nicholas II’s abdication and Michael’s signing of his own renunciation of the throne and historians argue to this day whether he can be regarded as having been ‘Emperor of All the Russias Michael II’ in that brief time. Arguments against this theory are put forward by proponents of the view that the documents were unlawful and Michael had lost any claim to the throne back in 1912, when he contracted his morganatic marriage.

After the Revolution, Michael was unable to avoid the fate that awaited many members of the tsar’s family. He spent a year under virtual house arrest at his property in Gatchina outside St. Petersburg (then Petrograd). In March 1918, he was arrested by the Bolsheviks and sent into exile in Perm.

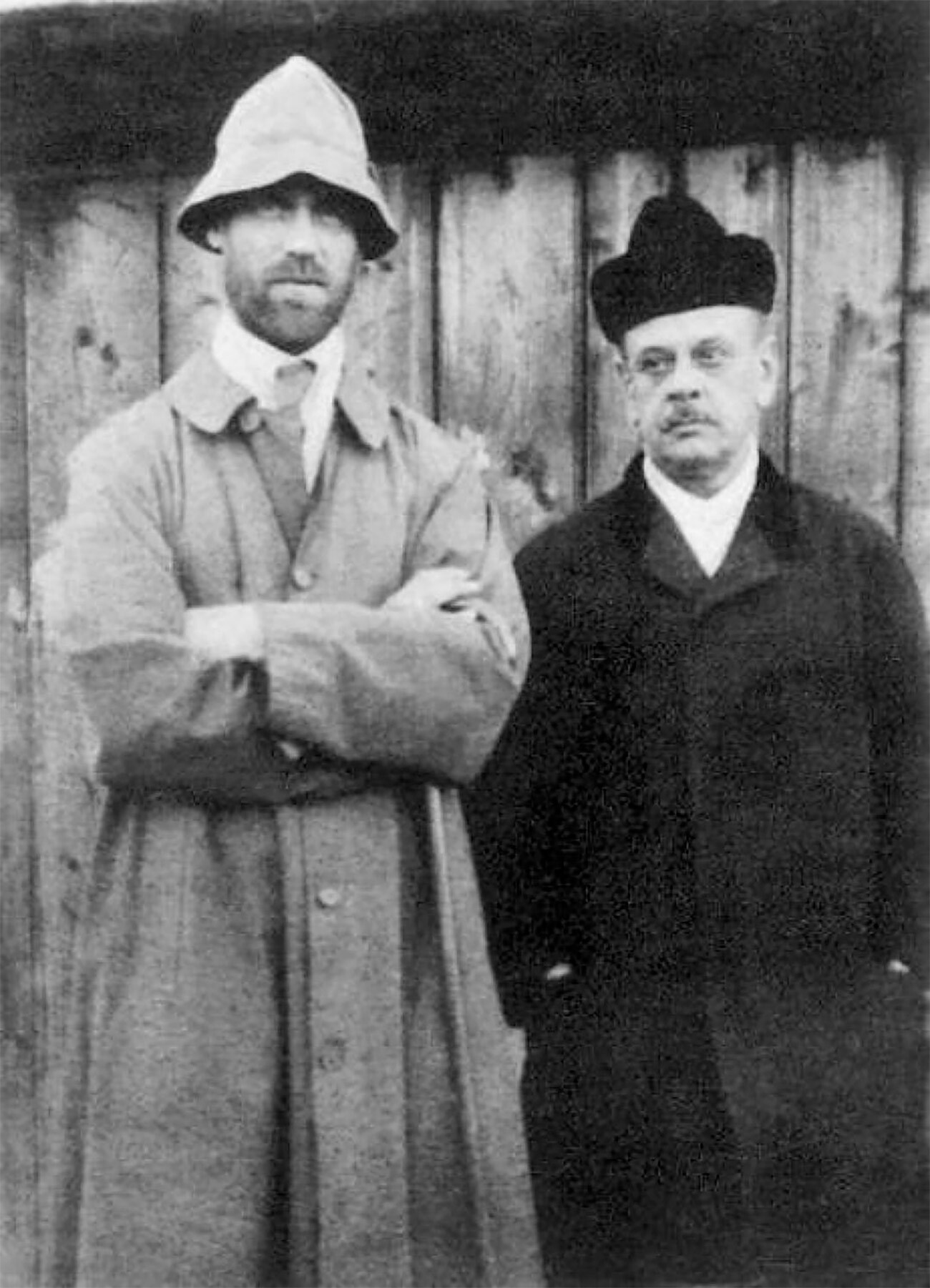

‘The Prisoner of Perm’, Michael (left), 1918

Public domainHis wife Natalia stayed on in St. Petersburg (Petrograd) and did her best to secure his return, but without success. In June, she received a telegram that Michael had disappeared. Most likely, he was abducted by the Bolsheviks at night, along with his secretary, and secretly taken to a forest and murdered. Although Perm authorities have long denied it, insisting he was kidnapped by unknown people. The actual murder was hushed up for a long time and his remains were never found.

Natalia, who had briefly visited him in Perm, managed to flee Russia on forged papers. She died alone and in poverty in Paris in 1952.

Their son George had been smuggled abroad immediately after the Revolution. He went to school in England and continued his education in France. He inherited a sizable legacy from his grandmother, the Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna. But the 20-year-old young man died in a road accident in 1931.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox